Opera's Digital Future

No one doubts that digital performances saved the moment when the pandemic brought everything to a halt, transforming what felt like the end of the world as we know it into what seemed like the dawn of a new day. But the question that remains is if, or when, the sun will set. How will digital occupy the opera ecosystem going forward?

In some ways, the digital future is already here. Companies have scheduled new online premieres and integrated virtual offerings with in-person performances in their resurrected seasons. They are cashing in on the investments they made in equipment and training and building relationships with their newfound patrons across the globe.

Perhaps most notably, they are indulging the artistic awakenings that occurred when they broke down the barriers that defined how opera was produced for four centuries and realized there were novel and seemingly limitless ways to create the art they love. Opera makers, it is fair to say, are reveling in their success as innovators and eager to deliver more.

The other side of the bitcoin is that digital operas remain expensive to produce and generate limited revenue. They can be less polished than opera house fare, and producing them taxes human resources.

Then there’s this: No one claims that digital content comes close to providing the social value that makes live art crucial to community well-being. But while most opera companies don’t see themselves pivoting entirely to digital, they can see it continuing to be an important part of their toolbox — one that helps them meet business and creative goals.

"I Don't Think We're Going Back."

In some ways, it would be hard to slow down the fast-moving train that digital has become at companies like San Francisco Opera, which is tallying up the pluses and minuses of 20 months of “twists and turns and course changes and corrections and endless negotiations and plans A through ZZ,” as Director of Innovation Programs Lee Helms puts it.

The company entered the forced digital landscape gently, loaning its chorus to a citywide singalong of “I Left My Heart in San Francisco” featuring Tony Bennett. Then it offered a few “digital magazines” with singers presenting select arias interspersed with interviews and appearances from its staff.

San Francisco was fortunate to have a technical head start on other companies. It has been in the digital business since 2007 and already had equipment — updated during the pandemic, thanks to a generous donor — and that set it on a speed course.

It inaugurated the North Stage Door podcast, a clever, behind-the-curtain look at the company’s operations. “I’ve always been of the opinion that the day-to-day happenings of an opera house like ours easily rival any reality show on Bravo,” says Helms, explaining the concept.

Then it went after a finer sort of art, introducing Atrium Sessions, short and intimate solo concerts filmed in its Taube Atrium Theater, and In Song, an ambitious series that traveled to the home turf of singers who presented songs that inspired their careers. Among the performers were J’Nai Bridges, Pene Pati, Jamie Barton with Béla Fleck, and Arturo Chacón-Cruz.

Helms says the company learned to make programming that stands on its own “in a bespoke way that is not meant to make up for something else.” While it has returned to streaming its live performances, digital content is no longer automatically connected or limited to what happens on the opera house stage.

He does not see a scenario where the return to live performance causes digital’s demise. As with other companies, audiences tuned in internationally, and the company wants to serve and maintain its new customers. “We learned that to stay engaged with the greatest amount of people, you have to not only do what you do with brickand- mortar but also pursue audiences in a digital way,” he says. The experience “changed our relationship 100 percent with audiences,” helping them think of opera companies not as remote purveyors of high art, but as people who will be there when you need them, and who will deliver the goods in evolving ways — even right in your living room.

It’s safe to say, as Helms put it, “I don’t think we’re going back.”

New Roles and Skills for Staff

Many in the field believe that digital experimentation changed opera making fundamentally. People learned new skills and built partnerships that are set to last for years.

Companies learned they were more nimble and versatile than they ever imagined. Haymarket Opera Company, headquartered in Chicago, made a shift with relative ease, according to General Director Chase Hopkins. After canceling its 2020 season, the company considered making digital versions of the postponed titles it had slated for the rest of the year. Instead, it decided to let go of everything planned and start fresh.

Haymarket Opera partnered with a film production company and, within two months, began to craft an all-Handel video season, drawn from some of the composer’s shorter works. “We felt it would be a better match for people’s bandwidth to watch online,” says Hopkins. The season included videos of Acis and Galatea, Apollo e Dafne, and Orlando and featured singers working in front of projections with occasional cuts toward the live orchestra.

The shift was transformational and provided tremendous professional development opportunities for the staff, who suddenly found themselves taking on titles typically reserved for movie crews. Garry Grasinski, for example, who had produced the company’s promo videos and archival recordings, was dubbed “film director” and went on to helm all three productions. “It was wonderful to see members of our team step up into other positions,” Hopkins says.

The technological changes also brought the company closer to its mission of presenting accurate recreations of historic operas. Handel’s librettos, for example, call for several very specific backdrops that most companies cannot possibly afford to recreate for large opera house stages.

But Haymarket was able to afford to have Chicago artist Zuleyka V. Benitez make small versions of the scenery, which could be photographed and projected behind singers, appearing as if they were the actual stage size.

Now, the company is inspired to move ahead and conceive more projects developed specifically for digital. “We’ve made new friends with new tools and found new ways of sharing our work through this experience. That is huge,” says Hopkins.

