Rising to the Challenge

How music schools navigated the pandemic.

Balancing students’ need for a robust education and a safe place to learn and live has been a difficult dance for music schools over the past two years. Many of the adaptations instructors and administrators made during the COVID-19 pandemic led to long-term changes that will improve instructional delivery.

In “normal” times, many voice instructors would have eschewed the idea of teaching at a distance, says Allen Henderson, executive director of the National Association of Teachers of Singing. “A majority of teachers viewed that as a ‘less than’ option,” he noted. But when conservatories were forced to move to online instruction, many found it worked better than they expected. To their surprise, some discovered they preferred teaching online, both from a pedagogical perspective and because of the flexibility it provided. Instructors could coach students who were performing remotely, do more traveling and performing themselves, and even expand their businesses to take on clients in far-away locales.

Stuart Skelton, chair of the opera department at the University of Cincinnati’s College-Conservatory of Music (CCM), is currently performing in Germany, something he could not do if he were required to be on campus every week. He’s been pleasantly surprised with the experience of teaching online. “It forces a certain level of concentration that you may not have in person,” he says. Students know their hour with him is the only time they’ll see him during the week, so they set goals for that time and are more focused on meeting them.

The Curtis Institute of Music already held up teaching, touring, and technology as its three pillars of the Curtis experience. But the pandemic pushed the school to transition from a more traditional understanding of these ideas to one better suited to the modern world, says President and CEO Roberto Díaz. “We are rethinking, at the very highest level, what a professional career can look like. It’s not a onedimensional approach, but considering a more diverse set of musical experiences and being mindful that technology is an incredibly important part of a musician’s life.”

On the teaching front, Curtis has reassessed who it can add to the faculty. It recently hired the cellist Gary Hoffman, who lives in Paris and does most of his concert work in Europe, as a part-time instructor. “He can teach some of the students online, and he’ll come to Curtis a few times a semester and do mini residencies and teach chamber music,” says Díaz.

The school’s long-running Curtis on Tour program, which takes musicians into various communities, offered great learning and promotional opportunities for the school but was capped by the physical limitations of travel, Díaz notes. During the pandemic, the school has expanded the program exponentially through technology by making performances available online.

The technology piece is bringing an evolution in how and when classes are taught. “We realize there are certain musical studies or liberal arts classes that can happen in a hybrid model. You have some sessions where people come together and some of the work can be done at your own pace and on your own time,” says Díaz. “In the future, there may be opportunities for an incoming student to do some classwork over the summer,” which would make for an easier adjustment once they arrive on campus.

Technology is also giving students greater exposure to tools they’re likely to encounter in the modern workplace. The vocal studies department (led by bass-baritone Eric Owens) produced a film called MERCY, a reimagining of Mozart’s La clemenza di Tito, created by the writer-director team of Chas Rader-Shieber and Alex Shrader. “If you’re fortunate enough to land a role at the Met, you’ll be singing in front of cameras,” Díaz points out. “To have that experience while you’re still in the more ‘safe’ environment of school is a huge plus.”

While the Jacobs School of Music moved many things online, it prioritized keeping performances in person — and managed to present five of the six operas it would typically stage in a season. “We realized the most important thing for our students is to learn roles and perform them from top to bottom,” says Jeremy Allen, the school’s interim dean. “That’s what gives them the experience they need. That can be done in all manner of different settings.”

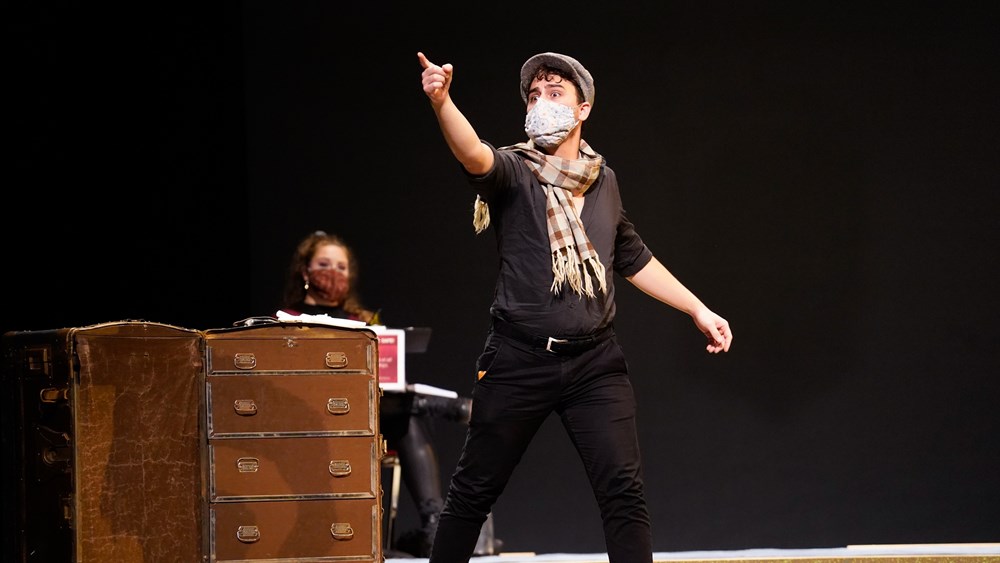

Opera rehearsals moved outside for much of the school year. The school’s costume shop made special masks that allowed singers to drop their jaws and not have their masks fly off. Stage performers were not allowed to stand within 10 feet of each other, which became an interesting teaching point. There were frequent conversations about “understanding physicality and how the use of your body is important to communicating to the audience what is going on,” says Associate Professor of Music Michael Shell, who leads the Jacobs School’s opera program. It was a challenge artistically but gave the students a deeper understanding of body language and stage intimacy.

Students also learned many lessons about creativity, flexibility, and professionalism. “I said to the casts, ‘This is training for your life. When you go out and do that job, you can’t afford to be sick. You can’t afford to not be at your best at every rehearsal,’” says Shell. “They now see the value in taking care of themselves in those production weeks.”

The same care they take of themselves, they extend to others, he adds. “I can see it in their attitude and the way they’re committed to ensuring each other’s safety.”

Skelton in Cincinnati hopes faculty will never need to make a sudden pivot like this again, but “it’s nice to know that when we really needed to, everyone at CCM was of one will to make sure we were doing everything we could to keep everyone safe and to ameliorate, where possible, the impact on students.” He, too, has been impressed with how students have risen to the challenge. “There’s very much this attitude of, ‘This is the hand we’ve been dealt, let’s play that hand and get on with it.’ It shows dedication and resilience. As a teacher, that’s incredibly inspiring.”

This article was published in the Spring 2022 issue of Opera America Magazine.

Sophia Bennett

Sophia Bennett is the editor of Opera America Magazine.