The Advocacy Playbook: Resource-effective strategies for working with public officials

There may not be as much public arts funding in America as there is in Europe, but there is certainly enough that many opera companies are still working to claim their share of the pie. The need to advocate consistently and well came into sharp relief when the coronavirus pandemic came along, shutting down performance venues and cutting off revenues. Federal, state, and local governments were dividing up relief funds for struggling businesses, and many arts groups found they did not have an effective voice that could argue for their share of the money.

“It really was an immediate call to action. Companies jumped in to prioritize their relationships, their conversations, and their advocacy efforts with government at all levels,” says Amy Fitterer, who oversaw research for OPERA America’s recently released Advocacy Guides, which address best practices, needs, and challenges related to government relations Since the pandemic, there has been an increased effort to make advocacy a critical, and relentless, part of opera companies’ operations. Company leaders have made new friends in crucial, decision-making positions and formed partnerships with other arts organizations to raise the volume of their pleas regarding funding, artist visas, voting, workers’ rights, and more. But they have also come to understand that building and maintaining those connections is a lot of work, and perhaps more labor-intensive than their squeezed staffs were set up to handle. “That was a major challenge to doing government affairs work,” says Fitterer. “It wasn’t that people felt it lacked value — it was that they just didn’t have the capacity to prioritize it.”

Today, many companies are taking a deep look at their advocacy operations. Each opera company needs its own plan of action, and one that is based largely on local conditions and questions. In general, building lobbying coalitions with other local arts groups and making a consistent effort instead of only appealing during funding cycles emerged as consistent strategies.

To provide a snapshot of current practices, OPERA America spoke to five companies about their strategies for maximizing their advocacy efforts.

Santa Fe Opera’s Comprehensive Strategy

The Santa Fe Opera enjoys some leverage when it comes to winning support from local leaders: With more than 700 workers at peak season, it is one of the top employers in its home city, and with an audience draw that tops 80,000 ticket- buyers a year, it is a leading driver of tourism in a state whose economy relies on a steady stream of well-heeled visitors. The company works vigorously to make sure decision-makers remember those numbers and shares that responsibility among multiple staff members: “We have a whole government relations team that spans the executive office, our education and community engagement teams, and our development office,” says General Director Robert K. Meya.

The opera makes regular visits to the New Mexico Legislature and meets frequently with public officials from across the region. When lawmakers convene at the state capitol for the start of their annual session, they are greeted with music — the company sends high school students who take part in its vocal training program to perform for free. The Santa Fe Opera also welcomes public officials to come visit the company. There is an annual Arts Advocacy Night that takes place at the final dress rehearsal for a mainstage production.

“We literally invite every one of the state legislators,” says Meya. This year, more than 200 legislators and their staff and family members attended Don Giovanni and heard a curtain speech from U.S. Senator Ben Ray Luján, a key supporter. That vigilance of staying in the public eye extends to the board of directors, which has its own arts advocacy committee that monitors legislation and sends out alerts asking its members to speak up for cultural causes.

“For us, this effort is always front and center,” says Meya. “It’s not something we do and forget about, it’s something we live and breathe every day.”

Minnesota Opera’s Nonpartisan Fundraising

For Minnesota Opera, advocacy revolves around strategic partnerships and smart politics. The company strategizes regularly with lobbying groups statewide, such as Minnesota Citizens for the Arts, which presses for funding from the state legislature. President and General Director Ryan Taylor credits the work of that citizens group for maintaining support for a local sales tax that raises funds for culture. “We probably get half a million dollars or more every year from that,” he says.

The opera company also teams locally with St. Paul’s Arts Partnership, a collaboration between the four tenants who perform at its home base, the Ordway Center. The partnership works to raise money from public and private sources to fund venue operations — separately from the fundraising each of those organizations undertakes on behalf of their individual artistic missions. “It’s money we don’t think we would be getting if we were just asking those same people for money for each of our institutions,” says Taylor. The company works closely with the Minnesota State Arts Board, a government agency that administers public grants and lobbies on behalf of cultural interests across the state. The board hosts regular meetings, sometimes virtually, other times in person, where arts leaders from different disciplines strategize on how to stay visible.

