Building Blocks

What are the components of a successful premiere? A panel of top opera creators puts them together.

Successful operas don’t emerge full-blown from their creators’ craniums. Instead, they often reach their final shape through an elaborate development process whose components may include workshops, orchestral readings and showcase presentations, with revisions large and small until opening night.

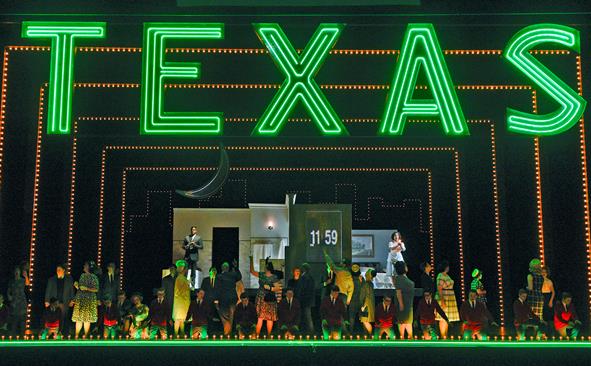

This January, as part of OPERA America’s New Works Forum, President/CEO Marc A. Scorca moderated a panel of leading composers and librettists to examine the components of a successful premiere. The discussion, titled “Good Parts = Good Premieres: Structuring Commissions,” brought together seven artists, all of whom launched successful operas in 2016: composers David T. Little (JFK), Missy Mazzoli (Breaking the Waves), Paul Moravec (The Shining), Jack Perla (Shalimar the Clown) and Gregory Spears (Fellow Travelers); and librettists Mark Campbell (The Shining) and Royce Vavrek (Breaking the Waves and JFK). The panelists offered a frank assessment about which pre-premiere processes helped them move forward — and which were hardly worth the effort.

Nearly all agreed that piano/vocal workshops, ranging from a few days to as long as three weeks, can offer tremendous support in shaping a piece; in fact, Moravec called them “absolutely indispensable.” The Shining received two piano/vocal workshops at Minnesota Opera: one when only the first act had been completed; the second of the full-length piece. The company’s artistic director, Dale Johnson, its music director, Michael Christie, and its then-head of music, Robert Ainsley, took part, along with director Eric Simonson. “I asked for feedback, and boy did I get it — good and hard,” Moravec said. “Their suggestions were spot-on. Whatever success this opera has, I owe as much to them as to Mark [Campbell] or anyone else.”

At a Breaking the Waves workshop, director James Darrah suggested that the first scene of the second act should be moved to the end of Act I. “I was having a heart attack,” Mazzoli recounted, “because for a composer, a beginning of an act is so different from an end — you’re setting up energy that reverberates through an entire act. But we came up with a compromise.”

One inherent limitation of these workshops is that a piano takes the place of a full orchestra. “Pianos don’t sustain — it’s a completely different sense of time and texture,” Moravec said. “It’s really difficult to know what a piece is going to be based on a piano/vocal workshop, so I am wary of situations where the workshop is used to assess the work as if it were finished,” said Little. “Workshops absolutely provide an opportunity to address details of vocal writing, dramaturgy and pacing, and this can be very valuable, but it’s just a step along the way.”

In some cases, producers will organize libretto readings earlier in the process to give the creators a sense of how the opera works as a piece of drama. But the panelists found these readings fairly unhelpful as a development tool. One problem is the inherent dissimilarities between spoken theater and opera. “A libretto is not supposed to be spoken; it’s supposed to be sung,” Campbell said. “I think it’s fine to do a private reading if a composer requests one. But there’s also a danger in actors giving line readings that throw a composer off from their true meanings.”

“A big part of the composer’s job is to create characters through music,” said Little, “That’s why I try to avoid readings where the libretto is performed in such a way that the characters are being defined for me through the actors’ delivery.”

Vavrek, for his part, discourages formal readings of his librettos. “It’s money that can be spent elsewhere,” he said. “You spend so much time getting actors’ intentions rather than just what you’ve put on the page.” He prefers instead to gather a project’s creative team and read the libretto himself. Vavrek’s readings “give me all I need to move forward and create the characters in music,” Little said.

Often, piano/vocal workshops will culminate in a reading in front of an audience — a practice that elicited differing responses from the afternoon’s panelists. Moravec said he was glad to have a workshop audience for The Shining. “The audience is the third element in the process — it isn’t just the creators and the performers,” he said. “You learn a lot from people who are listening cold, especially if you have funny elements: You need to know if the jokes are landing, and if they aren’t, nobody laughs. Or they might laugh inappropriately, which is another problem.”

“I recognize that having an audience at a workshop can be important institutionally for an opera company, and I respect that,” said Little. “But what I gain most from a workshop is being an audience member myself and listening to the piece straight through as if I hadn’t written every note.”

“We didn’t do feedback sessions [for The Shining],” said Campbell. “We didn’t go around saying, ‘Did you like it? Weren’t you scared?’ It’s enough to feel what’s going on during the workshop, and whether the story is making a connection with the audience or not.”

