An App for That

Opera and innovation have gone hand-in-hand since Venice’s Teatro San Cassiano came up with the crazy idea of selling tickets to the public in 1637. In his 1888 patent claim, Thomas Edison wrote that the invented his motion picture technology so “we may see and hear a whole opera as perfectly as if actually present.” In 1976, a Santa Fe Opera performance became the first live digital recording. Yet, despite being an early adopter of electric light, radio transmissions and televised broadcasts, the world of opera has been circumspect in its embrace of mobile applications — commonly known as apps — for smartphones and tablets.

Not that the industry has turned its back on apps altogether. Some companies are finding innovative ways to use them to connect with their audiences. Opera Philadelphia is launching a location-sensitive app in tandem with its upcoming citywide O17 festival. New York’s Prototype Festival offers an app that lets users browse events, listen to live recordings, watch videos and follow festival-related news. And at Lyric Opera of Chicago, the company is addressing long concession lines with an app that enables audience members to pre-order drinks with Uber-like simplicity.

Research by the analytics company Flurry shows that the average American now spends an astounding five hours a day on mobile devices, with 92 percent of that time devoted to apps. Still, some opera companies see apps as offering no clear advantage over mobile-friendly websites — not worthy of the precious financial and staff resources that they would demand. San Francisco Opera, Houston Grand Opera and Los Angeles Opera have all skipped apps to concentrate on their websites and social media channels. Opera Saratoga, which had planned to launch a loyalty-program app, discarded the idea after discovering that many audience members were resistant to the idea of downloading the app to their phones.

“Unless you are building an app that’s going to drive consistent engagement and give an added value to patrons, it’s hard to justify the cost and the time,” San Francisco Opera’s chief information officer, Jarrod Bell, says. “If I want to buy a single ticket or figure out where to park, I don’t want to have to download a whole app just to do that.” When Bell joined SFO in 2013, he inherited an app that essentially served as a mobile version of the company’s website. After Bell spearheaded an overhaul of the website to make it “responsive” — in other words, optimized for tablets and phones, as well as computers — the app seemed superfluous.

“You need a responsive website and you need a Facebook page, but an app isn’t something an opera company automatically needs,” says arts-marketing consultant Ceci Dadisman. “Having one for the sake of having one is not a responsible thing to do in terms of budget or time. Your app has to have a very specific purpose.” In 2010, when Dadisman was director of communications for Palm Beach Opera, she launched one of opera’s first apps, providing ticket access, schedules, artist bios and program notes, among other offerings. The app became a minor sensation: Within weeks, it received 300 downloads from people in 34 countries. But when PBO launched a responsive website shortly afterward, it made the app redundant, so Dadisman saw no reason to pay for the upkeep.

Still, she wasn’t done with the technology. She saw a “specific purpose” in 2013, when PBO mounted its first Opera @ the Waterfront program, aimed at novice operagoers. The concert would be staged outdoors in the middle of the day, so supertitles were out of the question; the initial PBO app, called Opera Live Cue, flashed fun facts and libretto translations to let newbies (and others) track what they were seeing and hearing. “It got people engaged,” Dadisman says. The next year, using a $30,000 Building Opera Audiences grant from OPERA America, PBO offered an expanded version that included ticket services, performance schedules, artist bios and program notes, and streaming music.

“It’s a very personal thing to download an app,” Dadisman says. “If you’re going to do it, the app must be amazingly good. You have to make sure the content is something that patrons not only want, but need.”

Lyric Opera of Chicago saw a specific need when it looked at the long lines for the bar at its intermission breaks, representing not only a hassle for patrons, but a potential loss of revenue. Its very first app, launching next season, will serve the sole purpose of improving access to drinks, allowing members of the audience to place their orders, pay for them and select the bar closest to their seats for pickup. “There is no point to having an app to do all the same things your website already does,” says LOC’s marketing director, Lisa Middleton. “But this app serves a purpose.”

The basic capabilities of Opera Philadelphia’s O17 app include ticketing and an FAQ section. (Yes, you can bring lawn chairs to the outdoor Opera on the Mall telecast.) “It will help people navigate a festival that will be all over the city, reminding people where they need to be, while giving them access to their tickets while they are on the go,” says the company’s communications vice president, Frank Luzi.

