Renters & Owners

A company’s real estate status can affect everything from scheduling to marketing to repertoire.

For an opera company, a good home can be a great asset, enabling the art but also enhancing the brand and cultivating an enduring bond with audiences. But even the best living situations have their bad sides. Roofs leak and carpets wear. Landlords lay down the law. Somewhere between the time utility bills come due and the roommates start complaining that they’re not getting enough personal space, even the most precious venues can start to feel like prisons. The real estate status of just about every company — whether it holds the deed, rents from the city, crashes on a college campus or cohabits with other nonprofit organizations — engenders both pleasure and pain.

Some companies have achieved the American dream: a home they can call their own. Sarasota Opera has one as a result of a fortuitous maneuver in 1979. That’s when supporters came together to purchase the 1926 A.B. Edwards Theater: an elegant and ornate example of Mediterranean Revival architecture, listed on the National Register of Historic Places, that over the years had hosted stars like Will Rogers and Elvis Presley. The company got it at the bargain price of $150,000, put it through a three-year overhaul and reopened it in 1982 as the Sarasota Opera House. The 1,119-seat theater is as much of an attraction as the music. Funders give to the cause of singing knowing they are supporting history, too, and folks just like hanging out in the place.

The company’s ownership translates into income. It has rented the space out for everything from high school graduations to weddings. During the off-season,it uses the space to present a classic-movie series, a series of HD presentations of opera and ballet, and “Sarasota Opera House Presents,” featuring pop performers like Tony Danza. The cash generated has contributed to a robust financial situation, and in 2017, the company was able to add to its real estate portfolio with an adjacent 72-bed apartment complex, providing housing to visiting artists.

Ownership does have its drawbacks: The theater’s size makes it perfect for Verdi and Puccini, but certain parts of the repertory are out of reach. It’s too small to generate the kind of revenue needed for a Ring cycle, and too big for chamber opera, which Richard Russell, Sarasota Opera’s executive director, says he would consider if another venue were available. The company also has the responsibility of maintaining an important community asset. When the place needed an upgrade in 2008, Sarasota Opera alone had to raise the $20 million. Meanwhile, old buildings have their quirks: in this case, a utility bill of $16,000 a month.

But one benefit outweighs all other factors: Sarasota Opera can control its performance and rehearsal schedule without having to worry about other tenants. That’s especially important in a warm-weather mecca where arts groups need to present in winter at the peak of tourism. “All of the other arts organizations here are fighting for space all the time,” says Russell. “We are lucky to have our own.”

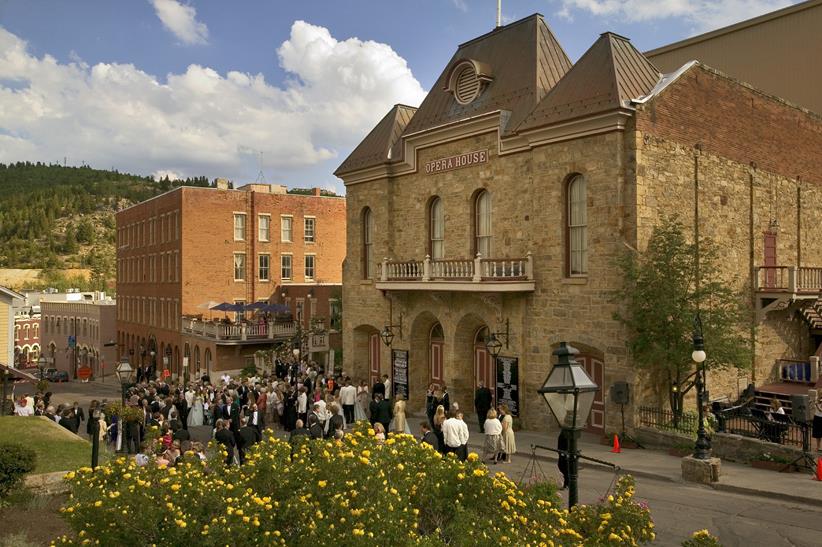

The identity of Central City Opera is similarly tied to its ownership of a historic venue: the Central City Opera House, a 550-seat ornate gem of a theater built in 1878 during the mining boom in the Colorado Mountains. Aside from the theater itself, the company owns 27 historic properties in town: houses, a barn and a hotel. Part of its charge is to act as a steward of all those properties. All are put to creative use: The barn doubles as a black box theater; the houses provide free accommodations for artists and administrators during the six-week, summer-only season; the hotel hosts fundraisers.

The situation creates benefits — and headaches. Central City Opera is one of a kind; people travel across continents to experience its intimacy and authenticity. But maintaining history involves obligations most other companies couldn’t imagine, like managing hundreds of thousands of dollars in preservation grants from government agencies and constantly overseeing renovation projects. The properties have no heat, so they can’t generate income in the off-season. (For the most part, the company offers them up to the public for local events at no charge.)

Meanwhile, the size of the opera house limits both the type of production the company can stage and the revenue it can expect from ticket sales. The venue has steep stairs and no easy access to restrooms: serious obstacles for an art form that serves many older customers. The company has tried staging shows in larger venues, such as in Denver 38 miles away, but in the eyes of many patrons, that’s just not the Central City experience. “Our reputation is tied up with the opera house,” says Chief Financial Officer Scott Dessens.