The presence of an audience at Fellow Travelers workshops, produced by Cincinnati’s Opera Fusion: New Works program, gave Spears some necessary input for honing the work. “It gets me excited in a devilish way because they’re the ones who are on stage for me,” Spears said. “There’s a moment in every opera, except maybe a perfect opera, where you can feel the audience’s attention shift: The audience makes the decision about where the structural flaw is in a piece. When I’m in a workshop with an audience, I’m not really listening to the piece all that much — I’m listening for that shift.”

The workshop process inevitably provokes feedback from many different quarters. The panelists reported that deciding what to take in and what to ignore can be a delicate operation. “It’s up to me to process it,” said Campbell. “It’s not necessarily useful if some nasty donor comes up and says, ‘I just don’t like this story.’ But if Dale Johnson whispers, ‘I think things are kind of floaty right now,’ I know what he means.”

Little requests that feedback come through e-mail, which allows him time and space to process the comments. “If I were to be barraged with comments, they would all disappear — I wouldn’t remember a single one,” he said. “Write me what you think, and I promise I’ll consider everything, but I need to go through that at an appropriate time. I feel it is vital that I understand my own reactions to a work before I can begin to consider the reactions of others.” As hurtful as negative comments might be, some panelists noted that praise should also be approached with caution. “When people throw around words like ‘brilliant’ and ‘masterpiece’ at a workshop, it’s hard for us to do our job,” said Campbell. “I’d much rather be told ‘Scene 3 is too long’ because I can work with that.” Spears said he asks observers to list their three favorite things and three least favorite things, “and I usually ignore the three favorite things.”

Producers will occasionally bring a person into the development process specifically to give feedback: the dramaturg. Both JFK and Breaking the Waves used the services of Cori Ellison, dramaturg at Glyndebourne Festival Opera; on Breaking the Waves, she was joined by Michael Cohen, a dramaturg from the world of the theater. “We went through every page of Breaking the Waves,” Vavrek reported, “and the dramaturgs would say, ‘Do you really mean to put this word on a whole note? Why do you have this in F-sharp?’ So much of what we do is intuitive, but the dramaturgs held us accountable for our choices.”

“You’re like a doctor, a diagnostician,” Ellison said, in a later conversation. “You have to be empathetic, while being the most objective eyes and ears in the room.” The use of dramaturgs in opera development remains unusual; in most cases, the director will take on a dramaturg’s role in shaping the material. But Ellison cautioned that the two roles are different: “A director’s job is to put the piece on stage, and if there are problems, fix them,” she said. “The dramaturg’s role is to point out where the problems are in the first place.”

But in the development of most new operas, it is indeed the director who serves as dramaturg. “[James] Robinson really stewarded Shalimar from beginning to completion,” Perla said. At Fellow Travelers’ Opera Fusion workshop, director Kevin Newbury asked for changes in one scene that he felt was falling flat. “It was the only time in the workshop I kind of disagreed with him, but I stayed up till three in the morning rewriting,” Spears said. “We brought in singers the next day, and it sounded good. We never would have found the solution to that scene if I had done it on my own.”

In some cases, a producing organization will sponsor an orchestral workshop for a developing opera. It’s an expensive undertaking, which is probably why it’s by no means a universal practice. But it can provide a composer with an enhanced capability for fine-tuning. “It gives you a chance to tweak the orchestration away from the other moving parts,” Spears said.

Moravec had never had an orchestral workshop before The Shining, but he was grateful to Minnesota Opera for providing one. “It’s helpful with all the technical problems, like balance,” he said. “I could fix it six months before opening, so then I didn’t spend the final rehearsal time trying to hear the singers: We could focus on the drama. Another good reason for doing it is that if you’re working with the orchestra that’s going to play it, they become part of the action. They take ownership of the piece.”

Casting can be a key component in the opera-development process. If the cast takes shape while the work is being honed, it can provide a welcome degree of focus to the creators, letting them tailor their work to the individual performers’ personalities and strengths. “I love to know who I’m writing for,” Spears said. “I know it inspires my best music, but I also know that historically, all the great roles were written for specific singers.”

When Moravec was developing The Shining, he consulted his two leads, Brian Mulligan and Kelly Kaduce, about how their voices worked. Both provided him with lists of elements that showed their voices off to best advantage — information he incorporated into the score. “I think of Martin Scorsese,” Moravec says. “One of the keys to his success was that he was always working with the same actor, Robert De Niro: He used him as an instrument. The more you can do that, the more everybody wins.”

Perhaps the most important element in creating success is also the least tangible: the full support of the opera company itself, with everyone working toward a common end. Moravec offered a rule of thumb from Stephen Sondheim: “Make sure everybody is working on the same show.” An effective development process is an opportunity to synchronize all of an opera’s moving parts, and to get buy-in from all participants.

Vavrek noted that the institutional support received by both JFK (from Fort Worth Opera and American Lyric Theater) and Breaking the Waves (from Opera Philadelphia) fostered the best possible circumstances for engendering success. “It felt like we had every creative resource necessary,” he said. “We defined what we needed and we got those things, and it made for a very robust creative space.”

This article was published in the Spring 2017 issue of Opera America Magazine.