A Life in Opera: Q&A with Charles MacKay

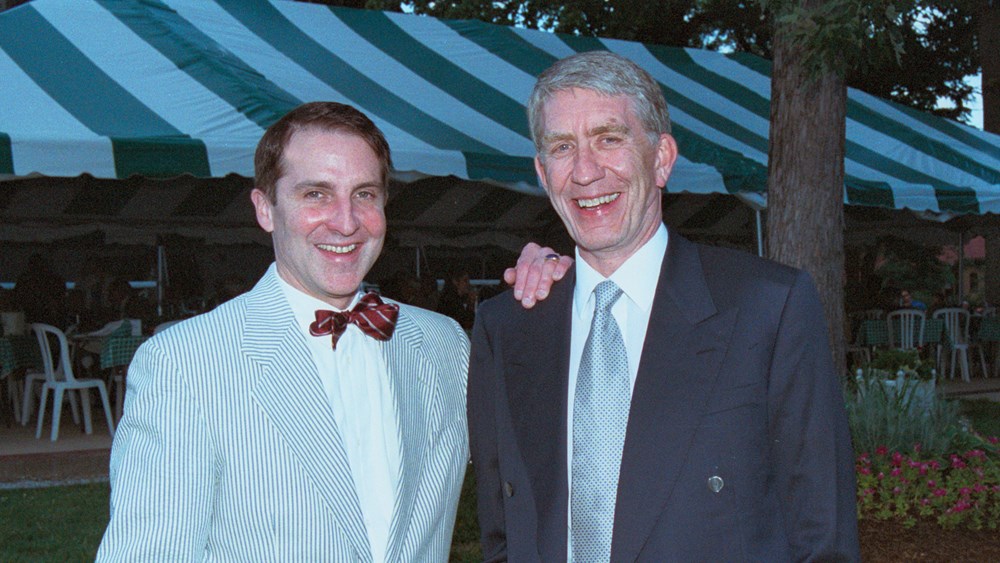

Charles MacKay, who retired as general director of the Santa Fe Opera in 2018, talks to Marc A. Scorca about his career at the top in Santa Fe and at Opera Theatre of Saint Louis, and his lifelong love of the art form.

SCORCA: How did you first find opera — or how did it find you?

MACKAY: Well, I think it found me in the womb. Both my parents were big opera lovers. They were very fine amateur singers, they played opera recordings almost constantly, and they listened to the Met broadcasts every Saturday. So I think those vibrations were with me practically from inception. I went to my first opera, Die Fledermaus, in 1959, when I was nine years old. It was the first-ever youth opera presented by the Santa Fe Opera. I was mesmerized from the very moment that the performance began. I made my parents get me my own little portable phonograph player and a recording, which I must’ve worn out. They were probably thoroughly sick of Die Fledermaus by that point.

I started going to the youth nights every summer. My parents were quite scandalized by some of the operas that were selected, like Honneger’s Joan of Arc at the Stake and Salome, which the eight- to ten-year-olds in the audience loved — especially when the head came up at the end. My first direct involvement with the Santa Fe Opera was when I was 13 years old and I was a volunteer parking attendant. We were allowed to stand in the back of the theater and watch the performance. I think most of the other kids were out in the parking lot smoking cigarettes, but I relished the opportunity to see the performances. And of course this was in the company’s original theater, which was a much more intimate space.

That’s the theater that burned down.

In 1967. How vividly I remember that day! We were all terribly upset, but [company founder] John Crosby organized things so that the season could continue uninterrupted at the high-school gymnasium. He mobilized the whole company to build platforms and makeshift scenery. And he immediately set out to raise the money to rebuild the theater. Support started to pour in, in the form of $5 and $10 contributions for the rebuilding fund. Remarkably enough, the new theater opened the next year, 1968, which was my first season working for the Santa Fe Opera. It more than doubled the seating capacity of the original theater. And it also provided for a proper scene shop, a small costume shop and some practice rooms. So in many ways, the fire was a blessing for the company, helping it to gain a larger national and international profile and also to garner support from around the country.

And to be ready for your own arrival on the scene as an arts administrator on the rise.

The story is this: I was an aspiring French horn player at that time, in my senior year of high school. I decided, because I was first chair in both the All State Orchestra and the Santa Fe Symphony, that by golly, I could play in the Santa Fe Opera orchestra. Never mind that they were all professionals and I was a rank amateur. I pestered the life out of John Crosby’s secretary and I was granted a 15-minute interview.

I took off from school, wore my best Sunday suit and drove my mother’s Buick Roadmaster to the opera offices, bringing my horn with me. I was ushered up to Mr. Crosby’s office. He was sitting there surrounded by stacks of paper, chain-smoking, looking at me squinty-eyed over the tops of his glasses. I said, “I would like to play the first movement of the Mozart third horn concerto.” I think he was astonished to have this kid propose to play for him, but he sat back and listened. Well, you have to empty the slides of the horn, lest it gurgle while you’re playing. So I pulled out one of the slides and I was turning the instrument upside down, and all of a sudden everything went into slow motion — like I’m watching a movie of myself emptying my spit onto the carpet of the general director of the Santa Fe Opera’s office. I wondered if that was really a good idea. But I gathered myself and continued. When I got to the end of the first movement, I looked at him brightly and said, “Would you like to hear the second movement?” And he said, “That won’t be necessary.”

I proposed playing in his orchestra. He said, “Well, I don’t make those decisions,” but I got an audition with the principal horn. I’d memorized all of the famous operatic horn excerpts. I played the opening of the third act of Tosca, the opening of Der Rosenkavalier, the Fidelio overture and the opening of Micaëla’s air from Carmen. He said, “I think we could actually use you as an extra player for the offstage banda in Der Rosenkavalier this summer. Your main duty, however, will be as an orchestra assistant: setting up the chairs in the orchestra pit, putting out the music, sweeping out the orchestra pit after every performance and keeping track of all the music.” And so I was the “pit boy.”

