America 250: How immigrants brought opera to American shores

To commemorate the 250th anniversary of the signing of the Declaration of Independence, Opera America Magazine is exploring the roots of American opera in a series of essays by renowned cultural historians, artists, and field leaders.

This series is made possible in part thanks to generous support from Melanie Wyler.

The Vienna-born, New York-raised soprano Emma Juch made a splash when she toured the United States in the 1880s. According to the British-born critic Alan Dale, her performances evinced a “joyous star-spangled bannerism,” proving that American opera was on the rise. “The days when the divine but dollaresque Patti can float over to American shores and demand five thousand for a single warble are surely passing away,” Dale predicted, dismissing the famed Italian singer Adelina Patti as a relic of a Eurocentric past. “American singers will soon be recognized all over the world, and even in their own country, I believe.”

Juch benefited from an American cultural landscape in which opera played a prominent role. By the end of the 19th century, opera was firmly established within American culture, beloved by a wide range of people within and beyond the opera house. When the American lawyer and writer George Makepeace Towle returned from a stint in England in the 1860s, he was pleasantly surprised to discover that back in his home country, opera was easy to find. “Lucretia Borgia and Faust, The Barber of Seville, and Don Giovanni are everywhere popular,” he reported. “You may hear their airs in the drawing room and concert halls, as well as whistled by the street boys and ground out on the hand organs.”

These writers offer us glimpses of an exciting past: an America where opera stood as a valuable, vital part of popular culture. But who made it so? To answer this question, music historians have pored through scores and libretti, newspapers and diaries, published books and unpublished letters. Building on the important work of cultural historian Lawrence Levine — one of the first to show how important opera was to the developing nation — a new generation of scholars has found compelling evidence of how opera flourished within many different American communities during its early years in the United States.

The Great Wave

This development coincided with, and was shaped by, the United States’ changing population. In the earliest years of the nation’s existence, the populace consisted largely of English and Scots-Irish settlers, as well as enslaved Africans who were forced to come to the U.S. under the brutal system of chattel slavery. As immigration continued to transform the young nation during the 19th and early 20th centuries, opera also changed: New Americans made the art form into both popular entertainment and a shared form of public culture.

Opera’s American roots run deep. The art form had a scattered presence in the colonial era; in 1736, a performance of the British ballad opera Flora in Charleston, South Carolina, marked the first presentation of an opera on the North American continent. Ballad operas, an English genre in which songs and dances are interspersed with comic, often satirical dialogue, remained popular in the decades that followed. The most notable of these was The Beggar’s Opera, with a libretto by John Gay and musical arrangements by Johann Christoph Pepusch, which satirized Italian opera traditions in part. These performances often took place in taverns or other gathering places, bringing opera to places where Americans already congregated.

But it was in the 19th century that opera really began to flourish. The United States’ population exploded during these years, thanks to the arrival of additional waves of immigrants. Between 1840 and 1890, an estimated 14 million people immigrated to the United States, mostly from Britain, Ireland, and Germany. Another 18 million followed between 1890 and 1920, most hailing from Eastern and Southern Europe.

Music of the Storm

In parallel, new forms of art and entertainment sprang up. Evening-length variety programs became a staple in growing towns and cities, and opera appeared on these programs alongside parlor songs, dramatic readings, skits, and more. One New York City program by a group known as Perham’s Troupe, for instance, featured Don Giovanni alongside a selection of “jigs” and “fancy dances.” (The group also performed “Ethiopian songs,” demonstrating how operatic performance was often interwoven with the noxious, incredibly popular tradition of Blackface minstrelsy.) In a cultural world shaped by the forces of immigration, opera shared space easily with other types of art. As the writer and avid opera fan Walt Whitman put it in his 1869 poem “Proud Music of the Storm”:

All songs of current lands come sounding round me,

The German airs of friendship, wine and love,

Irish ballads, merry jigs and dances, English warbles,

Chansons of France, Scotch tunes, and o’er the rest,

Italia’s peerless compositions.

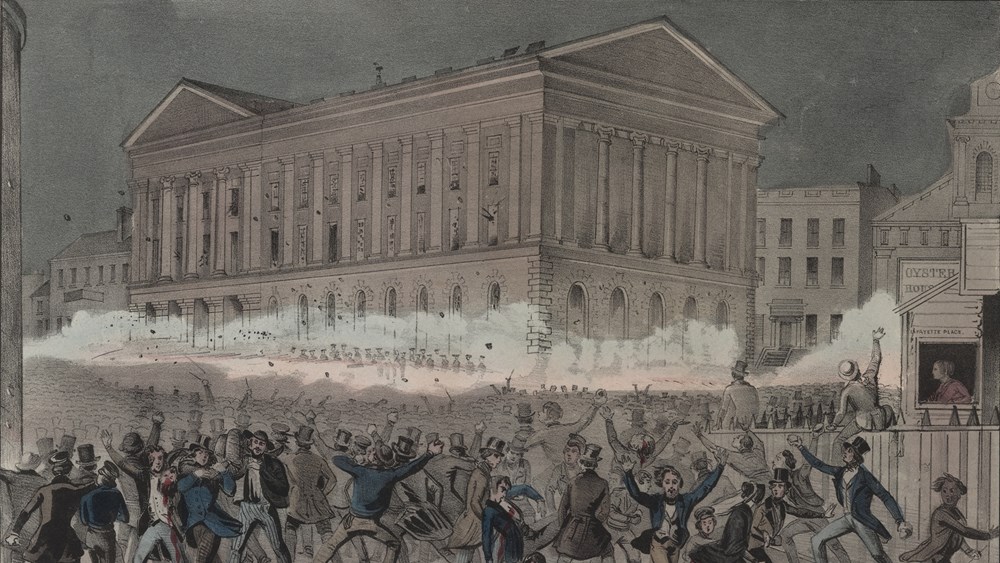

New York City played host to an embarrassment of operatic riches. Since the García family’s first performance of Italian opera in the city in 1825, New York had seen visits from an illustrious cast of European celebrity artists, as well as the establishment of opera houses: Palmo’s Opera House, Astor Place, the Academy of Music.

