An Oral History with Ben Krywosz

On January 31st, 2020, producer, director, and dramaturg Ben Krywosz sat down with OPERA America's President/CEO Marc A. Scorca for a conversation about opera and their life.

This interview was originally recorded on January 31st, 2020.

The Oral History Project is supported by the Arthur F. and Alice E. Adams Charitable Foundation.

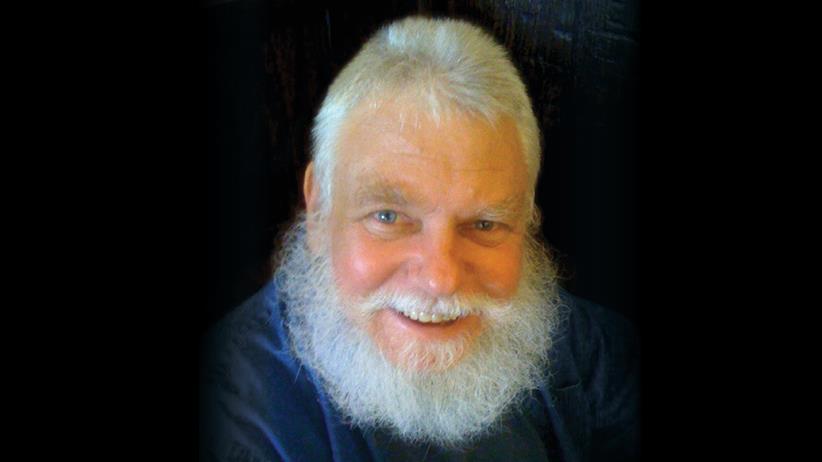

Ben Krywosz, artistic director

Ben Krywosz is the artistic director and co-founder of St. Paul’s Nautilus Music-Theater, formed in 1986 to present new American opera and music theater. He oversaw OPERA America’s first grant program for new works, Opera for the 80s and Beyond, which awarded $2.3 million to opera companies from 1983 to 1990.

Oral History Project

Discover the full collection of oral histories at the link below.

Transcript

Marc A. Scorca: This is all part of our oral history project, and we are working to interview 50 people who just really reach back deeply into American opera, OPERA America's history. Just to try to get a picture of what it was like and how far we've come, what the journey has been, where we need to go still. So this isn't just to reminisce about some of the old boys of the board, but just to get a sense of the time. But first, Ben, how did you find opera, or how did opera find you?

Ben Krywosz: Well, I actually got my start in this field doing psychedelic light shows in the San Francisco Bay area, and I started that when I was in high school in 1967. And I'm embarrassed to admit to this day, I have never done psychedelic drugs. It just wasn't part of my construct. But what I was interested in at the time was the music that played such an important part. This is in the San Francisco Bay area, so it was all of that cultural context, a time and place for ferment, to say the least. And I was very interested in the visual images in relationship to the music and words. And there was also a part of me that was interested in the technical aspects of how you would get a projector and what you would do to make images. And so there was that balancing between the technical and the artistic. At the time, and it's hard to realize this now as I speak to younger people, the information was not available. There was no internet. We had to make things up. A lot of experimentation in my mother's garage. (With) a colleague of mine, the two of us formed a little company and we tried a bunch of different things and that's how you learn what works and what doesn't work. We established a light show company. We did light shows at rock and roll dances throughout the late '60's, going to the early '70's. And then we separated away from that world and started doing our own concerts. And I graduated from high school in 1969 and wanted to major in light shows. That was going to be my career direction. There was something about that form that intrigued me. But it turns out that even in San Francisco in 1970, you couldn't major in light shows. But I did find in San Francisco State - there was a very good film school there, and they had an individual major option, which nobody had taken advantage of. I went to the Dean of the Creative Arts and I said, "You've got this clause in your catalog about creating an individual major, and I'd like to do that". And he said, "Well, I will be your advisor on that". He called me the vanguard of the future. It was the first independent major that they had, and when I eventually graduated (because I was going part time) there were a number of people who were doing that. But in the course of putting together that major, it really required me to look at a number of different fields, pull together fields and so forth. And, of course, music and theater were the major ones. And in the course of that, I started studying classical music. We had already started using avant-garde jazz and classical music in our light concerts, as we were doing our own concerts at the time, and stumbled upon Wagner. And it was a very coincidental thing. In terms of the larger social context - I had no idea about what opera really was. I had a lot of preconceptions about it, of course. And I had started going to musical theater, the San Francisco Civic Light Opera and the touring shows and so forth. So I had a sense of that. But one day I received in the mail from the Time Life magazine books, an opportunity to purchase a recording of this thing called the Ring Cycle. And I still have the brochure: it was a big envelope and it had very interesting pictures on the front, and inside there was some discussion about what the Ring was. And it had this piece of plastic that was about six inches square and you punch a hole in the middle and you'd put it on your record player. And there it was. I just put it on, it was this [singing a Ring motif], and then the voice comes in, "Deep within the Rhine river", and the narrations are going...and it instantly grabbed me. I thought, "What the heck is this?" And all of the pictures were basically the new Bayreuth kind of approach, plus Arthur Rackham drawings and so forth. And I thought, "Well, this is really interesting. I should know more about this". It had some resonance and I wasn't quite sure what it was. A couple of days later, out of the blue, I saw an article in the San Francisco Chronicle that the San Francisco Opera Company was doing the Ring Cycle that fall. And I thought, "Oh, well I should go see this. I should get these recordings". They were offering basically the Solti recordings, the first stereo recording and the most recent recording of the Ring complete, along with some books and so forth. And you'd subscribe to it, and every month they would send you one of the operas and all that. So I thought, "Well I'll do that. And then this fall, I'll go see the opera. I mean, getting a ticket should be no problem. Who goes to the opera nowadays?" So I ordered the recordings and I called the San Francisco Opera box office and said, "I'd like to buy a ticket for the Ring cycle". And the guy just laughed. And I said, "What's so funny?" And he said, "Well, we've been sold out for well over a year". I thought, "Huh, okay. Well, all right, I really want to see this. How can I do this?" And he said, "You can go standing room". I said, "Great, how do I do that?" "Well, you come about six o'clock and then you wait in line, and then when they open the doors, you get your ticket and you go in". I said, "Okay, all great, so I'll be there at six o'clock in the evening". He said, "No, no, no, six o'clock in the morning". And I said, "What?" He said, "Yeah. People start lining up at six o'clock in the morning". This is San Francisco Opera, the War Memorial Opera House. And I had gone to the Symphony there, but I had never been to the Opera. So I knew the Opera House. And I thought, "Well, okay, I guess I'll do that". Which I did. So my first opera was the Ring Cycle. I stood through it, because there were no tickets available. And eventually I became seduced by live performance. The following spring...at the time Kurt Herbert Adler was the general director and it really turned San Francisco into an opera-heavy city. He had the fall season; he had Spring Opera Theater, which was opera in English, very theatrically oriented at the Curran Theatre.

