Instagram Moments

The social media platform offers dynamic possibilities for reaching new audiences.

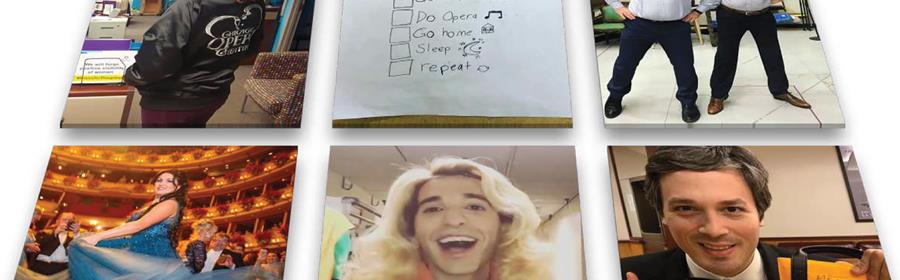

Here’s what you’ll find on Chicago Opera Theater’s Instagram feed: Music Director Lidiya Yankovskaya on the podium for Iolanta. Her infant son Artie reading the orchestra score to The Life and Death(s) of Alan Turing. School kids’ drawings from COT’s Opera for All program. A video greeting from The Scarlet Ibis cast member Quinn Middleman, introducing us to her cat Clementine. Scott Gryder, COT’s audience services manager, lip-syncing to Whitney Houston while waving a container of cupcakes.

What you won’t find: any direct pitch to ticket buyers. The text accompanying the images directs viewers to COT’s website — with a few clicks, you’ll eventually reach a sales page — but that’s hardly the main focus. “It’s about the connection between the pictures and the audience,” says Laura Smalley, the COT marketing and communications associate who oversees the feed. “We want them to be connected to us first.”

In the nine years since Instagram’s introduction, the social media platform has become an international phenomenon, with a user base now estimated at one billion. Its mash-up of pictures and videos have proved a stunningly effective means of image-building and fan cultivation that works not just for sports stars, pop singers and actors, but also for opera companies and performers. Opera feeds don’t generate followers in the same numbers as those of soccer star Cristiano Ronaldo (157 million) or pop diva Selena Gomez (148 million), but they can still attract significant Instagram attention. The 437,000 people following Anna Netrebko track the Russian diva’s charmed life from Prague Castle to Radio City Music Hall to Soho Square. Harpist Emmanuel Ceysson has drawn 8,500 followers through droll, but deeply musical, video clips that show him playing in the Met’s pit while mouthing along with the singers onstage.

“When I look at these accounts, I could be seeing pop stars or indie-rock singers,” says Nancy Baym, a principal researcher with Microsoft Research and the author of Playing to the Crowd, an analysis of musicians’ use of social media. “There’s nothing that screams, ‘This is a high-culture activity.’”

In the view of Jill Walker Rettberg, leader of the Digital Culture Research Group at Norway’s University of Bergen, the face that opera presents on Instagram reflects a broader cultural shift in the relationship between performers and audiences. “In the 20th century, celebrities — especially performers standing onstage — were distant figures,” she says. “Now, there’s an expectation that you can get to know them a bit more. You see them behind the scenes. They respond to what fans think. That reciprocity is important.” Citing the “direct connection between musicians and their fans and patrons” depicted in the film Amadeus, Rettberg argues that the approachability of Instagram is returning classical music to an older mode of audience interaction.

“It’s not a new idea that part of being a good artist is being an interesting person,” says Anthony Roth Costanzo (8,100 followers). “Instagram is just the modern-day extension of that.” The countertenor’s feed includes music videos from his Glass/Handel album, any number of backstage selfies with notable visitors (pop star Sam Smith, ballet dancer David Hallberg, kabuki performer Ebizo Ichikawa), and videos of his flamboyant end-of-run curtain call for English National Opera’s Akhnaten (#diva) and of the full-body waxing he had to endure for the production.

Since users sometimes share their favorite content, Costanzo’s posts reach people who may have had no previous awareness of him. “It shows you what your friends like,” he says. “If you have no idea of who I am, but you see a video someone has shared in a feed, you may think, ‘I wonder who’s singing?’”

The platform allows Costanzo not just to get this message out, but to maintain a form of personal contact with his fans. When they send direct messages, he responds. “It doesn’t feel as onerous as answering 500 e-mails,” he says. “Because of the informality of Instagram, it’s not like you have to write ‘Dear so-and-so, all the best.’ It’s an accepted practice to respond with just a heart. If I’m in a hurry and I have 10 messages in my inbox, I can go through them in 45 seconds.”

“For me, Instagram is about communication with my fan base,” says mezzo-soprano Jamie Barton (13,900 followers). “They say a picture is worth a thousand words — and I’ve probably got a thousand pictures up. I get comments from people who were at a particular show, as well as people who’ve never been to an opera but found me through searching hashtags.”

