Back Stories I

The companies who banded to form OPERA American in 1970 all brought to the table a track record of serving their communities. Here’s a look at how three of them got there.

Opera Omaha

As Omaha, in the years after its 1854 founding, turned into a national transportation hub, its flourishing economy supported the construction of a number of grand theaters: Redick’s Opera House (1871), Boyd’s Opera House (1881), the Grand Opera House (1885). Although these “opera houses” mostly offered plays and vaudeville acts, touring opera troupes, starting with the Adelaide Phillips Company in 1874, did start playing Omaha. In 1890, Henry Abbey’s Grand Italian Opera Company came in with a company that included Adelina Patti and Lillian Nordica; in 1898, Nellie Melba starred in Il barbiere di Siviglia. Unfortunately, most of these 19th-century theaters are long gone, victims of fire or demolition.

In 1958, a group of local businesspeople and politicians launched the Omaha Civic Opera Society. It opened in the fall with a production of Madama Butterfly, in English, and went on to mount an ambitious, four-opera season in venues across town. Its repertoire over the coming years was a mix of standard-repertory pieces and rarities like La Périchole and The Ballad of Baby Doe, and the world premiere of Quivera, a one-act opera by Richard Valente, the company’s first music and artistic director.

In 1969, the year before the company became a founding member of OPERA America, it changed its name to the Omaha Opera Company; another name change came in 1974, when it became Opera/Omaha. The next year, the company moved into the Orpheum Theater, a 1927 vaudeville house. Opera/Omaha celebrated the move with a glittery production of Lucia di Lammermoor, starring Beverly Sills and the young Samuel Ramey.

In ensuing years, Opera/Omaha hosted singers like Catherine Malfitano, Neil Shicoff and Frederica von Stade; conductors like John Mauceri, John Nelson and John DeMain, who was music director from 1981 to 1990; and directors like Colin Graham, Jonathan Miller and Christopher and David Alden. A series of fall festivals in the late 1980s and early 1990s offered much unusual repertoire (Handel’s Partenope, Glass’ The Juniper Tree, Donizetti’s Maria Padilla, the world premiere of Hugo Weisgall’s The Garden of Adonis) and exciting young singers like Lauren Flanigan and Renée Fleming. Under the leadership of Roger Weitz, Opera Omaha, as it is now known, revived the festival idea in 2018, with the One Festival, combining performances of grand and chamber opera with surrounding arts events.

New Orleans Opera

The modern era of opera in “the Crescent City” dates to 1943, with the formation of the New Orleans Opera Association, which debuted that June in City Park stadium, moving inside to the Municipal Auditorium that fall. With Walter Herbert and then Renato Cellini as general directors, the company summoned a dazzling array of the world’s leading artists. A spin-off company, Experimental Opera Theatre of America (1956–1960), offered early performance opportunities to young singers like Mignon Dunn and John Reardon. Knud Anderson, formerly NOOA’s chorus director, took over as general director in 1964, continuing the tradition of offering big stars in standard repertoire, but also presenting the world premiere of Carlisle Floyd’s Markheim in 1966, starring New Orleans native Norman Treigle.

Months after New Orleans Opera joined OPERA America, Arthur G. Cosenza was promoted from resident stage director to general director, shepherding the company in its 1973 move from the Municipal Auditorium to the newly built Theatre of Performing Arts, now the Mahalia Jackson Theater and still the company’s home base. In 1998, NOOA launched an education/outreach ensemble, MetroPelican Opera, which brings opera into schools throughout the region.

In 1998, Robert Lyall took over as general director, a position he holds to this day. He oversaw the company’s response to the devastation of Hurricane Katrina in fall 2004. The storm wiped out the first part of the opera season, but the company was back in business that spring, with a civic spirit very much in keeping with New Orleans’ historic commitment to opera.