Marc A. Scorca: Spring Opera was in English?

Ben Krywosz: Everything was in English. It was in a smaller theater; Broadway house - the Curran Theater. Very theatrical. It was intended to appeal to a different audience than the fall season, which was of course international opera. So the Ring Cycle was in the fall of '72, and in the spring of '73, I got tickets to the Spring Opera Theater and was introduced to Carmen, which was a very powerful production. A beautiful, gorgeous production of St. Matthew Passion, with a Ming Cho Lee set and Gerald Freedman directed it. And The Grand Duchess Gerolstein, which was absolutely hilarious. I had never thought I'd laugh so much at a live performance. And then there was a fourth piece on the program that I could not find anything out about; there was no information. In those days you're gonna need to go to the library. You go to the Reader's Guide to Periodical Literature. There was nothing on this thing called Postcard from Morocco. I thought, "Well, I guess I'll just go see what it is". And I was transfixed. It was The Minnesota Opera on tour. Wesley Balk had directed. Philip Brunelle was conducting; there was The Minnesota Opera ensemble. And I was so intrigued that I actually went back a second time to see it, even though I didn't have a ticket, and I got there just in time as it was starting. And I just walked into the theater; nobody took my ticket and there were empty seats, and so I was able to see it a second time and I thought, "Well, this is something worth pursuing. I need to be more aware of this". And so I really started to get into opera, while I was doing my individual major. And ultimately since I was doing part time - I graduated I think in '76 - I had developed a project within the intermedia independent major. And they gave me a degree. I mean, I had developed all sorts of ideas about how media - different levels of intermedia, mixed media and so forth, and created basically a thought project because I didn't have the technology at the time to do it. Now it could be done very easily, but at the time it was this live performance with the orchestra and visuals and so forth. And the panel that looked at it all just said, "Well, you seem to know what you're doing". And they gave me my degree. But by then I had really been seduced by live performance and became a regular subscriber of the opera company starting in '74, and really started to devote myself to opera. And finally made a commitment in '76/'77, and formed a little company called West Coast Opera Service. It was not a production company, but I made multimedia education kits for teachers who were teaching opera. I started doing a series of previews for the San Francisco Opera and a number of places around the San Francisco Bay area, where I basically give lectures and that's how I would learn the repertory. And I also started a newsletter called Opera Calendar. And it was basically just a listing of all the opera activity on the west coast. And I would write to opera companies and say, send me your brochure. And then every three months, I would print this little calendar and I had a couple of hundred subscribers for $3 each or whatever.

Marc A. Scorca: Let's pause there for a second, because here you are tracking opera activity in the 1970's. And I don't want to suggest that in 1970 when you began college, that you realized that Glynn Ross had sarted OPERA America up in Seattle. So I'll let that go. But here you are tracking performances in the mid 1970's in San Francisco. So what was on the programs? You mentioned Postcard from Morocco at the Spring Opera Theater. Were these other ensembles, these other companies doing American opera? Were they just doing 19th century opera? What was going on?

Ben Krywosz: Well my focus with the Opera Calendar, which was a device to find out what was going on, and to track what was going on - and to make me "press," which then allowed me to get comps to everything that I wanted to go to - that was a conscious choice for how do I learn the repertory? And so therefore, if somebody was doing a production of Tosca somewhere, I would study the recording and then go to the production and they'd give you tickets and so forth. And I didn't really focus on contemporary work. Most of the companies on the west coast at the time were smaller companies obviously: either university academic endeavors or small companies like West Bay Opera, Scholar Opera in Palo Alto. In fact, I remember as I was putting all this together, I thought, "I see there's a Seattle Opera and there's the San Francisco Opera, the San Diego Opera. There must be a Los Angeles Opera". So I remember actually calling directory assistance and asking for the number of the Los Angeles Opera. And she said, "It's not here". I said, "Well, do you have like Opera LA or Opera...? And she couldn't find anything. I thought, "That's weird". And eventually I found, of course, that City Opera was touring. And in those days travel was pretty easy. So actually, I started going to these other companies. It would be possible on a Sunday morning to grab a flight down to San Diego for $25 from San Francisco, and see a matinee performance, and then fly back back home that evening. And I did that with LA, (when I) went to see City Opera. Most of this was standard rep. And in fact, I started tracking the Seattle production of the Ring Cycle, which San Diego was doing on a yearly basis. And ultimately I went up to Seattle and did the whole cycle during one of the weeks. They did it in English. And they did it in German. But for the most part it was standard rep, 'cause that's what I was learning. But I was drawn to contemporary work, and most of the contemporary work that was being done was by smaller companies, or academic institutions. There wasn't a whole lot going on. In '76 was the bicentennial commissions. San Francisco Opera did Angle of Repose by Andrew Imbrie. And then City Opera would usually have one or two contemporary American operas when they toured to LA. But for the most part, anything that was new or contemporary was done by the smaller companies. At the same time, I was becoming more aware of the alternative theater world, which was pretty active in San Francisco at the time. And that was truly left of center aesthetically. It didn't have a direct connection to the opera world, but of course, ultimately played a role in all of this.

