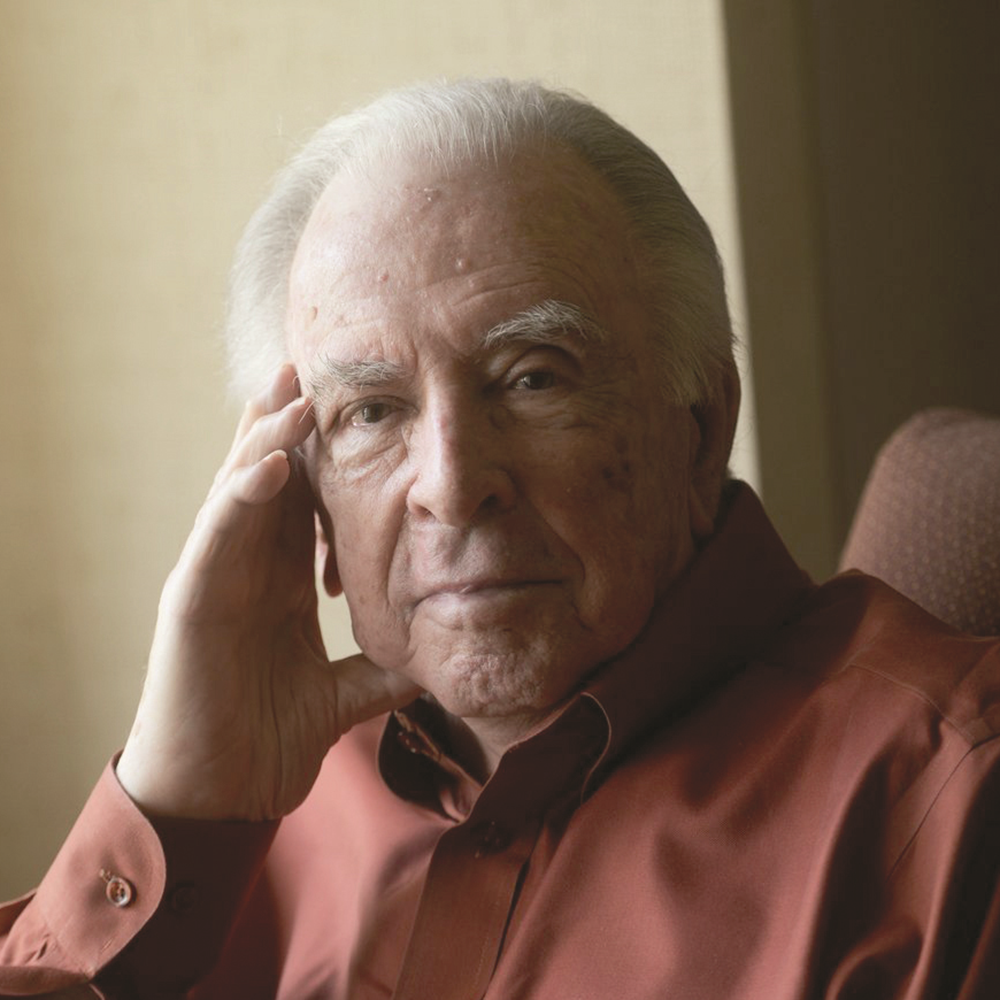

Remembering Carlisle Floyd

Echoing Carlisle Floyd’s first grand lyric effusion, Susannah’s “Ain’t It a Pretty Night,” the polymath genius slipped into his own late evening on September 30 when he died in Tallahassee, Florida. During 95 years of life and creation, he displayed skills in piano performance, creative writing, and visual arts, all before launching himself into America’s 20th-century opera world — with two 21st-century offerings — and becoming its preeminent librettist and composer. His compositional idiom is a highly personal blend of accessible melody, polytonality, and Americana, reflecting the Southern garden bed of his English-Irish-Scottish-Welsh transplantings. As his own librettist, he was America’s avatar of Richard Wagner’s total work of art: words and music by Carlisle Floyd.