OPERA America was founded two years later. What wafted through the ether to you about this new organization?

I started working full-time for the Santa Fe Opera in 1971–72. My title was “administrative assistant and fund-drive clerk,” but John was always giving me new assignments. Sometime in the mid-70s, when he was president of the organization, he hosted a board meeting of OPERA America in Santa Fe. I was the gopher, making sure that everyone had tickets and that the room was properly arranged for the meetings. Then I went to the reception and met all these famous people. They were very friendly to this kid who was hanging around, and they seemed to be having a good time. I remember that John got absolutely furious on a couple of occasions with some of his colleagues on the OPERA America board. But he was given to mood swings, so that wasn’t unusual.

In 1984, I took over at Opera Theatre of Saint Louis, and soon thereafter I was elected to the board of OPERA America. I probably wasn’t ready to be on the board. I was a freshman general director, but it was a great opportunity for me, and I loved getting to know people.

You have an interesting slant on the industry because you’ve worked exclusively at festivals. If you could roll the dice again, would you want to run a more conventional opera company with a standard season?

For me, festivals were the right fit. They have many advantages, but for every benefit there is a detriment. Festivals rarely can rely on the local audience; they need to be able to attract a national or international audience. That puts a lot of pressure on the general director to formulate a repertory capable of drawing a festival audience.

Opera Theatre of Saint Louis has a big local audience. Was the out-of-town audience really a tipping point to success for Opera Theatre?

Very much so. The Saint Louis audience really sat up and took note when they saw that people were coming from around the country, and that the work that was being presented was important enough to draw a national press. Patrons took tremendous pride in seeing the reviews in national and international publications. When I called on corporate leaders in Saint Louis for support, I would often hear the refrain “I’m not particularly an opera fan, but the fact that Opera Theatre is being reviewed in The New Yorker, in The New York Times, in the Wall Street Journal, in the London Times is tremendously important.”

Young artists have been another through-line for you, both in Saint Louis and Santa Fe.

At the very beginning of my career, I was able to observe at close range the activity of the Santa Fe apprentice program. Frederica von Stade was singing small roles and then of course became one of our superstars. We did a tally at the time of my retirement and found that during my tenures as general director of the two companies, there were something like 432 debuts by singers and some very prominent names. Susan Graham made her debut in Saint Louis 31 years ago, fresh out of the Manhattan School of Music, singing Erika in Vanessa. That production really catapulted her to stardom.

I think back on my life in opera and how I was given a chance by John Crosby and by Gian Carlo Menotti in Spoleto and by Richard Gaddes, who encouraged me to succeed him in Saint Louis. It made me aware of how important it is to provide opportunities for young people.

When you look over the decades of your career, how has the production of opera evolved?

I remember that in my first or second summer in Santa Fe, I was drafted to leave the orchestra and paint scenery for a production of The Marriage of Figaro designed by Allen Charles Klein — a very beautiful, traditional period production. It was so heavy and cumbersome that you couldn’t do The Marriage of Figaro in those days with only one intermission. There were three intermissions, and it required moving a heavy bunch of scenery around on the stage and having a 20- or 30- or 40-minute intermission. So it lasted until 1:30 a.m. I don’t think audiences would stand for that today.

When I first started going to Santa Fe, the curtain time was always nine o’clock. And that’s why a Marriage of Figaro would last until 1:30 in the morning.

That was something I focused on when I returned to Santa Fe as general director in 2008. I asked a lot of longtime friends and donors from my Saint Louis years to come out, and they’d say, “Charles dear, we’re getting up in years and we just can’t do those late evenings anymore.” And then the people who lived in Albuquerque would complain that they’d get home at two or three in the morning. If you had to get up and work the next day, it was just impossible.

So I announced to my colleagues that we would be starting earlier. And they said, “Well, that’s absolutely impossible. We can’t do that because it doesn’t get dark in the summertime until 9:00 p.m.” And I said, “Well, we just have to speak to the directors and designers.” And to my amazement, the directors and designers were on board from the very get-go. I understood that the lighting would be different at twilight. But that can be used very effectively for productions. When you’re sitting in the theater and you can see the sunset and the darkness following the silhouette of the Jemez Mountains in the distance, it is so beautiful. That sense of place, that gorgeous outdoor setting is unique in the world of opera. The sun is setting, the orchestra is tuning and you are going into the world of Mozart or Strauss or Puccini.

It’s not just about making the audience happy, but it becomes part of the aesthetic of the opera performance.

Absolutely. And in Saint Louis, it is such a wonderful thing that people gathered before the performance under the tent or at the pavilion. You can enjoy this beautiful garden setting and have a nice meal and a glass of wine before you go to the opera. And unlike most places, where the artists just want to get out of their makeup and go home, in Saint Louis, they get dressed in civilian clothes and go to the tent and mingle with the audience.

What kind of advice do you offer young people who are looking at careers in opera administration?

People who are starting careers in opera often say, “You must have had your sights on being a general director from the time you were just starting out.” And I always say, “I did not.” I never had any kind of a blueprint; I was just grateful because I loved this art form so much. It was a great gift for me that John Crosby gave me assignments that helped me develop professionally — everything from marketing and development to artistic administration to personnel management. My operating premise was simply to do my assigned task as well as I possibly could, no matter how long it took, and the reward came from knowing I had done my best.

This article was published in the Winter 2020 issue of Opera America Magazine.

Marc A. Scorca

Marc A. Scorca is the president/CEO of OPERA America.