He is attuned to the fact that the company must face a different kind of music: money. Digital productions require sizable budgets — Haymarket’s Handel offerings cost about as much to make as a typical live production — but it is far from certain whether people will eventually be willing to pay for them. It’s also not clear whether audience demand will continue, especially when folks are not spending so much time at home.

A New Art with New Opportunities

Others would argue the opposite. The creation of digital content allows opera companies to occupy and capitalize on cultural spaces that were previously off-limits and reach modern audiences in the ways and places where they want to go for entertainment, whether that be at home or outside of a traditional theater.

Arizona Opera’s film The Copper Queen earned bookings into regional movie theaters and was accepted into the Toronto International Women Film Festival, where its director, Crystal Manich, won the Best First Time Female Filmmaker award.

With music by Clint Borzoni and a libretto by John de los Santos, the opera — a period ghost story set in a historic Bisbee, Arizona, hotel — was supposed to premiere live on stage in September 2020. When the global lockdown took

hold, Manich, who had very little experience in film, turned it into a full-blown movie, nearly two hours long and full of film effects. Aerial shots, extreme close-ups, and multi-angle camera work allow a level of intimacy, and, in this case, sensuality, that would have been impossible with stage presentations.

Arizona Opera worked with the Phoenix-based production company Manley Films as it reconfigured existing set designs to accommodate cameras and remade costumes so their details would look good when projected larger-than-life on a screen.

Cast and crew picked up new skills as they worked in rehearsals to develop character and vocal delivery — and lip-synching abilities — as the production moved toward five days of actual filming, followed by editing that brought the pre-recorded music and visuals together.

“We wanted to keep the theatrical approach even though it was a film,” says Manich. “We wanted to make sure we kept a style that was reminiscent of how you might have seen this in the theater.” For example, light cues changed noticeably the way they do in a live venue. “It’s really a hybrid production that we came up with. And I am really excited about the result.”

The quality of art in The Copper Queen is a good argument on its own for the future of digital, but Manich believes video may also be the key to opera’s future. People flock to movie thrillers, so why not give them more products with the potential to change their idea of what opera is? “I’ve really been advocating for a long time that opera would benefit from digital projects, mostly because it seems to be the way that we could get younger audiences interested in opera and get rid of the stigma of what it is to go to the theater,” she says.

Manich can envision a future where new works are commissioned solely for digital venues, like movie theaters and television, with no intention of putting them onstage. “Once we say the art form is no longer locked into one thing, then we start to expand it and let it grow,” she says.

But can opera actually make that leap?

“For me, the goal is to open up the minds of people who are key players in this industry and say, ‘This is an option, this is a possibility,’” she says. “Not to replace the stage but to really augment what we are offering to people.”

Does Digital Take Away from the Audience Experience?

Washington National Opera had a leg up over its peers in terms of financing the sudden demand for digital products because of its Fund for Innovation and Excellence. That allowed it to take a multi-pronged approach to online productions.

The company continued its existing series of concerts from ambassadors’ residences, though virtually, with ambassadors appearing onscreen to introduce singers who performed in remote locations. It produced an original production called Monuments of Hope, a video tour of nearby national monuments. Accompanied by J’Nai Bridges and Ryan McKinny, the solemn piece was meant to explore the “collective echoes and needs of the American people during a health crisis that coincided with racial strife in the wake of the George Floyd murder.”

Staff made an audio recording of the postponed premiere of the opera Blue, which was in dress rehearsal when the lockdown started, and will release it in the spring. With plenty of downtime, a few orchestra musicians even created customized birthday greetings for major donors.

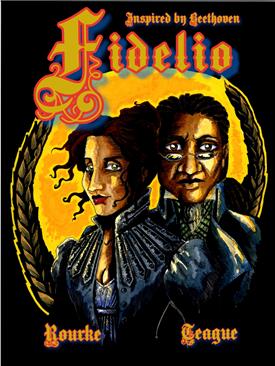

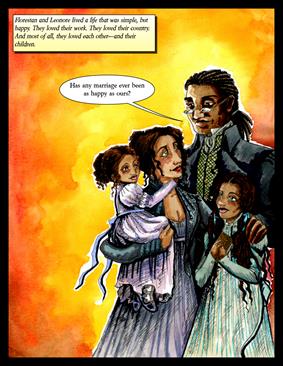

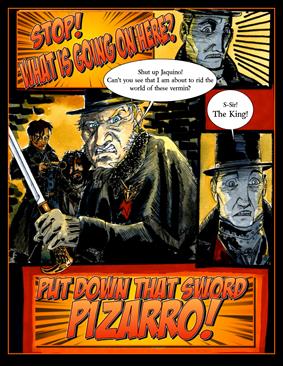

Washington National Opera also explored more innovative offerings. It produced an evocative graphic novel of Fidelio, which features apprentice singers performing over a series of comic book sketches. It’s now finishing up a virtual reality version of two scenes from that opera. The special effects can be experienced directly with headsets or remotely using a mobile phone app, and the plan is to introduce it simultaneously as a live event and digitally via the web.

