Where There Never Was a Hat

An Appreciation of Stephen Sondheim

When I first began writing opera librettos some 20 years ago, I’d never heard of Francesco Maria Piave, Arrigo Boito, or Pietro Metastasio. Any knowledge about the power of words and music to tell a story I acquired as a musical theater lyricist who studied — rather fanatically, like many of his devotees — the work of Stephen Sondheim. And it wasn’t Figaro or La traviata or La bohème or any grand production at the Met that inspired me to write opera; it was seeing the original production of Sondheim and author Hugh Wheeler’s Sweeney Todd on Broadway. (Years after that, when I met Steve, who had presented me with the first Kleban Prize, we spoke of his motivation in writing Sweeney Todd. His answer — “I just wanted to scare people” — remains the best and truest artist’s statement I’ve ever heard.)

Sondheim’s mild disdain for opera is well-documented. In his own work, he preferred more of a balance between spoken and sung words than opera typically offers. He also favored the message of a single song over traditional opera’s tendency to deify the singer who delivers that message in virtuosic notes. But most of all, he disliked the labeling of the two musical forms and dismissed it as “a fool’s game.” When asked what distinguished opera from musical theater, he shooed away the question with the answer that operas are performed in opera houses and musicals are performed in musical theater houses.

I believe that much of the rise of contemporary American opera in the last two decades, as well as its success in finding wider audiences, can be attributed to its connection with Sondheim’s musical theater. While many cultural arbiters like to segregate opera from musical theater, it is a fact that most of the contemporary operas that have carved a spot in the modern repertoire with repeat productions can trace their lineage to the narrative-driven format of the American musical. In fact, Paul Moravec, the Pulitzer Prize-winning composer whose operas include The Shining and The Letter, says, “More than simply influencing American opera, to a remarkable extent, Sondheim is American opera.”

Many of my librettist colleagues concur. Lila Palmer, whose work includes American Apollo and Holy Ground, says, “When we talk about music drama in the 20th and 21st centuries, we talk about Sondheim. His influence on the librettists and lyricists of this generation is undeniable, even in Oedipal revolt!” Jerre Dye, who wrote the librettos for The Falling and the Rising and Taking Up Serpents, shares that “Sondheim’s work is not only my bedrock as an opera librettist, it teaches me something about the sublime and how hungry humans are for living life.” Royce Vavrek (Breaking the Waves, Dog Days) told me, “It’s hard to imagine that I’d be writing opera if it weren’t for those days rehearsing ‘Buddy’s Blues’ in my childhood basement. Sondheim’s storytelling was revelatory and foundational.”

Opera composer colleagues wrote similar reflections on Sondheim. “Seeing the opening trio in the original production of A Little Night Music at a very young age was a revelation; it showed me how music could both delineate characters and unite them in the same moment of yearning,” says Scott Davenport Richards (Blind Injustice). “In every opera I write, I aspire to reach Sondheim’s graceful and generous merging of words and music,” says Kristin Kuster, part of the team that created A Thousand Acres. Kamala Sankaram, whose work includes A Rose and Thumbprint, adds, “Sondheim’s work was life-changing for me as an artist. The bridge he created between musical theater and opera taught me the commonality between both.”

Even the next generation of librettists finds inspiration in his work. Isabella Dawis, a performer, playwright, and the lyricist of Half the Sky, says, “As a young lyricist and librettist, I am in constant conversation with Sondheim’s legacy. I often find myself unconsciously striving to emulate, honor, or defy him.”

We can call Sondheim’s works musicals if we define that assessment by the equation of spoken versus sung words. But how laughably reductive it is to apply the word “showtune” to such intricate and sophisticated songs as “Sunday” from Sunday in the Park with George, “Epiphany” from Sweeney Todd, “Bowler Hat” from Pacific Overtures, or “A Weekend in the Country” from A Little Night Music. The music and lyrics of all these songs — and the list is unending — rival the best of Puccini, Britten, Verdi, and Strauss.