But it will also make use of GPS to deliver targeted, timely, location-specific messages. “If you walk by the theater, we can send you a push notification inviting you to our pre-performance lecture,” says Ryan Lewis, the company’s vice-president of marketing. “As you’re leaving the theater, we could ask you to stop by our photo booth and get your picture taken.”

The O17 app is intended not just as an audience resource, but as a way for the company to mine useful anonymous data. “It gives us a lot of potential for learning,” Lewis says. “Do we need to open another bar for the next performance? Do we need to open the venue earlier to accommodate traffic?”

To develop the app, Opera Philadelphia enlisted Aloompa, which specializes in large-scale pop-music events like Tennessee’s Bonnaroo festival. The technology company makes it a point to deliver capabilities out of the reach of websites and social media platforms. By providing audience members with tickets, directions and schedules, its apps reduce the staff’s burden on busy performance nights. If there is a delay or venue change, a substitute performer, or a surprise meet-and-greet, the company can let patrons know instantly.

“I was at an outdoor festival we work with and there was a lightning storm, so they had to evacuate the site,” says Stefany Reed, Aloompa’s business development director. “As I’m on my way to my car somebody asked me, ‘Hey, do you know when they’ll let us back in?’ I asked, ‘Do you have the app?’ I told him it would let him know — and it did. It was that simple, but it’s something you couldn’t do with a responsive site or on Twitter.”

Although there is a price tag attached to developing an app, the process doesn’t have to break the bank. The initial “fun facts” version of Palm Beach’s Opera Live Cue cost roughly $3,000. The performing-arts app developer InstantEncore, with clients including Canadian Opera Company, Fargo-Moorhead Opera and Lyric Opera of Kansas City, prices its offerings to suit organizations’ budgets: For a company with a budget of under $1 million, the price is just $1,000 annually, plus a $400 setup fee.

By using Instant Encore’s platform the Prototype Festival was able to launch its app not only inexpensively, but quickly: The process started just two months before this January, when the app went live for the festival itself. So far, so good — except that Prototype managed to persuade only 82 people, out of an audience of nearly 10,000, to download it. In fact, many InstantEncore products have similar download rates. The risk is clear: Even if an app only costs $3,000 and doesn’t take much time or effort to build, these resources are wasted if only a handful of people actually use it.

But the 2017 Prototype app was only a “soft launch” according to Kim Whitener, the festival’s co-founder. She intends to market the app vigorously for its 2018 outing, starting six months before the festival and touting it on brochures and the Prototype website. “Even people who are very tech-savvy aren’t going to download an app just because it’s there,” Whitener says. “A company really has to push it and make it something people go out and explore. They have to be excited about it to get the public excited about it.”

Palm Beach Opera added pitches for Opera Live Cue to all its promotional materials, promoted the app on Facebook and tagged it in print materials. Not only did the strategy work to encourage downloads, but the app itself generated media attention for Opera @ the Waterfront. “The local ABC affiliate isn’t going to cover the ‘there’s another outdoor opera concert’ angle,” says Dadisman. “With the app, all of a sudden I had an angle to pitch.”