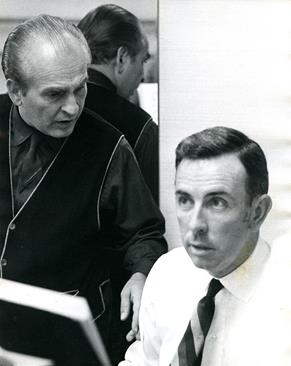

He collaborated with many of the 20th century’s greatest artists. A modest listing includes Frank Corsaro, Phyllis Curtin, Renée Fleming, David Gockley, Mack Harrell, Robert Holton, Jack O’Brien, Harold Prince, Samuel Ramey, Julius Rudel, and Norman Treigle. His generosity to colleagues is legendary. Floyd could always be depended on to help any young artist or artist in crisis. Into his 90s, he mentored such creative talents as Mark Adamo, Matt Aucoin, Jake Heggie, Henry Mollicone, and Rufus Wainwright. “Carlisle was an indefatigable ambassador for American opera,” notes Marc A. Scorca, president and CEO of OPERA America. “He traveled tirelessly across the continent to meet with fellow creators and artists, attend productions of his operas, and participate in panel discussions — warmly and unstintingly offering insights from a lifetime spent in opera.”

Floyd’s American roots were deep and widespread. His first immigrant ancestor arrived at Virginia’s Jamestown colony in 1623. Over succeeding generations, most of the family settled in agrarian regions of South Carolina. Our Carlisle Sessions Floyd — his father, the Methodist minister, bore the same name — was born in the tiny town of Latta, South Carolina, on June 11, 1926, to Reverend Floyd and Ida Fenegan. Floyd and sister Ermine grew up in a whirlpool of family gatherings and visits, summer revival meetings, and frequent moves around the state for their father’s postings — all of it direct source material for Susannah and her operatic siblings.

Floyd’s mother Ida was his first piano teacher. Excepting some potential Welsh bard lost to history, the Irish Fenegans were the font of his music. His first career aspiration was to become a concert pianist. To that end, he studied with such titans as Ernst Bacon, Sidney Foster, and Rudolf Firkusny. Acquaintances with actors, dancers, directors, choreographers, and conductors steered Floyd instead to composition and ultimately to opera. Bacon, also a composer of note, opened the portal to Floyd’s modest operatic debut: Slow Dusk, based on one of the composer’s early short stories, premiered with Syracuse University’s Opera Workshop in May 1949. Its initial success led to 12 new operas over the next six decades; four of these, with substantially revised texts and music, bring the actual total to 17.

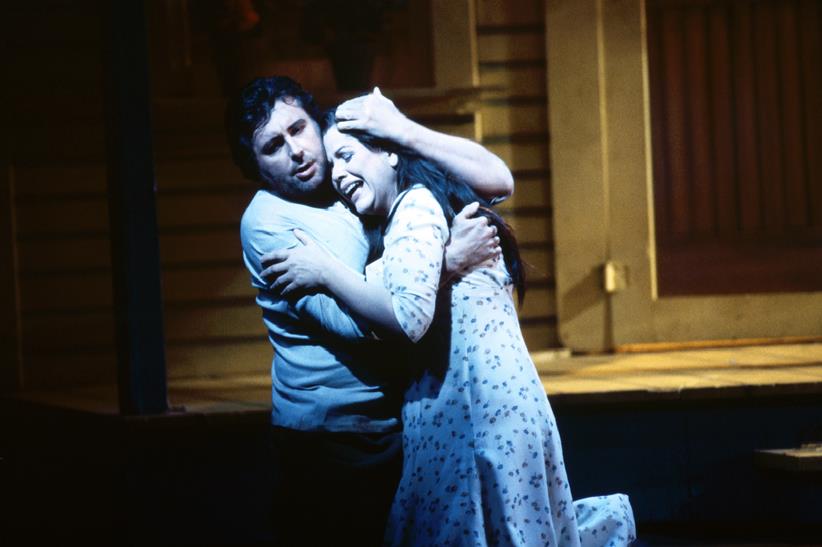

Fugitives, based on another Floyd short story, followed Slow Dusk. After a disappointing production at Florida State University (FSU) in 1951, the composer consigned Fugitives to the relative safety of his collection donated to the Library of Congress. Susannah (FSU, 1955) won Floyd enthusiastic acceptance and eventually international popularity. Beginning its life at The Santa Fe Opera in 1958, Floyd revised Wuthering Heights for New York City Opera the following year. The Passion of Jonathan Wade, a grand Reconstruction-era tapestry, debuted at New York City Opera in 1962 and, in a thorough revision, at Houston Grand Opera in 1991.