Marc A. Scorca: So you joined OPERA America in '84, I think it was, because of OPERA America's newfound commitment to supporting the creation and production of new opera. And if we look back in our own literature, even an article that you wrote for one of our publications in 1983, there were four premieres of works by OPERA America member companies. So new opera wasn't unheard of, but it was rare.

Ben Krywosz: That was one of the sources of friction between those within the professional opera field and outside of the opera field. Because the premise of Opera for the '80's and Beyond was that new opera was endangered, new opera was not being written. And I thought that was the case. It seemed logical to me. Once I got into the program and started researching, I realized opera was alive and well, and opera was being created all over the place. It just wasn't being done by the membership of OPERA America. And at that time, the OPERA America membership - it really was a membership organization - was very insular. It supported its members really well, but it didn't look outside of the field very much. That's certainly one of the radical changes that happened certainly under your leadership and over the course of the last 30 years - a real opening up. And so when people say, "Well, there aren't any new operas being written", well actually there are a lot of operas being written, but they're being done by smaller companies, by academic institutions and by individual artists and other arts institutions that are not aesthetically compatible with the way that most conventional opera companies, that we think of as professional opera companies. So one of the challenges of the form was how to bring that together. And one of the ways was to bring those artists into the opera companies. And another way was to expand the opera companies to include that world. And both of those things I think have contributed to a shift in the situation that we're in now.

Marc A. Scorca: I'm so glad you lay it out that way, because certainly if we look back, there were very few new operas being done by the established opera companies, but if you get deeper into the literature, there was a new work stream going on. Perhaps not as robust as it is today, but nonetheless, new work was being created. Now you did a tour around the country and I remember when you visited me, 1984/85 to talk about what we were doing. But nonetheless, you wanted to help companies get over the issues they had, the perceived barriers they had around producing new work. Again, as you say, to bring the flow of creativity into the established opera company environment. What was put out to you as the issues around producing new work?

Ben Krywosz: Well, I think there were the overt issues and then there were the - sort of the explicit issues and the implicit issues. And the explicit issues had 'we don't have enough money'. And it was too big of a risk, and we would endanger our company, and our audiences are conservative, and so forth. So all those kinds of excuses that were clearly laid out. And of course the program tried to address that by providing money. And in some instances that was sufficient to get somebody...if somebody was genuinely interested, but really felt like they needed to reduce the risk. And that was one of the challenges. I remember having a long conversation with John Ludwig about this (at) the National Opera Institute, later the National Institute for Music Theater. And he said, "You're never going to reduce the risk. The risk is always going to be there. What you need to do is get people comfortable with the risk, and making sure that they are willing to do whatever's necessary to make it happen", which makes sense to me. And so that was one of the things that the program was able to do, was actually provide financial support, and therefore increase people's comfort level with taking the risk. The other thing that became clear early on, and this was something that the advisory council talked about, and became really clear in conversations with the major figures in the opera field, is that there was a high level of ignorance about contemporary work in general - contemporary art as well as contemporary music, contemporary theater especially. And so therefore, there was a lack of awareness. And I mean that just descriptively. People were focused on their company working with 18th and 19th century European repertoire. That was their mission. And so therefore it didn't occur to them, or behoove them to stay abreast of contemporary aesthetic adventures. And that had been true for a long time. And in talking with a lot of these general directors, and watching the works that began to emerge, it was clear that they were rooted in a very old model of how to tell stories to music. And when you look at the arc of aesthetic development, the aesthetic explorations of the 20th century in theater had not yet trickled down to the people in the opera field. So the notion of how to tell a story was still rooted in the naturalism of the first half of the 20th century. And the effort to make opera more relevant, to use that word, usually meant we need to be more theatrical. We needed to compete with film and television. There was a fear that people were going to leave the theater and go to the movie theaters or go to watch things at home on the television. And now of course we have the internet. And so therefore we had to compete on their terms. And so a general aesthetic emerged of naturalism. This is the way we tell stories. And in order to make it more engaging to an audience, we need to be more like film. We need to tell those stories naturalistically. The notion that we had to be more theatrical meant that performers would study acting. And in fact there's a limit to what we think of as American naturalistic acting and its application to opera. It was a challenge trying to sort through that lack of awareness that things had changed aesthetically in the performing arts. And so one of the early initiatives...the intent was, we needed to educate the field. And the challenge with that, of course, was that the field didn't particularly want to be educated, or didn't feel the need to be educated. And so that was one of the dynamics that we were dealing with early on...just acknowledging that we need to bring people up to speed. We had a number of initiatives. We did a series of newsletters, the Opera for the '80's and Beyond Newsletters that we did, where we sent those out. And this was designed very specifically. Basically we were saying, "Here's people you should be aware of". And the first one was Leonard Bernstein. People would say, "Oh yeah, we know about Leonard Bernstein". And then Stephen Sondheim. "Oh yeah, I've heard of him, I guess. Yeah, he worked with Bernstein". And then also Meredith Monk. "Who?" "Well Meredith Monk." Simply by positioning those three together, people started to get a sense of, "Oh, there's something else going on" and this newsletter continued I think for three or four years of just every month sending some information. Here's somebody you should be aware of. And for those who are interested, they had access to information that they might not have had before. We also at some point began publishing these information memos. Every month we'd be sending out...Here's something going on you should be aware of...Check out this TV special...In your town this is happening, or, You might want to come to New York...Get an exploration fellowship from the program, come and see it, meet the artists. And those went out on a pretty regular basis, usually every couple of weeks.

Marc A. Scorca: I remember getting these and reading these, and I loved that they were three hole punched, so you could actually put them in a notebook.