Lyric Opera of Chicago grapples with its own stewardship responsibilities. It owns and manages the Lyric Opera House: a 560,000-square-foot, 3,563-seat theater within a larger building. A crucial part of the city’s history, the theater is an Art Deco treasure whose famous columns, curtain and painted ceiling date back to 1929. Lyric was a tenant until 1993, when it bought the theater space and offices and instituted a $100 million “Building on Greatness” capital campaign, funding a massive renovation.

Everything from the ventilation system to the seats went through an upgrade, and an on-site rehearsal space that mirrored the exact dimensions of the stage was added. The company’s ownership has allowed a rental partnership with the Joffrey Ballet, which now uses the house as its home base.

But the continued maintenance of a 90-year-old facility is not something to take lightly. Until recently, that full-time job fell to Rich Regan, Lyric's former vice-president and general manager of presentations and events. Regan maintained a planning budget stretching three decades out. “I need to be able to plan years and years in advance with respect to bigger expenses,” he says. Since the opera company is the landlord, it must pay for all fixes itself: like the replacement of air chillers every 25 to 35 years, a job that can run into the high six figures.

Still, whatever headaches ownership may bring, they can pale next to the issues that arise when an outside property owner controls the site, as Opera Orlando learned this year. The company formed in 2016 from the ashes of the Florida Opera Theatre. It currently performs in multiple venues, including the 294-seat Alexis & Jim Pugh Theater, part of the nonprofit Dr. Phillips Center for the Performing Arts. Like the Orlando Ballet and the Orlando Philharmonic, Opera Orlando had planned to move into the art complex’s newest addition, the 1,700-seat Steinmetz Hall, set for completion next year.

But complications came up.

Florida Opera Theatre had been slated to use the hall, built largely with revenues from a tourism tax, as a resident home — with low, resident-company rates. Unfortunately, the Center doesn’t recognize Opera Orlando as the same company and refuses to grant it the same status as the ballet and orchestra. All three companies are currently in a squabble over the amount of rent they will have to pay, a public dispute that has cast a shadow over what should have been a joyful up-grade for Opera Orlando. Meanwhile, the company sees its survival hinging on a move out of the Pugh Theater, which has no orchestra pit, into a larger space — an especially pressing concern given the tastes of its audience base. “The audience here wants grand opera,” says Gabriel Preisser, the company’s executive and artistic director: in other words, the kind of opera that the Pugh cannot support.

Fort Worth Opera’s operations are entirely governed by its relationship with Bass Performance Hall — a space it shares with the Fort Worth Symphony Orchestra, Texas Ballet Theater and the quadrennial Van Cliburn International Piano Competition, along with megabuck-generating touring shows like Hamilton. “We are the last ones to choose our weeks,” says Tuomas Hiltunen, FWO’s general director.

Opera Theatre of Saint Louis’ rental arrangement for the Loretto-Hilton Center is altogether a more sanguine one. The theater sits on the Webster University campus in suburban St. Louis, the scenic grounds and communal tent allowing audience members to picnic before the show or share a drink with the artists afterward. The university serves not only as landlord, but as talent pool: OTSL works closely with students and hires the most skilled graduates onto its staff. To be sure, the theater itself, with its thrust stage and deep, narrow orchestra pit, is by no means a conventional opera house, and its use entails all manner of elaborate production and musical workarounds. But according to Andrew Jorgenson, OTSL’s general director, the theater’s very limitations have been instrumental in shaping the company’s identity as a champion of theatrically charged stagings, especially of new and recent American works.

It is, in Jorgenson’s words, “a hotly contested space.” Sharing the venue with both a professional theater company and the college’s dance department, OTSL is forced to limit its performances to a compact May-to-June season. Not that this is necessarily a problem. Jorgenson says: “This con-centrated period of time, when the nation’s opera eyes fall on Opera Theatre, works beautifully.”

The Dallas Opera is also a tenant, albeit one in an enviable situation. It is based in the Margot and Bill Winspear Opera House: a 2,200-seat facility in the AT&T Performing Arts Center designed for the company by Norman Foster and completed in 2009. The size makes it less than ideal for smaller productions, which the company stages offsite. But the acoustics in the bespoke hall make it ideal for large-scale opera. “It has this rare quality of giving great bounce-back to the singer without sacrificing tone,” says David Lomeli, who is TDO’s director of artistic administration and is also a former tenor.

The entire 40-year history of Boston Lyric Opera, meanwhile, has been shaped by its “renter” status. For two decades its main venue was the downtown Shubert Theatre. But inherent tensions caused the relationship to fray. BLO didn’t control the calendar and often couldn’t secure the dates it wanted. The theater’s cramped lobby space left little opportunity for patron amenities before shows and during intermissions. Worse still, the company was forced to use the theater’s ticketing vendor and couldn’t take advantage of customers’ information for marketing purposes.

BLO severed ties with the Shubert in 2015. It is now a fully itinerant arts organization: a situation that presents difficulties, but has generated creative, audience-building solutions. The company performs in unusual venues all over the city, like the basketball gym where it staged Poul Ruders’ The Handmaid’s Tale this past spring, or the ice rink that served as an immersive environment for this fall’s Pagliacci. The venues draw in quite a few audience members who might not be attracted to traditional mainstage operatic offerings.

“The doors we’ve been trying to open are opening,” says Esther Nelson, BLO’s general director. “We’re doing this not because we’re brilliantly prophetic, but because we were thrown into it. It’s the lemonade we’re making out of lemons.”

This article was published in the Fall 2019 issue of Opera America Magazine.

Ray Mark Rinaldi

Ray Mark Rinaldi is a veteran arts writer and critic whose writing has appeared in Opera News, Chamber Music, Inside Arts, and the Denver Post.