San Diego Opera

In 1947, a band of San Diego women formed a local branch of the Los Angeles-based Opera Guild of Southern California. It officially became the San Diego Opera Guild in 1950, with its main focus being the sponsorship of visits from San Francisco Opera. Performances initially took place in Russ Auditorium at the San Diego High School, an acoustically dreadful hall, but two years later moved the Fox Theatre, a movie palace and a somewhat more suitable space for opera. The limitations of these venues aside, the San Francisco tours gave local operagoers a chance to hear some of the greatest singers of the day, including Leonie Rysanek, Elisabeth Schwarzkopf, Joan Sutherland and Franco Corelli.

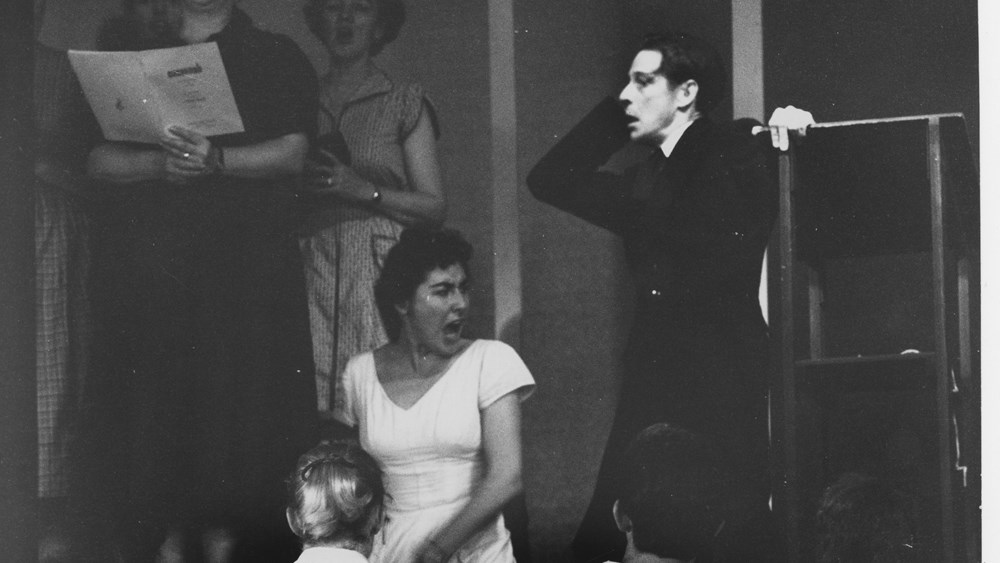

In 1965, the San Diego Opera Guild produced its first production on its own: La bohème, presented in English. This marked the birth of San Diego Opera, headed by Walter Herbert. That Bohème coincided with a move into a brand-new venue: the 2,945-seat Civic Theatre, which still serves as San Diego Opera’s main stage. Around this time, San Francisco Opera, facing financial pressures, ceased operating its tour. Now it was up to San Diego Opera to continue the city’s operatic tradition.

When the company became a founding member of OPERA America in 1970, it had already established itself as a force in American opera. Its casts included up-and-coming American singers along with stars like Norman Treigle and Beverly Sills; its forays into unusual repertoire included the premiere of Henze’s The Young Lord.

Herbert remained as general director until 1975. His successor was the stage director Tito Capobianco, who offered quite a few star-studded evenings, including, most notably, a 1980 Fledermaus that marked Sills’ last appearance in a fully staged opera and her only onstage encounter with Joan Sutherland.

Ian Campbell succeeded Capobianco in 1983 and remained at the helm for the next three decades, often gathering casts that were, if anything, starrier than ever before. His impending retirement in 2014, however, brought on a crisis, when San Diego Opera’s board voted to shut the company down. An eleventh-hour rescue, though, spearheaded by board members who wanted the company to remain open, and funded partly by a crowdsourcing campaign that brought in $2.2 million, allowed the company to continue operating into the foreseeable future. The “new” San Diego Opera opened in fall 2014 with La bohème. Back in 1952, it had been the first opera that San Francisco Opera had offered the city; in 1966 it had served for the company’s maiden production; now it was the vehicle for launching San Diego Opera into a new era.

This article was published in the Fall 2019 issue of Opera America Magazine.