Ben Krywosz: Well we had a binder. There was a red binder, and somewhere in your archives you should have a copy of that. And so the idea was that a general director, or in some instances more likely their staff, would be able to track these things. We did a program, it's a little bit of controversy around a multimedia program that we did...it was my first conference, which would have been January of 1985. And it was a major performance essentially - a live performance, plus a lot of slide projection, video and so forth. Eric Salzman and I worked together. I brought in Karen Miller to help put it all together. We had a cast of eight or whatever. It was a whole premise that Tim Jerome was a performer, who presented himself as a professor. And this was many years in the future, and they had just discovered this trove of archival material dating back to the late 1900's, where there was the beginnings of the resurgence of opera in America, and so forth. And they found all this documentary material. And so therefore it would go through all of these excerpts, dating back to The Disappointment, Evangeline, 1878, all the way up through the 20th century: Postcard from Morocco, Meredith Monk, West Side Story, Robert Ashley, Laurie Anderson, Gospel at Colonus, Sunday in the Park with George, that sort of thing. And it was just this massive event. We held it in - OPERA America was in Washington DC at the time and we held it out at a school in Maryland, Silver Spring, maybe it was. But in any case, it was an educational effort at the annual conference.

Marc A. Scorca: You said in an article that you wrote for us a long time ago, that creating new work is a completely different activity that was not particularly compatible with the production process of most opera companies. And you've been speaking about the fact that the opera company staff, opera company leaders in those years are not aware of the composers, librettists who are doing new opera, not necessarily aware of the style of contemporary theater and how the works could be made more theatrical, not by amplifying 19th century realism, but by creating something new. But here you mention the production process of most opera companies was not compatible with doing new work. What did you mean by that?

Ben Krywosz: Well (with) the traditional production process, people begin by knowing the score. And they know what we're going to do. We know Carmen, what it is, and then you go into the casting, who's the cast going to be. Plan that three or four years in advance, depending upon the size of the company, of course. And the international houses, even more than that and some of the smaller houses, less than that. But you plan ahead, and then you've got your director who has a concept, and you work with the designer. All that goes. And at no point are you ever in conversation with the composer and the librettist, since the work is already done, and presumably they're dead. I do remember getting a call from a project. I had kind of brokered a composer and a writer to make a piece for a company. They were finally proceeding on it. It was headed toward production and they were in production. I got a call frantically from the general director who said, "We've got some real problems here. I need some help figuring this out". And I said, "What's the problem?" And he said, "Well, the composer wants to be in rehearsal". I said, "Yeah". "Well, we've never had that before". "Of course you haven't". And the idea that a composer would have opinions about the production is something that had not been experienced. And eventually I did come to the conclusion (and this was from my own work as a director and as a producer at Minnesota), that a world premier production that did not honor the initial vision of the composer and the writer was going to be problematic, because the composer and the writer would feel that their production had not yet been premiered. And so it really required an inclusion of the composer and the writer to different levels of degree, depending upon the personalities, but an inclusion of them in the developmental process and the production process as much as possible. And to allow for a timeline that was very different than: we begin with what the piece is, and we develop the production based on that. Versus, we begin with the people. They're going to create something. We're not sure what it is yet. Let's see how it goes. And we need to have the flexibility institutionally that we may need to change the cast. We may need to change the production concept. The issue of the venue may be problematic. And as the piece develops, those things will become clear. And if our timeline is so long, the practicalities of making that happen become less. The model that was referred to so often was the notion of trying to shift direction of the ocean liner. When some organization is so large that they really can't easily shift, how do you get the nimbleness that's required to develop new work? - which people who develop new work know about. But if that's new to you, that's part of the learning process certainly.

Marc A. Scorca: It's also the case that companies plan opening nights on a certain date, and sometimes the new work isn't ready by that date and the nimbleness to say, "Okay, it's not going to be in the opening slot this season. It will be in the opening slot next season". It's a real challenge for companies that were accustomed to announcing their repertoire, casting their repertoire three or four years in advance.

Ben Krywosz: Well, the other thing that comes into play with that is that if your company is established as 'this is the way we do things, and we have an orchestra that we have a contract with; we have a chorus we have a contract with; we have different departments that know how they're going raise money, how they're going to market this, how they're going to go through the production process'. And then to have a piece that doesn't fit into that model is a real challenge. And so oftentimes the solidity of a company is such that the new work has to adapt to the company, rather than the company adapt to the new work. And so then you get a piece that may not require a full orchestra but will be given a full orchestra, 'cause we have these people, why not use them, which then will tend oftentimes to say the opera company is looking for a composer. They begin with (needing) a composer that knows how to write for an orchestra. So we begin with that. And so then you turn to the orchestral field where you're dealing with composers who write music rather than composers who write music for the theater, who are willing and interested in telling stories through music. And I think that those are two very different sensibilities. Now, obviously it's not black and white and there's the shades of gradation that make it a little more flexible, but still in general, we don't listen to Brahms operas; we don't listen to Puccini string quartets. So why would you turn to an orchestral composer who works with color and harmony so much, when you're dealing with a form where melody and rhythm is the driving force because it comes from the performer's throat or their heartbeat. So those are all questions that come into play when you're dealing with the aesthetics of the piece, let alone the actual logistical aspects of getting a piece mounted.

Marc A. Scorca: The term music theater came into being, and certainly when the National Endowment for the Arts set up its own opera program, it was called the Opera Music Theater program. And that's I guess 1979. And the National Opera Institute eventually became the National Institute of Music Theater and we were clear in Opera for the '80's and Beyond that we supported the creation and production of opera and music theater works. So did you observe the invention of this double noun term music theater? Was it something that you had already encountered when you were in California in the mid 1970's, this concept of music theater? What did the term mean then?

