My First Opera: Laura Kaminsky

I’ve always found the making of art to be fascinating. When I was a kid, growing up in Manhattan, my younger sisters and I would incorporate what we were learning at our various lessons — piano, guitar, dance — and weave them into a “variety show” that we’d put on for my parents on Saturday nights. What I liked most about these evenings was the producing, not the performing. I would stage a scene from Fiddler on the Roof or West Side Story, and my poor sisters would have no choice but to participate. Even my first “Oh my God” moment with opera wasn’t in the audience, but backstage. One of my closest friends in elementary school was in the Met children’s chorus, and he brought me backstage for Boris Godunov. The music pulsated and the voices were huge and the colors were extraordinary. I watched them pushing the big sets around and the cast coming in and out. I was amazed at seeing all this seemingly random activity crystalize and become exact, and I thought, “How does this get put together?”

As a young composer, I found my niche in the chamber music world. Opera was this big, faraway thing; I preferred the intimacy of chamber music — the sense of dialogue. But then in 1988, I became artistic director of Town Hall. It’s a glorious space, with amazing acoustics and great sight lines, but it had been more or less dormant in the years since Lincoln Center opened. I wanted to put it back on the cultural map with eclectic and new programming. I conceived a festival meant to play out over 10 years, called “A Century of Change,” where each season we’d honor a different decade of the 20th century. In 1991, we covered the years 1910–1919, so I decided to produce Scott Joplin’s 1911 Treemonisha. It’s a piece with links to African-American music and African rhythms, the new sound of ragtime, Viennese operetta and early American musical theater.

I invited Betty Allen, the executive director of Harlem School of the Arts, to join as a partner with Town Hall. My good friend Tania León was the conductor. Wayne Sanders of Opera Ebony assisted Betty and Tania in finding the cast. It was an incredibly fraught experience — so many moving pieces, and never enough resources — and I was learning how to produce an opera as I was doing it. But it was joy-filled. Everyone was so committed, and so supportive of each other. We knew we were making something special. And we were doing it as a team. It was like chamber music writ large.

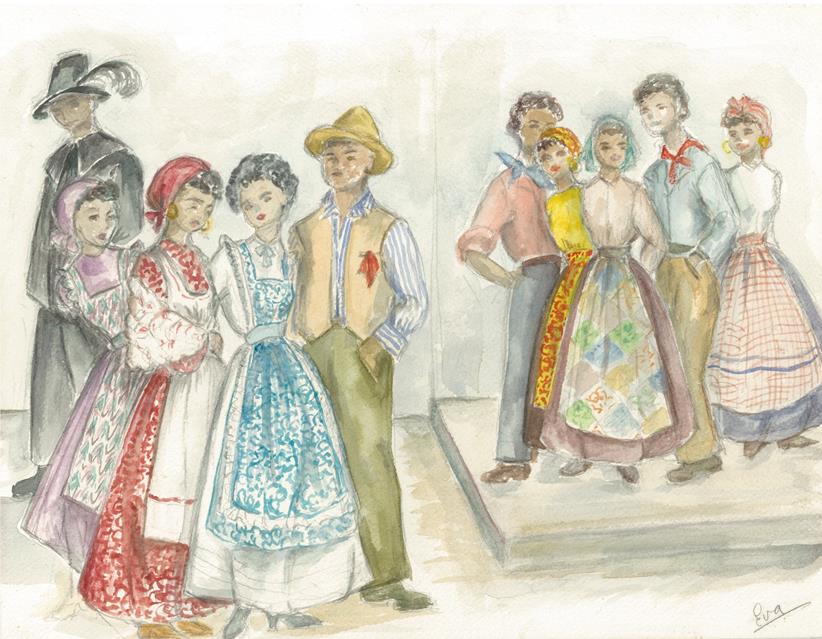

I realized the semi-staged production would look pretty plain with everyone in concert clothes, but I didn’t have enough money for costumes. I talked it over with my mother, Eva, who had trained as a fashion designer at St. Martin’s School of Art in her native London, and she said, “Maybe I can help.” She designed costumes, put together a team to make them and got a friend who was a fabric collector to donate all these beautiful cotton prints. All the performers with major roles went to my mom’s apartment for fittings. The costumes were beautiful, and they brought the production to life.

As a composer, I’ve mostly written instrumental music. I’ve always thought of myself as a storyteller, but in the past I perhaps didn’t have the courage to use words; my narratives were abstract. But when I got the notion to tell the story of a transgender person’s journey to self-actualization, I knew I had to do it as an opera. I had just produced a project at Symphony Space with Sasha Cooke and Kelly Markgraf, and I started thinking, “What if they were this person?” That was the genesis of As One. Mark Campbell and Kimberly Reed were the librettists, and the three of us are now working on our third opera together: Today It Rains, about Georgia O’Keeffe. All of our operas have been chamber pieces. The things opera has been charged with — that it’s grand and old and elitist — aren’t so true any longer, and largely because so much of contemporary opera is on a more intimate level, and more about the stories of our time and the people we know. I’m really excited about the state of contemporary opera, and that’s why I’m working so happily in this field.

This article was published in the Fall 2017 issue of Opera America Magazine.