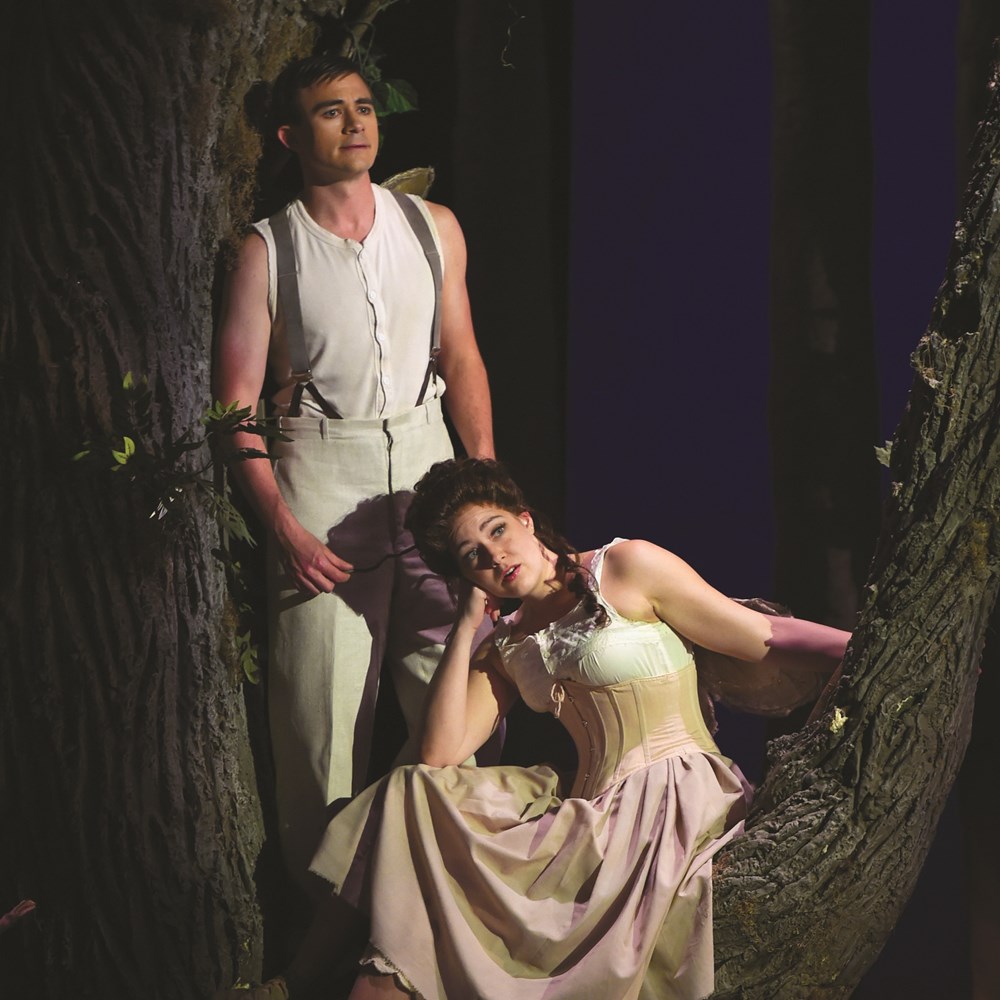

Along with his influence on composers and librettists in the creation of opera, several of Sondheim’s own works have found a secure place in the opera repertoire. Hardly a season goes by when Sweeney Todd is not produced by opera companies in this country (last season at Des Moines Metro Opera; this season at Opera Omaha; next season at Austin Opera). A Little Night Music is not far behind.

Today, when I mentor librettists and composers, I am more likely to ask them to study Sondheim than Von Hofmannsthal. I am also more likely to show them the lyrical and musical techniques used in Follies or Pacific Overtures to tell musical stories, rather than Salome or Lucia. Indeed, not long after Steve died, I was able to shelve my original lesson plans at The American Opera Project’s Composers & the Voice program (where I have served as the librettist mentor for the last decade) and dedicate a joyful hour to showing how methods used in four songs from his and George Furth’s Company could be applied to opera.

Opera is richer because of the art form Sondheim never fully embraced — and probably even richer because he never fully embraced it. The craft he applied whenever he made a “hat” — “where there never was a hat” — will inspire many generations to come.

This article was published in the Spring 2022 issue of Opera America Magazine.

Mark Campbell

Librettist and lyricist Mark Campbell has penned the stories for 38 librettos, 2 oratorios, and 8 song cycles. Operas shaped by his libretti have won numerous awards, including the 2012 Pulitzer Prize in Music for Silent Night and a 2019 Grammy Award for The (R)evolution of Steve Jobs.