The Year in Review: The Field

Today’s operatic repertoire shows tectonic change beyond established classics,” Robert Marx wrote in the spring issue of Opera America, and this year’s bumper crop of world premieres definitely bears out his observation.

Marx’s essay notes that in the 1983–1984 season, OPERA America’s constituent companies offered but one world premiere. Compare that to the years 2010–2016, in which the organization’s members offered no fewer than 225 new North American works in their debut productions.

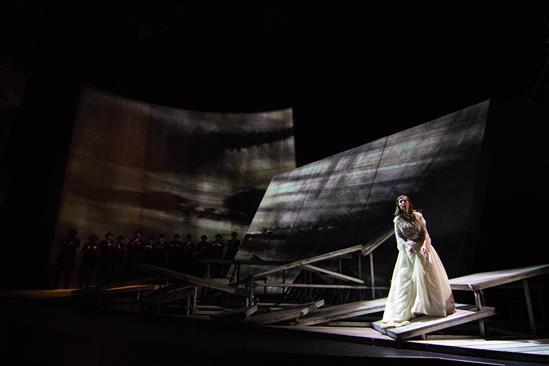

But numbers alone don’t tell the whole story. The field’s attitude toward contemporary opera has also changed. No longer does the presentation of a new work feel like a dutiful chore, tangential to the real business of mounting the standard repertory. On the contrary, operas like Breaking the Waves (Opera Philadelphia), Fellow Travelers (Cincinnati Opera), The Scarlet Letter (Opera Colorado), The Shining (Minnesota Opera) and Sister Carrie (Florentine Opera Company) — among many others — served as flagship productions in their companies’ seasons: generating outsize media attention, attracting donor dollars and bringing new audiences to the art form.

The vitality of contemporary opera can be seen not only in world premieres, but also in myriad revivals of recent works. A common complaint of the not-so-distant past cited the tendency of new operas to disappear from view after their premieres. All the prestige, the thinking went, clung to first productions; after that, the works themselves languished. No longer. In 2016, companies presented second, third — or 47th — mountings of numerous works from recent decades. OPERA America’s accounting of the most-performed operas during the 2015–2016 season included (alongside the expected Madama Butterfly, La bohème and Carmen) Jake Heggie’s Dead Man Walking (nine productions) and his Three Decembers (eight productions). In the past year, Mark Adamo’s Little Women has been staged by Eugene Opera, Madison Opera and Pittsburgh Opera. Kevin Puts’ Silent Night showed up at The Atlanta Opera and Michigan Opera Theatre, and his Manchurian Candidate at Austin Opera. Des Moines Metro Opera staged Philip Glass’ Galileo Galilei and Los Angeles Opera, his Akhnaten.

Of the three works in Opera Saratoga’s summer 2016 season, two were of recent vintage: Daniel Catán’s Il Postino and Glass’ The Witches of Venice. “New works can speak to audiences in a visceral way,” says Lawrence Edelson, the company’s artistic and general director. The box office validated his instincts: The season saw a 35 percent uptick in ticket revenue.

The need for opera organizations to strengthen bonds with their communities has never been more strongly felt — or more thoroughly addressed. Opera is no longer confined to the opera house: This past year it could be found in schools, community centers, libraries, farmers’ markets, and even a basketball court. Companies are proving the art form’s relevance by grappling with urgent local issues: In the wake of the Pulse nightclub tragedy, Opera Orlando staged a benefit concert, “One Voice Orlando.” Addressing the effect of the energy downturn on its community, Houston Grand Opera offered free subscription renewals to laid-off energy-company employees. Lyric Opera of Chicago, in partnership with the Chicago Urban League, is developing a new musical theater work to be written by local youths, based on the city’s epidemic of gun violence.

These trends in no way spell the end of the standard repertoire. The great works of the period between Mozart and Puccini still form the core of the repertory, often in fresh, inventive stagings that serve as reminders of why these masterpieces endure. Wagner’s Ring continues to serve as the ultimate test of an opera company’s mettle: Washington National Opera mounted Francesca Zambello’s familiar Ring production this past spring, and Lyric Opera of Chicago launched a new David Pountney Ring cycle with Das Rheingold. But the Ring is no longer the exclusive provenance of the biggest companies: Both Minnesota Opera and North Carolina Opera offered Das Rheingold as trial balloons for potential complete cycles, to critical plaudits and box-office success. Meanwhile, Sarasota Opera closed out its complete Verdi cycle — a monumental, 28-year effort — with Aida and the rarely heard La battaglia di Legnano. Innovative approaches to repertoire, along with the ever-increasing role of community engagement in company endeavors, reveal a field no longer willing to settle for business as usual — and one that’s connected to the world at large.

This article was published in the Winter 2017 issue of Opera America Magazine.

Fred Cohn

Fred Cohn is the former editor of Opera America Magazine.