One of the most effective parts of that strategy is tapping into the persuasive power that comes from campaign donations given by the company’s patrons to political candidates, an effort that is coordinated state-wide through the arts board. “We actually do a lot of political fundraising,” Taylor says. “The arts board helps us coordinate an effort to make sure that when our donors are giving, they are tagging their donations as an arts donation.” The board encourages its supporters to donate to candidates financially but is careful not to ask them to give to a specific candidate. (As non-profits, opera companies must remain neutral.) The board also asks supporters to note that they are in favor of arts funding when they make campaign contributions to help keep the performing arts front of mind.

Crucial to the success of that idea is not taking sides between Republican and Democratic candidates, but making sure both parties get the message. “We let the donors decide where their money is going, but we ask them to bundle their contributions under this arts flag so that it amplifies the message that the arts are important to all parts of the community and not just one party or the other,” says Taylor.

Sarasota Opera Behind the Scenes

Unlike Minnesota Opera, Sarasota Opera is steering clear of any kind of grassroots political activity. There are just too many landmines at the moment, says General Director Richard Russell.

The state of Florida has historically supported the arts financially, but this year, its governor, Ron DeSantis, made headlines by eliminating all $32 million in the state budget that was devoted to cultural groups. Sarasota Opera was set to receive about $70,000 before it suddenly vanished in June. What followed was a loud and divisive public debate over whether the government should be involved in arts funding at any level. Even some of the company’s patrons and board members argued against such support of the arts.

So, Russell works in other ways to keep the company visible. Sarasota Opera continues to collaborate broadly with organizations, such as the Florida Cultural Alliance, a state-wide lobbying group that will argue on behalf of the arts going forward. Part of his plan is to “leverage some of my donors who are connected politically with some of the local legislators to continue pressing our case and making sure they are aware of what we’re doing,” he says.

The company’s other stream of government funding, from Sarasota County, remains intact for now, though the company does lobby to make sure arts groups remain on the list of grantees who receive a portion of revenues from a tax on hotel rooms that is collected with the purpose of bolstering tourism.

Sarasota Opera’s current strategy is to connect wherever and whenever possible, and not just when funding cycles are imminent. This is a labor- and time-intensive effort for the staff. For example, the company maintains a presence on local boards, according to Russell. “I sit on the tourist board, one of my colleagues sits on the economic development board, and another one sits on the chamber of commerce.”

And in between all the meetings those roles require, Russell tries to maintain human-to-human connections. He invites officials to performances — sometimes they come, sometimes they are not interested — and he always formally, and deliberatively, acknowledges when help comes his way. It’s a mix of good manners and smart politics. “It’s always important to thank them for their support,” Russell says.

Opera Maine’s Lobbying Coalition

Like its peers in the art business, Opera Maine hoped for a share of pandemic relief funds that were being allocated by local, state, and federal agencies. However, the Portland-based company found itself without a strong voice to press its case.

Opera Maine became a driving force in the formation of the Performing Arts Leadership Alliance, which brought together executive directors of the state’s largest nonprofit arts groups for an ultimately successful drive to win part of the money that went to businesses big and small. “We formed this alliance to talk about how we were struggling and what we needed help with and how to get it, so that we could all be on the same page,” says Caroline Musica Koelker, the company’s executive director.

The group continues to work on arts causes going forward, and its efforts complement other groups that have emerged lately. “We also have a fairly new organization called the Cultural Alliance of Maine, and part of their mission is to advocate for the cultural sector at the state government level,” Koelker says.

In Maine, much arts funding comes from state economic and development funds, and it is not designated specifically for arts. So, the culture sector competes with other businesses for attention, and it is not always natural for officials to understand the arts are a crucial part of the economy. “The arts are not first and foremost on their minds,” Koelker notes. “Even in the way they frame the application questions to make that money available — it’s obvious we’re not a part of what they’re thinking of.”

Koelker considers elected officials in Maine to be largely supportive of the arts — from senators in Washington all the way down to its representatives in the state legislature. But while they are accessible and amenable, Koelker knows the company and its colleagues need to keep up the work, touting not just economic impacts but art’s ability to make community connections and foster mental health. “We want to also point to the quality of life because we know, especially coming out of the pandemic, that is so much more important now.”

