Composers Move from Screen to Stage

The way music works with film, and the way it works with staged theater, is not so radically different,” says Laura Karpman. The four-time Emmy winner has long worked in television and film, and she received a 2015 OPERA America Discovery Grant for Female Composers to develop Balls, an opera recounting the infamous 1973 tennis match between Bobby Riggs and Billie Jean King. In straddling the genres of opera and film, Karpman assumes a place in a line that includes Copland, Bernstein, Prokofiev and Shostakovich, along with contemporary composers like John Corigliano, Germaine Franco and Nico Muhly.

“It’s the same impetus for both opera and film,” says Karpman. “You write what serves the story.”

“Film and opera both require the dramatic talent to read a text and say, ‘This is what’s called for,’” says Corigliano, composer of The Ghosts of Versailles and winner of an Academy Award for The Red Violin. “Some composers are dramatic and theatrical, and some are not.”

Muhly points out that some film music has distinct counterparts in the operatic repertory. “Music that works thematically, like in Star Wars or Lawrence of Arabia, is the perfect Wagnerian thing,” he says. “The music knows more than the people: ‘Ooooh ... she’s going to use the Force!’” (His new opera Marnie opens this fall at the Met, and he has also composed scores for movies like The Reader and Margaret.)

Franco, a 2018 recipient of an OA Discovery Grant for ¡La Capitana!, about a soldadera in the Mexican Revolution, intends to bring to the project a folkloric tone similar to her work on the animated film Coco. Just as in that lauded score, she is using indigenous instruments in her orchestration for ¡La Capitana! “I want this be something people in a small village in Mexico could enjoy,” she says. She notes that military bands were a part of the Mexican Revolution, often playing marches by Verdi — an indication that opera in that day was a popular art form much like film is today. “I’m not writing for a higher art form, or just for a certain class of people,” she says. “Let’s make this an opera that people who don’t know anything about opera can enjoy.”

As similar as the dramatic aims of film music and opera may be, the compositional process can be wildly unalike. “The biggest difference is who’s driving the car,” says Muhly. “In a movie, it’s the director. With an opera, the score is the text that will guide everybody’s life for three or four months. Everybody is sitting in a room looking at a document that I, the composer, created.”

“For a composer, opera is at a midway point between film and symphonic music,” says Corigliano. “In film, the composer is like the sound-effects person, serving the director. He will want something, and if you don’t give it to him, he’ll get someone else. In opera, the director can be the prima donna, interfering and making changes. In symphonic composing, nobody lays a hand on it. They promise to play it, whether they like it or not.”

The very fact that they have to take the back seat can make a film project, for some composers, a more straightforward task than an opera. “You’re given so many instructions,” Corigliano says. “‘You’ve got one minute and 13 seconds, and 40 seconds in you need a climax.’ All of this makes it easier to compose.”

“If you look at a page of text you’re going to set as a song or as an opera, it’s difficult to know how long it’s going to take to get through,” says Muhly. “Sometimes you’re running downhill, sometimes uphill — it’s an elastic bungee cord of possibility. There’s no ‘In the next shot, you have 30 seconds.’ That’s the hardest thing with opera — it’s so much more your problem.”

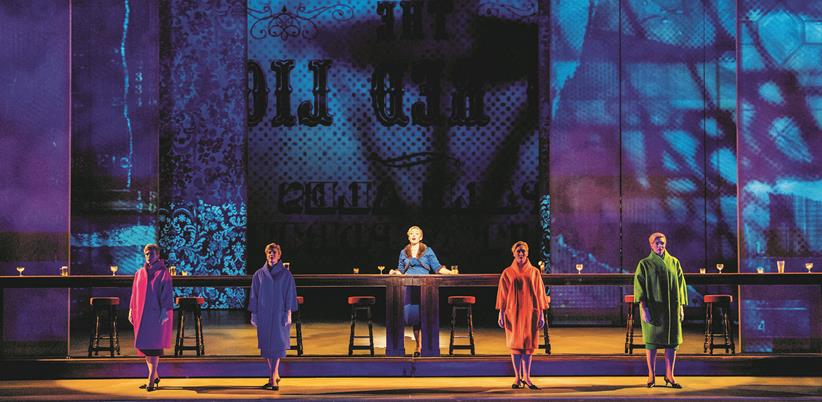

Workshopping is a vital part of the composition process in both genres, Laura Karpman says: Film music may have no formal workshop process, but “you workshop it for the director.” She found something similar when she brought her children’s opera, Wilde Tales (a 2015 OA Commissioning Grant for Female Composers recipient) to The Glimmerglass Festival, under Francesca Zambello’s direction. “She was as tough as any movie director: ‘We have to cut this; we have to move that,’” Karpman reports. “And she was right about every single thing.”

She believes that her grounding in the work ethic of film composition has served as good preparation for her opera assignments. “One of the things I love about doing commercial music is that it’s a daily practice,” Karpman says. “Some of it is going to be special, and some of it isn’t. To be a flexible opera composer, you have to have the same attitude.”

This article was published in the Summer 2018 issue of Opera America Magazine.

Fred Cohn

Fred Cohn is the former editor of Opera America Magazine.