Ben Krywosz: Yes I had encountered it, and it was something, especially in the world of alternative work, alternative theater work, that music theater was thought of as this hybrid term that was not quite opera, although it used some of the tools of opera; wasn't a musical, because the term musical theater has certain connotations for people as does the word opera. But it was an attempt to kind of take a larger view of it. And it had been around for decades. It's not that it was brand new and invented in the '70's. So there's a whole history and you can date it back to the Gertrude Stein, Virgil Thomson works if you want. But certainly through the experiments and the 'humanistic operas', in quotes, written by Menotti and Bernstein and Mark Blitzstein and Kurt Weill, all of that a real attempt at American opera. That would be the first wave as it were. But it was a controversial term. And when the OMT program was started, there was a lot of conversation around this. And there was a move afoot to call it music theater, and the opera people did not want to lose the term opera. The musical theater people wanted to hold on to musical theater as they know it.

Marc A. Scorca: So there was never a thought that it would just be the Opera Program. There was a possibility it might've just been the Music Theater program.

Ben Krywosz: Well that was discussed, and because these two forces came together, the musical theater people that were stuck in the theater program, and the opera people that were stuck in the music program, it really was a coming together. So it wasn't just the opera people who were trying to establish the OMT program, musical theater people are an important part of it. And ultimately they went through negotiations and I'm told that it was the opera hyphen musical theater, not music theater, but opera hyphen musical theater. They didn't want to slash because that would separate the two, and they were trying to bring it together. And this was people like Beverly Sills and Hal Prince, and Wesley was involved in it, and Bob Darling and all of these folks who were trying to recognize that there was something that the opera world and the musical theater world have in common. And they weren't able to completely articulate it, but they recognized that there was a connection there and that connection needed to be honored. Janet Brenner, who was the associate director of the program, actually wrote a history of the development of the OMT program. I have a copy of that paper somewhere. I thought I'd maybe given it to you, or maybe given it to Laura Lee (Everett) that really laid out the various lobbying efforts to make that program happen. And ultimately it did happen. And they had the good luck, I guess foresight, I'm not quite sure, but they went through a series of visionary program directors starting with Jim Ireland, Ed Korn, and then, of course, Ann Farris and Patrick Smith, and they're the ones that invited people into that program that had nowhere else to go. People who were not doing operas; people that were not doing musical theater. And that's where you started having a home for artists like Meredith Monk or George Coates or Robert Wilson, Philip Glass and all of that. And that turned that spectrum of opera musical theater into opera musical theater alternative works - that became a triangle. And many of us who were involved at the time later in the '80's really began to see that as one of the strengths of this particular initiative was to make that happen. And I served as the chair of the New American Works panel, which was one program of the OMT program. And to have in the same room people who were unaware of these other genres really led to a lot of interaction and a lot of support for all of that. And so it was a real tragedy to have lost that program that really had it continued, we'd be much further along now than we are.

Marc A. Scorca: The National Opera Institute, which no longer exists, it had changed its name in the '80's to the National Institute of Music Theater and it closed at the very end of 1989. But NOI predated OPERA America. And you certainly had contact, close relations with John Ludwig, who was the director of it. What was NOI? What did it do?

Ben Krywosz: Well it supported opera, but especially it seemed its focus was on new work and contemporary work and developing artists. So I actually, from '81 to '83, was on a National Opera Institute fellowship. I got a directing fellowship and apprenticeship to work with Wesley. And they had already established that program a number of years earlier, and I had been aware of it, but I didn't have necessarily an opportunity to take advantage of it until I met Wesley and he invited me to come out to Minnesota to be his assistant, and we were able to get to the NOI directors of the apprenticeship program to support that. And it really, it gave fellowships to many different artists working in the field and really developed... They had conductor fellowships and composer and writer...

Marc A. Scorca: ...stage director and some administrative ones as well.

Ben Krywosz: Administrative ones. And, they did showcases of developing new work, as well as they still had connections with the conventional, traditional opera field.

Marc A. Scorca: But it was not a membership organization the way that OPERA America was a membership organization.

Ben Krywosz: It was a different kind of service organization. John had been the general manager of The Minnesota Opera, back in the early days when it first got started, back in the early '60's, when it was still a program at the Walker Art Center. And then eventually he went on to San Francisco Opera and was the manager at San Francisco Opera under Kurt Herbert Adler. And I'm not quite sure how the NOI got started and how John got involved with them, but they were a major force in the field. Marianne Harding, who later became my associate here at OPERA America came from them. So she brought in all of that knowledge, which was really useful. It's one of those issues that the consolidation of the field, the pluses and minuses. When you've got various organizations, it's one thing to coordinate. It's one thing not to coordinate, and it's something else to merge. So Central Opera Service was the same kind of situation, that the NOI and the Central Opera Service and for that matter the National Opera Association, with the academic world, to have these various elements. I feel like you can look back and say, well, they were laying the groundwork, the foundation for OPERA America's growth. OPERA America was a separate organization at the time, but I don't think that OPERA America would have blossomed like it has, if it hadn't been for those other organizations too.

Marc A. Scorca: I agree completely.

Ben Krywosz: The whole process would have been much, much slower if it happened at all. So I think that some of the impulses of the NOI of 'NIMT' as we ended up calling it, I would love to see. We've talked about the issue of the apprenticeship and how practical that was. It was a function of trusting that this young person who seemed to have some potential for making a contribution to the field, could be nurtured by assigning them to a mentor for a year or two. I had two years with Wesley. For those two years, to learn at the feet of a master, and knowing that that was not an arbitrary choice. That Wesley and I were compatible and that other people would choose other directors, whose work they knew. I'd like to direct like that or I'd like to conduct in this style or I would like to develop this approach for whatever. I think that's important. I think that that sense of apprenticeship is something that is too easily lost if we turn everything over to the academic world.

Marc A. Scorca: You have mentioned Wesley Balk a number of times, and I never had the pleasure of knowing him. I'd love to hear you just recount a little bit about Wesley.