Despite WNO’s success, General Director Timothy O’Leary has found the conversation around digital performances has led to some soul searching. Do opera companies really want to promote digital as a priority to audiences, artists, and donors when they have always stood for the value of bringing the community together physically?

“Why do we have art? One reason is because it strengthens our civic fabric, because people find they are moved by the same things, for the same reasons, especially if they experience it together in a single space,” he says. “Digital can become an expansion of what we do. But the ancient technology of the flow of energy between audience and performer hasn’t been improved upon.”

A New Way of Thinking

For some companies, digital has provided a game-changing opportunity to connect with audiences in a new way — and establish themselves on a bigger stage. Boston Lyric Opera embarked on its new future by committing to a filmed production of The Fall of the House of Usher. The title was already on its in-person season, which was canceled, and singers and production staff were hired, so that was a natural.

But it thought first about creating systems that would allow it to be “additive” to the world of digital programming and not just another company churning out filmed versions of warhorses, says Acting General and Artistic Director Bradley Vernatter. The result was Operabox.tv, a streaming service. The company recognized digital consumers are attracted to shorter, episodic offerings of video content. Boston Lyric Opera produced a series of hour-long conversations on race, titled We Need to Listen, followed by RETRO+ Short Cuts, which presented audio recordings from its archives visually enhanced with still photos and found video footage.

Its most innovative move was to develop an episodic dramatic series titled desert in, which featured a continuing narrative storyline broken into eight parts, each less than a half hour. Like popular shows on Netflix or HBO, the episodes featured different performers, writers, and directors. Viewers clamored for the unusual fare, which has reached new customers in markets near and far. “More than 80 percent of Operabox.tv subscribers are new to us,” says Vernatter, also noting that content has reached people in 25 countries.

The company is plunging ahead with digital programming, currently wrapping up a full-length version of the composer Ana Sokolović’s Svadba, filmed with a full cast and production crew. That will premiere on Operabox.tv in the coming months. Now, it is thinking bigger, hoping to offer the Operabox.tv format to other cultural organizations in the region, who could use its “space” in the same way the Boston Symphony Orchestra allows others to use its symphony hall.

In some ways, it gives Boston Lyric Opera, an itinerant company that has always bounced around venues, a home of its own just like the big orchestra in town. “The digital space has the power to give individual arts organizations agency they didn’t have before,” says Vernatter.

That argument that digital levels the playing field for small companies also drives White Snake Projects, another Boston-based producer. If prices are uniformly low and all it takes to enter the performance is a click, why can’t smaller operations compete with established giants?

White Snake Projects, which uses opera to advocate for social justice, moved its entire 2021 season online with a series of newly created short operas that featured digital projections set behind singers who filmed their work in front of green screens. Offerings such as Alice in the Pandemic were both visually compelling and urgent to the moment.

Executive Producer Cerise Lim Jacobs says the company pushed its technical capabilities beyond its limits. “It was transformative not just for me, but for the singers, for the artists, and for the entire technical team,” she says. “All of a sudden, we were not doing art we know, but doing art that we don’t know.”

Creating digital content also created a richer experience for opera fans. The company maintained an ongoing chat on the side of the screen during performances where viewers could ask questions about the production or plot, or talk about how a scene made them feel. “During our virtual operas, the chats are a beehive,” says Jacobs. “There is so much sharing and discussion back and forth between total strangers. They are a fully engaged community,” which the company saw as a huge indicator of success.

White Snake Projects has no plans to go back to a live-only lifestyle. Its next season is already set and will feature two live performances and two digital ones. Jacobs hopes to keep that going indefinitely, but it will require some audience development. She believes so much content was offered at no cost that there is an expectation that online content will remain free forever.

But she’s optimistic companies will be able to maintain it by using the strategies they already know, like donor support. Live opera has never gotten by strictly on the strength of ticket sales, so why expect digital to accomplish that? She has found her patrons see the value of digital as a new artistic form and a way of bringing new customers into the fold.

With that in mind, White Snake Projects offers a multi-tiered pricing system. Some viewers pay top dollar knowing that others, who don’t have the cash or are less willing to spend it, are able to tune in at lower prices. “So the people who pay real theater prices will subsidize all those other people we want to reach who would never set foot in an opera house,” Jacobs says.

Creative approaches to funding online opera performances may be the next place where innovation is needed. Digital has helped opera companies meet many of the goals they already had, including bringing in new viewers, aiding with staff development, addressing critical community issues, and finding new opportunities for artistic expression. It now has a place in the opera world — if it can drive revenue from ticket buyers, donors, or a yet-to-be-imagined form of support.

This article was published in the Winter 2022 issue of Opera America Magazine.

Ray Mark Rinaldi

Ray Mark Rinaldi is a veteran arts writer and critic whose writing has appeared in Opera News, Chamber Music, Inside Arts, and the Denver Post.