Barton, who came out as bisexual five years ago, regularly gets Instagram messages on the topic. “I’ve been impassioned about being visible, and I get a lot of people writing to me and thanking me,” she says. “My visibility has influenced them to feel more present and more proud of who they are. These messages make my day in a way I can’t even describe.”

One aspect of the platform that Barton finds appealing is its egalitarianism. Within it, fledgling performers keep company with the likes of Renée Fleming and Joyce DiDonato. “I know a lot of young artists, and I get to follow their stories right along with the top dogs of the field,” Barton says. “It allows access for everyone, which is really important in a field that has traditionally been elitist. I believe very much that the future of opera is inclusivity, and Instagram provides a platform for that.”

Instagram allows its users to post stories: images that pop up for a day, then disappear. Their ephemeral nature makes them even less formal than permanent content. Ideally, a story will seem like an unselfconscious product of impulse: a further means of erasing barriers between users and their audience. “I’m becoming a big fan of stories,” says Beth Stewart, a publicist who advises clients like Barton on their Instagram use. “They’re quick and impermanent. I’m not a fan of over-curated: I want to see a human being.”

For opera companies, continually seeking to offset the graying of their audiences, Instagram provides an opportunity to reach a younger demographic: 68 percent of users are under 35. In comparison to its corporate parent, Facebook, it transmits a feeling of youth. “Instagram is a fun social gathering where you might feel something exciting,” says Stewart. “Facebook is like listening to your uncles arguing about politics in the living room.”

Savvy opera companies work to maintain a sense of fun in their feeds. In general, the production photos you might find on a company’s website make a weaker Instagram statement than behind-the-scenes glimpses that convey an element of the unexpected. Dale Edwards, Houston Grand Opera’s director of marketing and communications, points to a magazine item about Pearl Fishers designer Zandra Rhodes that the company reposted on its Instagram account. “Would we normally do that for an article?” he says. “No, but she’s a fashion designer and she has hot pink hair.”

One common Instagram tactic is the takeover, in which a company hands over its feed to an outside party. The Met, promoting the U.S. premiere of Marnie, handed its feed over to Costanzo, who donned one of Arianne Phillips’ mid-century-chic costumes and tried to pass as a member of the “Marnettes”: the doppelgangers who shadow the title character throughout the opera. The creators of HGO’s takeovers have included its Studio Artists and Pearl Fishers star Lawrence Brownlee.

“Larry was able to log on as he saw fit,” Edwards reports. “He showed what goes on in a singer’s life: coffee in the morning, warm-ups rehearsals. He’s a guy who likes to have fun, and he has fun doing his job, which is singing opera. It helps break down misconceptions of who opera singers are, and of what we do.” Brownlee’s takeover boosted the number of HGO’s followers. “Does that mean that those people would come and buy a ticket? Probably not,” says Edwards. “But he’s got followers all over the world who became aware of HGO. It puts us in a better light.”

HGO makes further use of Instagram by identifying local social media influencers — users who, through their feeds, purportedly exert significant influence on their peers — and inviting them to the opera. The company looks for people with a notable number of followers, especially those who highlight trendy events. The aim is to position opera as a date-night option for young people.

The Santa Fe Opera has in recent seasons brought together local influencers for “InstaMeets” at dress rehearsals, where they sit in a special section of the house with unrestricted views of the stage. They’re encouraged to take pictures — and, most importantly, post them. On two occasions last summer, the company hosted a contingent of 20 “macro-influencers” for a full evening of events, including behind-the-scenes tours and champagne dinners. A photo contest in conjunction with the InstaMeets generated 938 photo submissions, with a chance to photograph a performance from the wings as the grand prize.

The program was specifically put in place to attract young and first-time operagoers, and to broaden the company’s social media footprint. “They wanted to cultivate an audience for the future, but it wasn’t in their budget,” says Caitlin E. Jenkins, co-founder of Simply Social Media, the consulting firm that runs the events. The resulting photo blasts have swelled the number of Santa Fe Opera followers on Instagram (from 8,992 to 9,939 over the summer 2018 season) and on Facebook, as well (22,961 to 24,810).

It is not clear that these numbers have resulted in an uptick in either box-office sales or new ticket-buyers. But Instagram advocates are quick to point out that a sales metric may be well beside the point. In the words of Dale Edwards: “Instagram is not for selling; it’s for engaging.” “It’s a powerful tool,” says Nancy Baym. “Especially if you throw in some cats with incredible green eyes.”

This article was published in the Spring 2019 issue of Opera America Magazine.

Fred Cohn

Fred Cohn is the former editor of Opera America Magazine.