Ben Krywosz: Well, he was a character, as so many people in our field are. He's oftentimes known as the guy who taught opera singers how to act. And of course it's way more complicated than that, and he stands on the shoulders of giants as we all do. But he really began to explore the whole idea of what do we mean when we say we want performers to be dramatically credible, or to act natural, or to do whatever it is that we want them to do when we see a fabulous performer production. We know that something is happening there. And he had a very analytical mind, and was able to break things down in a way that allowed you to see the individual parts of the singing-acting process, and to put them in perspective to other parts. He developed the whole idea - his first book was called The Complete Singer Actor - where he recognized, "Here's what I'm going for. I'm not quite sure how to get there just yet". And he really took a look at sort of the arc of the history of the art form, the relationship between music and theater, and laid it out geographically of these countries, and in between, there was this border area that was in dispute. And so he laid it all out in a very kind of charming and funny sort of way. But really questioned, how does this work? What are we talking about? And he had a whole series of exercises where he was beginning to explore working with performers, a lot of improv stuff, a lot of stuff working with separating what the tools are for the singer-actor. In his second book, he got more specific. This was called Performing Power. And it actually came out of a Ford Foundation study that was done in the early '80's. And that actually has a direct connection to me getting the job at OPERA America. And that is the Ford Foundation was interested in serving the professional opera companies that belonged to OPERA America, who had training programs for singer actors. And ultimately they engaged Bob Darling and Richard Rodzinski to do this survey. They went around to all these various opera companies and interviewed anybody that had a young artist program at the time, which was relatively new. And actually it was The Minnesota Opera - Wesley had started the first year round or nine month resident artists - The Minnesota Opera Studio back in the late '70's. And when the Ford Foundation was putting together this initiative, Ed Korn came to me. He had just taken over at The Minnesota Opera and he said that there was some discussion of having me do that survey, but the feeling was that I was just young enough, and just starting out and therefore probably not quite right for this project. However, he said, "There's an initiative brewing that you would probably be appropriate for. So let's just keep in touch". And ultimately he's the one that suggested that I apply for the Opera for the '80's and Beyond position, and apparently had touted me to the powers that be, and that ultimately is how that happened. So Richard and Robert went around and told these opera companies, and interviewed all the young artists. And the one comment that kept coming up time and time again was that these performers said, "This program is robbing me of my performing power". And that's one of the reasons why Wesley called his second book Performing Power, where he really established the three external tools (of) the singer-actor: the voice, the face and the body. And that was radical in the theater world because the theater world does not make a distinction between the face and the body. That's all the physical and the vocal is something separate. But in fact, he really identified the face as a separate communicative tool. And then in his third book, The Radiant Performer, he took those three external tools and connected them to the internal tools, which is the mind and the emotions, and developed this chart of this relationship between the various things and how they interfere with each other, and how they support each other. So really breaking that down in a very specific way, really helped performers start to identify, "Oh yes, so why do my eyebrows go up when I hit a high note? That takes away my ability to look angry if I'm singing a rage aria" and so forth. That's just a minor example, but that really takes a look at that whole integrated approach to singing, acting. And his fourth book that was privately published, was a Traveler's Guide to A Radiant Performance, where he again went back to he geographic model of these countries, and laid it out as if it were literally a traveler's guide. And how do you develop exercises and tools to reinforce the relationship between the host and how to break the unhealthy relationships between those tools.

Marc A. Scorca: Was Wesley Balk involved in the original Center Opera?

Ben Krywosz: He came in, I believe in the second year. The opera company was started at the Walker Arts Center when they had built the Guthrie Theater and the Guthrie was only a residence in the summer months. So then they had this beautiful big theater for the fall and winter and spring. And so Martin Friedman connected with the local company that was doing amateur opera and Dominick Argento had just arrived at the University of Minnesota. And so they started developing the Center Opera Company. And they brought in John Ludwig early on - I don't know exactly when - to be the general manager. And then John brought in Wesley because they had gone to school together at Yale. And so I believe he came in the second year, if I remember correctly. And was there for 20 years.

Marc A. Scorca: You mentioned Ed Korn. And I haven't asked anyone about Ed. So when I graduated from college, my first job was working for Ed at what was then the Opera Company of Philadelphia, because they had joined together the Grand Opera and the Lyric Opera into this new company called Opera Company of Philadelphia. Then I think Ed was the first general director of that new merged company. And he was there for a few years, maybe three, before then going on to the NEA to head up the Opera Music Theater Program where he was for a few years before he went to Minnesota.

Ben Krywosz: He was also at Wolf Trap somewhere in there.

Marc A. Scorca: I'm not aware of that. He went to Philadelphia from The Metropolitan Opera.

Ben Krywosz: That vaguely rings a bell.

Marc A. Scorca: So a real character, and a real believer and a real character.

Ben Krywosz: He was very supportive of so many artists. A volatile personality at times. Reminded me a lot of Kurt Herbert Adler in that respect, who he also worked for. He was in San Francisco too.

Marc A. Scorca: I think he went from San Francisco to The Met, The Met to Philadelphia.

Ben Krywosz: Oh, that could be.

Marc A. Scorca: I just haven't thought about Ed in a long time. Okay, so here we are: 2020. 50 years after you began at college, and you were just discovering opera. Opera was discovering itself, or the confluence of the new opera movement was just beginning to discover the established opera companies. So as you think about where we've come, are you encouraged, discouraged, pleased? How do you react to where we are today?