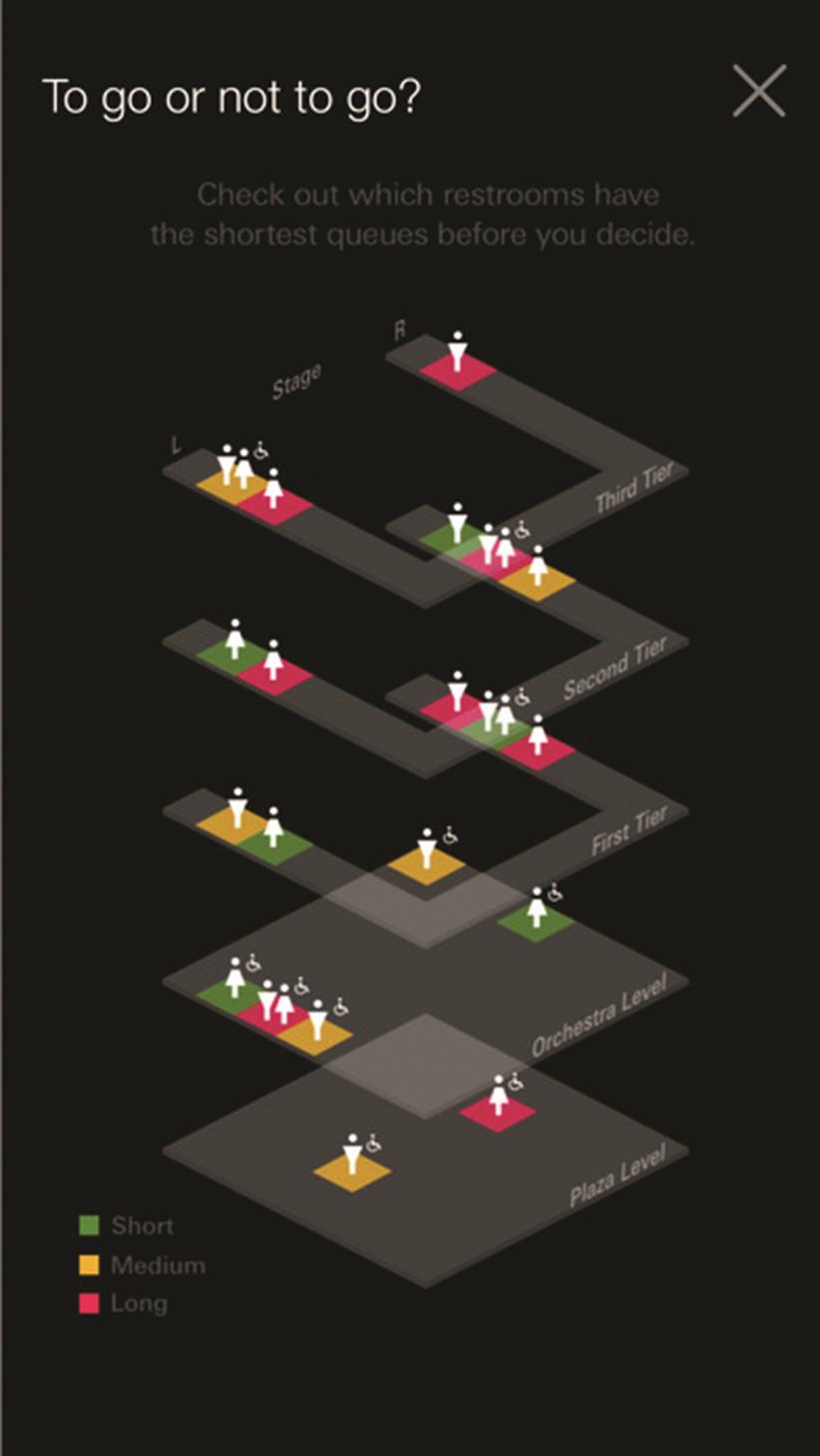

Probably the best way to ensure downloads is to give the audience something it really needs. Lincoln Center’s app, introduced in May 2016, lets users browse the arts campus’ offerings, order tickets, get drinks at intermission — even access a real-time “bathroom tracker” to avoid long waits for restrooms. (Although the calendar function lists all events on campus, only some constituent organizations, like New York City Ballet and the Chamber Music Society of Lincoln Center, have signed on for the full menu of capabilities, with the Metropolitan Opera and the New York Philharmonic being the most prominent holdouts.)

“We wanted to provide user-centric tools,” says Peter Duffin, Lincoln Center’s senior VP of brand and marketing. “We looked at the user experience and thought, ‘How can we improve that?’” If the messages generated by the app’s feedback form can be trusted, the Lincoln Center team is on track for success. A typical comment: “I will be in NYC for the first time next month. Seeing Lincoln Center is on my ‘must do’ list, and this app will make it so much easier to enjoy my time there.”

“When you’re trying to do something in a patron-conscious way, and you get feedback like this,” Duffin says, “it lets you know you’re doing the right thing.”

This article was published in the Summer 2017 issue of Opera America Magazine.

Jed Gottlieb

Jed Gottlieb spent nearly a decade as the senior music and theater critic at the Boston Herald. He has written for Newsweek, Quartz, Columbia Journalism Review, and many more.