But the Big Apple wasn’t the only center of the American operatic universe. Local opera scenes began to crop up across the nation. New Orleans was a prime example. Beginning in 1819, the city’s Théâtre d’Orléans offered regular performances of operas, and even hosted the nation’s first resident opera troupe. It wasn’t easy: Such venues were “perpetually plagued by fire, disease, and the corresponding threat of low box office receipts,” in the words of music historian Charlotte Bentley. Against the odds, however, the theater managed to produce opera for several decades. The repertoire was primarily French, well-suited to a cosmopolitan city located in a former French colonial territory: Grand works like La muette de Portici (Daniel Auber, composer; Germain Delavigne and Eugène Scribe, librettists) and Les Huguenots (Giacomo Meyerbeer, composer; Eugène Scribe and Émile Deschamps, librettists) enjoyed ambitious productions.

The people who made the house run ranged from English-born impresario James Caldwell to the enslaved personnel, their names largely lost to history, who worked within the theater. Edmond Dédé, among the first Black American composers of opera, was also born in New Orleans in 1827, though his opera Morgiane wouldn’t see its world premiere until 2025, and he would emigrate to Europe in 1855.

Westward Ho!

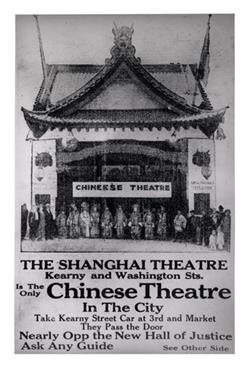

Thousands of miles away, Chinese immigrants in San Francisco developed a similarly robust culture of Cantonese opera beginning in the 1870s. Despite the xenophobic restrictions on immigration posed by the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882, they created plentiful venues for Cantonese opera. Located in the city’s Chinatown, these theaters drew audiences where Chinese American laundry workers brushed shoulders with tourists and non-Chinese locals. And the music they heard was profound, a place to reflect on identity and belonging in a diverse nation. It was opera, writes music historian Nancy Yunhwa Rao, that “gave voice to Chinese immigrants’ everyday stories of desires, regrets, laughter, and dreams.”

Opera was also on the go. The roads, rivers, and railroads that crisscrossed the expanding nation shuttled traveling opera troupes from town to town, city to city. Pre-Civil War America was awash in itinerant opera troupes: some that were organized around a single star performer, others that performed opera exclusively in Italian, and a third cohort that performed in English. Later in the 19th century, English-speaking troupes took on special significance. By the 1880s, one writer called English-language opera “another warble of American independence,” suggesting that the nation had stopped imitating Europe and achieved a unique cultural status.

Musicologists Katherine Preston and Kristen Turner have illuminated the careers of singers and companies who performed in English, such as the aforementioned Emma Juch and the enormously popular Emma Abbott Grand Opera Company. While these figures signaled the importance and popularity of opera within American culture, they also spoke to the cultural pressure imposed upon immigrants to assimilate: For instance, German and Italian immigrants who might once have enjoyed hearing opera in their native language were now compelled to attend more “Americanized” productions.

In the same era, the Black soprano Sissieretta Jones, a contemporary of Juch, blazed a pathway to stardom by touring the U.S. and abroad, becoming the highest-paid Black American performer of her day. American racism prevented Jones from joining existing opera troupes or pursuing a full career in the art form, however, and she eventually formed her own touring troupe, which featured opera alongside dance, comedy, and acrobatic acts.

Key changes

What happened to this freewheeling opera scene? There are a few ways to answer this question. One is to point to the establishment, during the Gilded Age, of major opera houses like the Met. By linking opera to wealthy patrons and elite audiences, these institutions weakened opera’s relationship to popular, democratic culture.

But another is to point out that opera never stopped being beloved by a wide range of Americans. Musicologist Larry Hamberlin has shown that early Tin Pan Alley songs — with titles like “That Opera Rag” and “My Cousin Caruso” — often gestured toward Americans’ love of opera; jazz musicians like Louis Armstrong improvised on snippets of Rigoletto and Pagliacci; radio and TV broadcasts of operatic performances proved enormously popular. Opera didn’t disappear from popular culture, but the rise of elite operatic institutions meant that its cultural associations with widespread popularity gradually faded away.

The eccentric, vibrant, slightly chaotic world of 19th-century opera won’t be replicated in our time, but it might nonetheless offer inspiration today. Most of the companies prevalent during the 19th century were more ephemeral endeavors, but several founded in their wake, some with immigrants at their helms, during the early part of the 20th century — such as Cincinnati Opera (1920), San Francisco Opera (1923), Central City Opera (1932), and the Florentine Opera (1933) — are still in existence. These modern companies, like the opera troupes of the 19th century, are working to meet people where they are, to welcome diverse audiences, and to create social spaces where people from different backgrounds might meet and mingle. Within and beyond these spaces, operatic music has retained its power to captivate listeners — to create experiences like Walt Whitman’s, in which “all songs of current lands come sounding.”

This article was published in the Winter 2026 issue of Opera America Magazine.

Lucy Caplan

Lucy Caplan is an assistant professor of music at Worcester Polytechnic Institute. She wrote Dreaming in Ensemble: How Black Artists Transformed American Opera (Harvard University Press, 2025).