And she has a bigger plan: “Ideally, what we would like to see in the future, is that we have an arts lobbyist in the same way that Maine has a lobster lobbyist,” she says. “We know we have a stronger economic impact than Maine’s lobster industry, and yet we don’t have someone in the room when conversations are happening.”

Opera Theatre of Saint Louis’ New Strategy

Opera Theatre of Saint Louis also ramped up its advocacy efforts during the pandemic to fight for a share of the state relief funding. The company learned that it had to lobby hard via the existing Regional Arts Commission of St. Louis to win a share for culture. Part of that effort involved a letter to government bodies stressing the role of arts and the need for help. Cultural leaders, including OTSL General Director Andrew Jorgensen, lent their signatures to that letter.

There was some success. The company did get a share of the assistance allocated to culture from the city of St. Louis. But it was unsuccessful in winning support from a second government agency, St. Louis County. “The key point is that we have realized we need to be doing more,” says Development Director Linda Schulte.

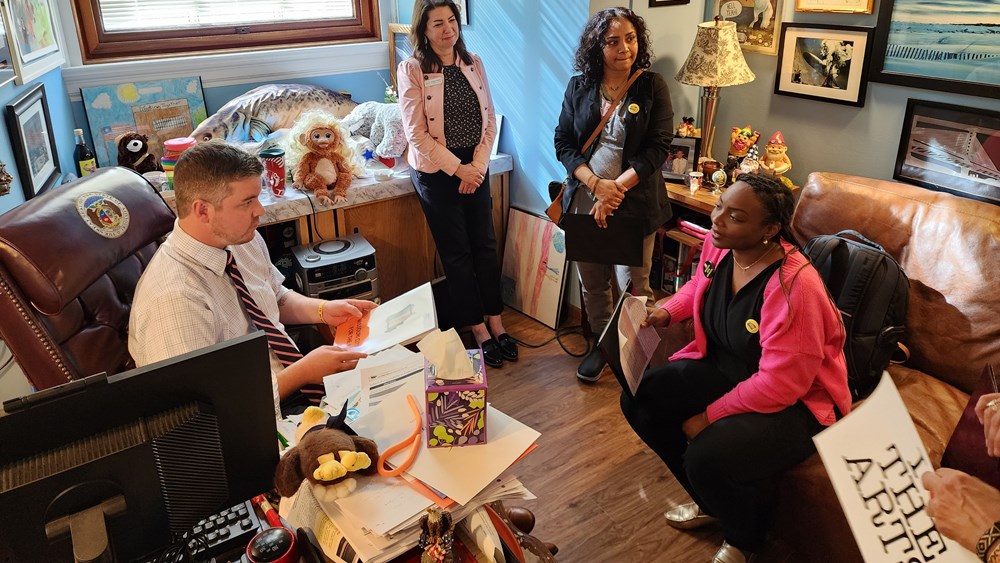

Opera Theatre of Saint Louis does have an active, in-house advocacy committee made up of staff members in various departments that meets regularly to assess the political landscape, though its efforts are mainly focused on the company’s participation in an annual arts advocacy day at the state capitol in Jefferson City. The Regional Arts Commission hires busses to drive arts supporters from across Missouri to the event.

This year, the strategy was a little different. In past years, Schulte walked around the capitol herself, or with a board member or volunteer from her organization, connecting with legislators and their staffs. Recently, the commission decided to take a more holistic approach. It organized lobbying teams across arts organizations, grouped by role. Each lobbying team had representation by people who work in operations, produce education programs in local schools, or do fundraising with local businesses, along with artists who make the work that entertains audiences. “Having such a broad range of perspectives in that room and having those groups so thoughtfully curated really felt like it made a difference this year,” Schulte says.

A New Advocacy Playbook

- Get out the vote during this fall’s election season. Visit operaamerica.org/Vote to register or check your voter registration

- Make your company’s voice heard at the local, state, and national levels without hiring additional staff or contractors

- Explore what strategies are currently resonating with public officials and how you can tailor them to your needs

- Win over local government officials to your cause

- And much more

Share in this crucial work by exploring the toolkit and distributing the resources to your opera company’s staff and trustees.

This article was published in the Fall 2024 issue of Opera America Magazine.

Ray Mark Rinaldi

Ray Mark Rinaldi is a veteran arts writer and critic whose writing has appeared in Opera News, Chamber Music, Inside Arts, and the Denver Post.