Inherited Repertoire: Revisited & Reimagined

OPERA San Antonio welcomed audiences back after the COVID-19 shutdown with a production of Rigoletto — one that was originally scheduled for pre-pandemic times but turned out to be ideal for 2022 in many ways. Though it was written in 1851, the themes remain apposite. “There are difficult topics that have to do with political corruption, young innocence, naïve love, and how feeling trapped by circumstances can compel a young person to make really cataclysmic choices,” says General and Artistic Director E. Loren Meeker.

To audiences in San Antonio, who have had hit or miss opportunities to see opera, Rigoletto felt new because so many people were seeing it for the first time. Its name recognition made it a safe bet for the seven-year-old company in a time when revenue was tight. The fact that OPERA San Antonio could rent a production (in this case, one developed by Boston Lyric Opera, The Atlanta Opera, and Opera Omaha) was another major plus.

Numerous opera companies have made a similar calculation in the past year and brought back inherited repertoire. But tackling these productions has also come with some difficult questions. Given the tremendous suffering of the pandemic, the racial reckoning of the Black Lives Matter and other social movements, and the war and political unrest currently shaking the world, how do opera companies produce inherited repertoire that still feels timely? Does it even have a place in the modern world, when there is such a movement to showcase new voices and new works?

Ethan Heard, artistic director and co-founder of Heartbeat Opera, firmly believes inherited repertoire has a place — with some updating. “Heartbeat has made it our calling card to intervene in the classics,” he says. “They don’t need to be in a museum. They don’t need to be on a pedestal.”

The company’s adaptation of Fidelio is a perfect example. In 2018, it transformed the opera into a 90-minute production with five principal singers and a chorus of more than 100 incarcerated people drawn from audio recordings at six prisons. It cut characters, moved a few scenes, and added a new English translation by Marcus Scott and Heard with some original dialogue. The characters were given more modern names, and their struggles were altered to be more 21st-century American. Stan (formerly Florestan) is a Black Lives Matter activist wrongfully incarcerated by a White supremacist prison warden. Leonore no longer has to dress up as a man to save the day; instead, Leah/Lee poses as a lesbian woman to seduce Marcy (Marzelline), the prison guard’s daughter.

“Marcy is a pretty naïve character without much depth [in the original],” Heard says. “Here, Marcy is a strong, queer Black woman in deep denial. As a queer artist, I’m excited to be putting Black, queer characters on stage in joyful moments. I told Marcy, you can be in a rom-com. The rest of us are in a tragedy.”

The production has continued to evolve. In 2020, Heard brought on more Black collaborators to update the show and reflect societal changes triggered by Trump administration policies and the murder of George Floyd. In 2022, when the show was remounted at the Met Museum, Michael Powell, a former member of KUJI Men’s Chorus at Marion Correctional Facility in Ohio who sang in the original prisoners’ chorus, was able to fly to New York and participate on a panel.

Numerous companies are looking to bring the production to their communities, and the opera has attracted many people who might not have taken in a more traditional version of Fidelio.

But Joel Ivany, artistic director of Edmonton Opera, is sympathetic to audiences who push back against the idea of revising inherited repertoire. “Opera people are the most passionate for what they love, meaning those who like Tosca love Tosca,” he says. “To be told or to think that won’t exist in the future is terrifying for them because it’s something they know and love. If it changed them, it could change other people.”

Edmonton Opera went ahead with a previously scheduled production of La bohème this year in part to honor its existing contracts, Ivany reports. But he also saw tremendous value in bringing it to life. “There’s no better way to show what opera is than La bohème. It’s incredible music. It’s an incredible love story. It’s flawed as well, but it’s on our side to think about how we make opera more accessible for people. In our culture and society, when people hear about opera, they think about horns and the large lady, and that’s only a sliver of what it can be. We need to fight for our space if people are going to give it a chance. Once they hear an orchestra and a passionate performer, they’ll be moved and want to know more.”

Christopher Hahn, general director of Pittsburgh Opera, says opera is a big tent and should stay that way. “Part of the audience is only interested in traditional work. Why not keep them in the fold by offering them what they know and love? Then there’s an audience that loves anything contemporary and different. Why not bring them into the fold? Making [the opera community] smaller and smaller, and saying we shouldn’t bother with the old tried-and-true pieces, is a massive miscalculation.”

In fact, inherited repertoire is still the thing that is bringing in the majority of audiences. “Our production of Il trovatore later this year is one of the things that’s been galvanizing our audience because in this community, it hasn’t been performed,” Hahn says. During the post-show talkbacks of a past production of Carmen, he asked people to raise their hands if they’d never seen it before. “Ninety percent of people put their hands up,” he reports.

Inherited repertoire can be fun, lighthearted, and a way to escape, which can feel necessary when the world feels so heavy, Ivany says. “I feel it’s more important than ever that this is a place where you can come to laugh, to cry, to time travel, to go on a vacation for two hours.”

