Words, With Music: The Supertitles Revolution

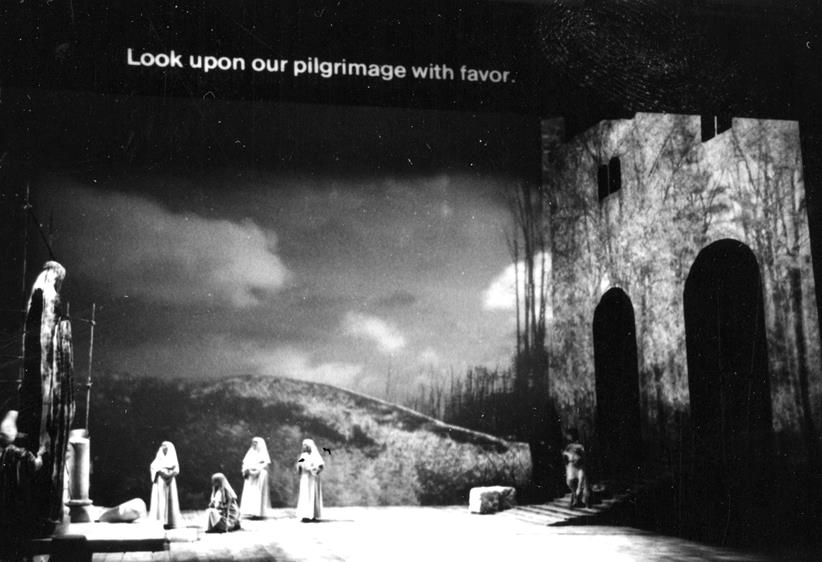

The introduction of supertitles in the mid-1980s transformed opera in America. The Canadian Opera Company pioneered the technology with a 1983 Elektra; a few months later, New York City Opera used supertitles for Massenet’s Cendrillon. Within a short six months, the concept spread to over 100 American opera companies. A NYCO audience survey found a 96 percent approval rating of surtitles.

Speight Jenkins, then general director of Seattle Opera, was in the audience at that Toronto Elektra. “I went to Canada thinking it was just something crazy,” he confesses. “It took me less than three minutes to realize, ‘My god, this is the future!’” He brought supertitles to Seattle for a 1984 production of Tannhäuser.

“Supertitles are the largest single factor in making opera successful in the late 80s and afterward,” Jenkins says. “It brought a whole group of people to the opera who didn’t go before — specifically businesspeople in their 40s and 50s. Before, they did not like to come to something like Trovatore or Ballo in maschera and be lost. With Wagner, it made all the difference in the world. Prior to 1983, everybody thought that Wotan’s monologue [in Die Walküre] was boring; now nobody does.”

The original supertitle system used a carousel slide projector. “The machine was vulnerable,” says Roger Pines, dramaturg at Lyric Opera of Chicago. “Some operas had as many as 989 slides. They could get jammed, and scratches would make them unusable.”

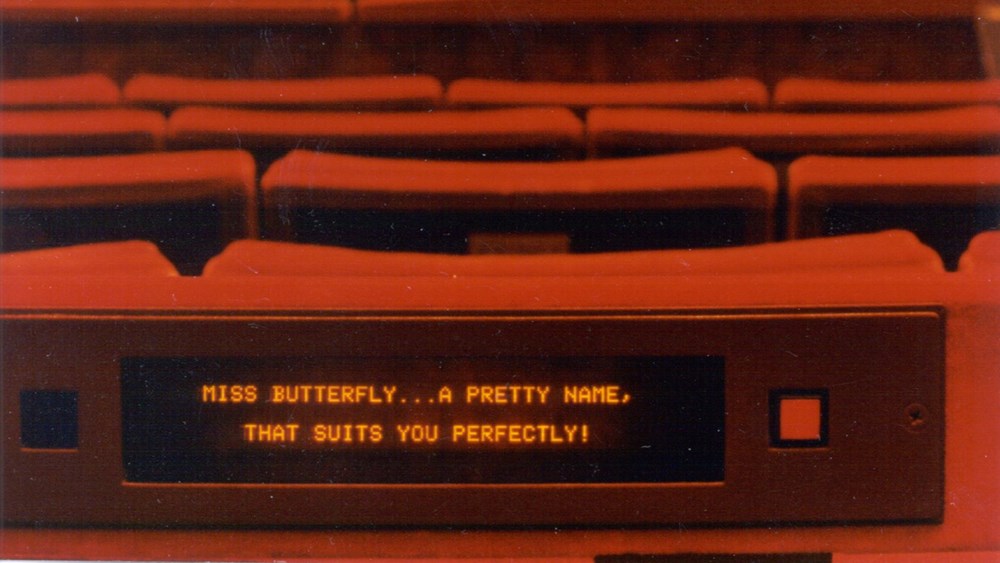

The Metropolitan Opera famously resisted supertitles, but introduced its trademark back-of-seat “Met Titles” in 1995; in 1998, the Santa Fe Opera installed a similar system in its newly built opera house. Elsewhere, supertitles are ubiquitous, generally employing sophisticated computer technology rather than the carousel trays of yore, while still needing personnel to run them in real time.

As a result of supertitles, audiences have now long been able to go to the opera without doing homework beforehand. Still, Jenkins wonders if something has been lost. “It takes away, in a strange way, from the singing itself,” he says. “People are paying attention instead to the text. It has made opera a theatrical rather than a vocal form.”

This article was published in the Winter 2020 issue of Opera America Magazine.

Nicholas Lord

Nicholas Lord is OPERA America's institutional giving manager.