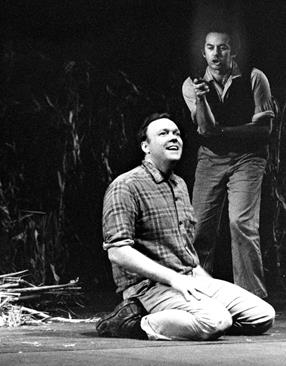

The 1960s also witnessed the creation of The Sojourner and Mollie Sinclair, a one-act tale of 18th-century Scottish immigrants, to commemorate North Carolina’s Tercentenary (East Carolina College, Raleigh, 1963); and Markheim, based on Robert Louis Stevenson’s short story with demonic overtones (New Orleans Opera, 1966). Of Mice and Men, Floyd’s much-revised treatment of John Steinbeck’s novel, found its first home at Seattle Opera in 1970 and quickly became his most-performed work after Susannah. The Jacksonville Symphony premiered Flower and Hawk, a one-act monodrama in the voice of the historical Eleanor of Aquitaine, in 1972.

Floyd’s affiliation with Houston Grand Opera bore Bilby’s Doll (1976), based on Esther Forbes’ Mirror for Witches, a tale of religious persecution in 17th-century New England that was subsequently revised for the Houston Grand Opera Studio in 1991–92. In 1981, Houston mounted Willie Stark, Floyd’s retelling of Robert Penn Warren’s All the King’s Men.

After two decades of personal and professional upheaval, Floyd turned to Olive Ann Burns’ Cold Sassy Tree for Houston in 2000. This return to Southern roots — termed by one critic the first great opera of the 21st century — has become Floyd’s third most popular work. Toward the beginning of 2011, he turned to Jeffrey Hatcher’s play Compleat Female Stage Beauty and its 2004 cinematic adaptation, Stage Beauty, for the story of his next opera, Prince of Players. Its Houston premiere in March 2016 elevated Floyd, just weeks before his 90th birthday, to the ranks of such late-life composers as Claudio Monteverdi, Giuseppe Verdi, and Richard Strauss.

Floyd simultaneously enjoyed a distinguished teaching career at Florida State University (1949-1976) with two later decades at the University of Houston. In collaboration with Houston Grand Opera, he and David Gockley co-founded the Houston Grand Opera Studio, a young artist program that has mentored generations of singers, conductors, directors, and composers. After such a Promethean career, the impetus toward retirement pulled Floyd back to family and friends in Tallahassee in 1996.

Floyd’s substantial nonoperatic catalog embraces small- and large-scale song and choral cycles, a singularly challenging piano sonata, books of etudes, and several symphonic movements. Among his many awards and honors, a Guggenheim Fellowship in 1956 and a Ford Foundation grant in 1959 subsidized the protracted and painful births of The Passion of Jonathan Wade and Of Mice and Men. The Metropolitan Opera National Company inaugurated its debut season with Susannah in 1965, and the parent company performed the work at Lincoln Center in 1999.

In 2001, Floyd was inducted into the American Academy of Arts and Letters, followed in 2004 by his reception of the National Medal of Arts. In 2008, in the company of Leontyne Price, he became one of the first recipients of the National Endowment for the Arts Opera Honors awards. Upon receiving his NEA Opera Honor, Floyd reflected on his lifelong pursuit of writing theater-driven operas that could appeal to new and wider audiences. “You don’t have to pander to an audience, but I think you have the give them what perhaps they would expect and respond to, and then more,” said Floyd in an interview at the time. “When we look back on the 18th century, the Viennese public got what they needed from Mozart, but they had no idea what else he was giving them. And I think that is as great a contribution as a composer can make.”

This article was published in the Winter 2022 issue of Opera America Magazine.

Thomas Holliday

Thomas Holliday is the author of the biography Falling Up: The Days and Nights of Carlisle Floyd, written at the composer’s invitation.