There’s a time to escape from the things that make the world heavy, but some inherited repertoire pieces actually perpetuate the things that add weight to the human condition, including racism and sexism. It’s with these productions that companies are looking to make the biggest adjustments.

Meeker is involved in a reimagining of Così fan tutte for Arizona Opera. When General Director Joseph Specter approached her about the project, he had two questions. Was the story one that still needed to be told in 2022? If the answer was yes, how should they go about doing that?

Saying yes to the first question was easy. Answering the second was challenging. What this process of reimagining the show allowed Meeker to do was “really sit down and try to wipe my brain clean of preconceived notions about the piece while simultaneously leaning on that experience to ask, what are the traditions that are helpful, what are the traditions that are flawed, and how can we reinterpret and update this piece?”

She didn’t just look inside her own mind for answers. “I did a lot of phone calls with colleagues who have done multiple productions of Così and asked where they struggled most with the interpretation. The thing that kept coming up is, why does ‘women are like that’ have to be a bad thing? Why are they just pawns? Why can’t their choices be active and driven by them?” Her team’s new interpretation takes those comments to heart.

Intermountain Opera Bozeman recently reworked The Mikado into The Montana Mikado. “When we were planning our first season supposedly out of the pandemic, there was a desire to celebrate with repertoire we knew the community loved — and Bozeman loves Gilbert and Sullivan,” says Artistic Director Michael Sakir. “When The Mikado came up, it was important to me and to our board that we approach this piece with the judiciousness that it required.”

The company pulled together a team that included Soren Kisiel of Broad Comedy, who served as the writer and stage director, and faculty from the Asian studies program at Montana State University. “Everyone embraced the work’s satirical origins and the idea of doing a satire of modern-day Montana,” Sakir says.

The company also used the production as an opportunity to educate the community on why the original production was so problematic — and how the issues of racism it perpetuates are still a serious issue today. It created a series of webinars and community events, hosted by board members, that covered topics such as model minorities, cultural appropriation, and implicit bias. One night, a three-person panel of Asian performers and students talked about their wearying experiences facing down regular microaggressions.

The conversations were hard, but that didn’t keep patrons away. “People kept coming to these webinars and were in it to learn, and that gives me hope,” says General Director Susan Miller. “Many bought tickets for multiple nights.”

The latest project for IN Series is Othello/Desdemona, a two-night opera event led by Artistic Director Timothy Nelson. The productions have only five characters and a piano for accompaniment. An English translation painstakingly incorporated more of Shakespeare’s original language than Verdi and Boito’s interpretation.

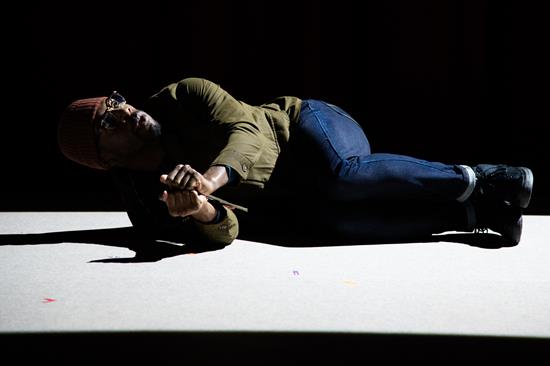

Nelson received permission from British artist Keith Piper to use his art installation “Go West Young Man” as inspiration for the set and video aspects of the production. “The photographs explore the commoditization of the Black male body and the line between fear and fetish. His artistic presence is huge,” Nelson says.

But perhaps the most important update is that the voices of Black men are allowed to come through thanks to four interludes that were composed by Matthew Evan Taylor and inserted into Verdi’s score. “The thing you can’t escape with Otello is it is White men talking about the Black experience,” Nelson says. “They do it with incredible eloquence, but it’s still Shakespeare and Verdi, so it’s very inauthentic. We’re owning that this is White men talking about racism and other voices need to be in the room.”

Nelson’s opinion is that rigid adherence to the traditional opera canon is what has caused the art form to struggle, even as traditional theater has remained popular. “We approach opera as if we were curators at a museum — that these pieces can’t be touched or fiddled with,” he says.

With problematic operas, that simply isn’t possible. “It’s not that people don’t like opera, it’s that they aren’t stupid,” Nelson says. “They don’t want to come see some White woman dress up as a geisha and stab herself.” If companies want to keep the good elements of inherited repertoire alive, they must adapt to changing times, circumstances, audiences, and artistic possibilities.

There is little doubt that inherited repertoire will continue to find its place in the modern world, either through reimagining or mindful revisitation. In underlining this argument, Hahn points to the recently rechristened Pittsburgh Opera performance space, now called the Bitz Opera Factory. Though the name is partially a nod to its former use as a Westinghouse air brake manufacturing plant, “I firmly believe what we do is make opera,” says Hahn. “The fact that it was composed 200 years ago doesn’t mean we aren’t making it all over again.”

This article was published in the Spring 2022 issue of Opera America Magazine.

Sophia Bennett

Sophia Bennett is the editor of Opera America Magazine.