Ben Krywosz: Well, I have mixed feelings, as you might imagine. I am amazed at times to come to the New Works Forum or the Annual Conference, or to read that some opera company, somewhere in the United States is doing a world premier. And I just think back 30 years ago, 35 years ago - well, that just would've been impossible and unthinkable back in the early days of opera. I think a lot of people who are present and working today simply have no idea what it was like back then. I mean the lack of interest and at times even animosity toward new work was really intense. I think in those days we were really - there's many of us, certainly myself and Marieanne and many people that were on the advisory council, who really felt that this was such an important thing to pursue. We used to joke, taking a line from the Blues Brothers, 'we were on a mission from God'. That somehow we needed to make this big oil tanker shift a little bit in direction if not turn around. And so there was a lot of passion and the kind of passion that comes from a sense of, if not injustice, a sense of missed opportunity. And so we were pretty intent on making the change. Now when I see the change that has happened, it's very gratifying, and it's remarkable to think about. Occasionally I'll run into somebody from those days. Michael Korie and I were talking, because we go way back in that respect. I had a wonderful lunch two years ago with Ellen Blassingham out in Seattle. And thinking back to the days when we were fighting the good fight. And to see how things are today, it is really remarkable. There's a much wider acceptance of the notion of new work. There's a recognition that if we don't get on board with new work, our opportunities for growth are going to be limited. And that seems to be a given. I mean oftentimes, I'll say the question that used to be asked at annual conferences was, "Why should we do a new work?" And now the question is, "What new work are we doing?" And so that's great and that's really wonderful to see. And, at the same time, certainly with the demise of the OMT program, there's been a slowing down, it seems, of the embracing of what this form is. And I do feel that opera as an art form - if we want to use that term opera, I use the term music theater because it's more inclusive of many different stylistic approaches - but I do believe that we're headed toward the development of a new American opera. And I don't think ultimately in most people's view, the term opera is going to be used. But we are talking about telling stories to music. And I think that the opera field has the potential to embrace that and become a major player in that movement. And I'm concerned that many of the works that are being created now don't contribute to that. And I think part of it is a stylistic issue, and part of it is an aesthetic issue. There's a cultural issue and a sense of - we talk about opera being elitist, and so many of us argue that it's not, and yet it's still presented that way in many respects - that the costs associated with making a new work oftentimes are unwarranted, and it's not necessary to commission a new work for $100,000 and do a $2 million production. Because the reality is that in any art form, most of the work that's generated at any given moment is not going to match the standards that you have, that has evolved over the course of time. And I used to say that to opera company general directors, that if you're doing new works, you better get used to the idea that most of the work that you do, is not going to be very good, based on your standards of what you consider to be good work.

Marc A. Scorca: But even historically, the churn rate is unbelievable in the decade of Mozart and the decades of Rossini, the failure to success rate is vast.

Ben Krywosz: And so you've got to get comfortable with that, and you've got to have a different reason for doing new work, than quality, than contributing to the cannon. You have to position the work differently than to say, we're going to do, Aida, Bohème, Carmen and a new work. Because if you do those four as part of your season, then the perception is that that new work, of course isn't going to be as good as the others, and chances are numerically speaking, probably not. And so how do you shift the thinking so that creative producers become creative producers and not just producers? And how do you tap into the energy of this form that is already being accomplished by other people, who are not in the professional opera field? That's the thing where I see the missed opportunity. And I think that in terms of what we're talking about - toward a new American opera - is not the heritage of European based opera or the development of American musical theater. But it's this triangle and what's happening in the middle. And without getting into definitions, I can argue that Hamilton is the great American opera and that Susannah or Of Mice and Men - fabulous pieces - but they are important steps toward that. Guys and Dolls was an important step toward that. Even Einstein on the Beach was an important step toward that. But that's an example of a piece of that deals both with musical complexity, verbal dexterity, and the nonlinear dramaturgy that people are getting more comfortable with. So we're not there yet, but we're developing something that I think at some point in the future we can say, this is America's contribution to world music theater. In the same way that opera was Europe's response to that impulse.

Marc A. Scorca: You've said that one of the greatest handicaps we have in opera is the lack of good librettists. And I'd like to hear from you what you think makes a good librettist. What makes a good libretto?

Ben Krywosz: A libretto is not the text. A libretto is the shape of the piece. It's the architecture, the structure of it. Most of the time, that structure is clarified through the text. And you have to actually have words, but you look at a Meredith Monk piece or a Robert Ashley piece, in that the text itself is not the crucial element. It's the overall structure of the piece. And I think that when playwrights - and I work a lot with playwrights - when they come in to write a libretto, they think, "I guess I just have to have fewer words and the lines need to be shorter and terser. And I guess that's the difference between a libretto and a play". And I tell them, "No, that's not it at all". It really is a function of trying to discover what are the strengths of this form and how do you create an architecture or a skeleton, whatever metaphor you want to use, that will take advantage of that form and do something that other art forms can't do. When we did this little thing a couple of weeks ago on adaptation, for instance, we broke up into different groups - and a number of the groups chose the Brett Kavanaugh story to tell. I don't know if you heard about this. And there were six different approaches. And it's like, "Obviously this is the topic that's on people's minds". But then each of the treatments made it very clear that none of them were going to tell the story, as we know the story. None of them were going to do a documentary, naturalistic telling of the story. There was the sense of the fantastical, the sense of the spiritual, the sense of the emotional, and a way of taking that source material and saying, "We know the basics of this story. Now we're going to explore what are the elements that this art form can do that a documentary or film isn't going to do or a play isn't going to do". And I think that a libretto will take advantage of that. If all the libretto is, is a play that is sung instead of spoken, then you have not taken advantage of the form. So, it's not just a function of shorter phrases or less words. The other thing that I think a good libretto does, and most contemporary opera librettos don't, is the musicality of the language. Which is not just the function of what does this sound like, but what is the meter and rhythm of the language. And the meter and rhythm of the language is a gift to the composer, who can then more easily write using melody and rhythm, which I maintain are the primary tools of the opera composer, not harmony and color. And lately I've been saying somewhat facetiously (and yet there's an element of truth) that the librettist's job is to ensure that the composer writes as little music as possible.

Marc A. Scorca: Say that again.

Ben Krywosz: The librettist's job is to ensure that the composer writes as little music as possible. And what I mean by that, is that if they're writing in meter that allows the composer to use material and repeat material and perhaps alter the material, but work within this very specific musical world. If the libretto is in prose, they have to write new music all the time. And no wonder people think it takes two or three years to write an opera. We know that that's not true. We know that if there is a standard language that a composer is using, and there's a high level of skill and the resources are there, you can write an opera very quickly. That one can be more responsive than most companies are. But again, if you've got a company where you're planning four years in advance, then you're sort of stuck in that model. But I think a good libretto written in verse allows the composer to repeat material, to alter existing material, and not have to generate new stuff all the time.

Marc A. Scorca: You've mentioned Wesley Balk, clearly a mentor. Are there other mentors in your life?

Ben Krywosz: Well, yeah, I can think of a couple, and in different capacities. Peter Meckel, who runs Hidden Valley Music Seminars out in California was my first real professional contact with the field, and we're still good friends and I usually see him every year or so when I go out to California. And he's taught me a lot about institutional administration and the nimbleness and flexibility that's required, and taking a look at, how does one accomplish what one wants to do, using limited resources and how flexibility and nimbleness is an important part of that. Lawrence Halprin, a landscape architect. We did this creativity workshop that we did at OPERA America that was done at one of the annual conferences, and looking at the relationship of his work to his life and the sense of integration of working from a responsive point of view. He'd worked a lot with groups that he would create in response to groups, and doing surveys and explorations of what is it that a group needs. And if you were going to design a park, what does that mean and how do we go about doing that? Gosh, I feel like I'm leaving people off, and if this ever goes on the record I'm going to invariably alienate people - I've worked with so many good people. Certainly, Bob Darling has been a wonderful colleague and somebody who has influenced my thinking over the years. Howard Klein, who was with the Rockefeller Foundation and having a lot of conversations with him. He taught me how to treat people, and taught me about elegance. That may not be apparent, but I think in terms of how does one interact with people. Somebody of his social and financial stature, that was really powerful. There are a number of people. I'm at a loss. It's one of those things: you have a thousand examples and somebody asks for one and then suddenly you're stuck as to what to say.

Marc A. Scorca: What advice do you give young people who want to advance their careers, want to make an impact on opera with new work?

Ben Krywosz: I guess I would go back to the question that I was asking people...You mentioned I was touring around. Well I did many tours. I went around the country a number of times to meet with people in different iterations or meetings and follow-ups and encouraging, trying to develop those relationships to persuade and move people. And in many of those meetings I would ask them about doing a new work and that's where we'd get into this whole idea that I would like to do newer pieces, but just don't have the money. And after a while I realized that really we're dealing with a much larger issue. And so the question that I started asking then, and still ask to this day, especially with the younger people I work with is: what are you trying to accomplish with your life, and why have you chosen opera to do that? And to try to make a connection between one's life's work, one's heart's desire, and this particular form. There are many ways to live a good life. What does it mean to live a good life, and how is this art form going to help with that? And so I encourage them to ask that question, and to answer that question for themselves. And I certainly encourage younger people to take a look at not just what they are doing, and what they want to do, and what others are doing and what others want to do, but build on what has happened in the past. This is one of my reasons for archiving, for understanding what's come before. It's one of the ways that I encourage - I'm doing composer studio right now, and dealing with some people that don't know about the repertoire. I was dealing with one composer who doesn't listen to opera. I said, "You've got to listen to opera. You don't have to like it, that's not the issue. But if you don't know how Verdi, Puccini, Mozart, Wagner worked, then you're cutting yourself off. And why would you throw that out the window?" And one composer said, "Well I can't listen to Wagner, I'm Jewish". I said, "So here's the thing. We know that he was an anti-Semite, and we know his music was appropriated by the Nazis. Yes, all that is true. If you don't figure out how he did what he did musically, artistically, then he and the others will have won. So learn how to do that, and do it better than he did. And don't let your preconceptions about the larger social issues, which are real and need to be acknowledged, but they can also be set aside in favor of personal and artistic growth". And so I think building on the past is just as important as heading toward the future. This is where we're headed, so we obviously we're not downplaying that, but we're just saying that if you build, then you're going to get to where you want to be sooner, quicker, more effectively, it seems to me.

Marc A. Scorca: Love those words. And a slightly different trajectory here. So I know that at Nautilus you're working on organizational transition, and we have awarded a grant, because I think it's such an important question you're asking about how do you either continue an organization that is founder-led after the founder has transitioned into retirement? Or how do you ask the question: does this organization declare victory and close? So how is that exploration going?

Ben Krywosz: I don't think there was ever any sense that we're going to declare victory. We may at some point say "We've done a good job, and we're going to stop now". Although that's just one of many possible outcomes. It's going very well. It's going a little bit slower than I would have liked, only because I'm continuing to do the work at the same time that I'm examining the work. And it would be a whole lot easier if I just stopped doing the work and just examined it. So that slows us down a little bit, but I've got two colleagues who are really focused on it, and they keep pushing me along, and I keep dragging them back, and they keep pushing me along - so we have a nice dynamic about that. I just, two days ago, got an email with a proposed survey...we're going to be dealing with the audience and other stakeholders. We went ahead and did our major survey for the artists we've worked with. We opened that up for three weeks last May, and all the material came in. Over the summer that was sort of consolidated, and in the fall our consultant began examining it and in November, she gave me a preliminary report of just the numbers - she hadn't gone into the actual material yet. I think she got it down to 469 surveys, to go through. She said there's a high level of consistency. She did a two page summary of everything, of where she is right now. And 95% of the people are saying this made a substantial impact on their artistic growth and their career choices. She did say that in her first review of the anecdotal and qualitative responses that there was a high level of consistency. So it's going really, really well. I can say it's plodding along a little slower, and we've got the time. I'm starting this at a time where I'm still active and engaged, and have the energy to do it. It's hard for me to imagine that I'm going to be 70 in two years. That just does not compute at all. I don't feel that way. And yet it's true. And so I am trying to be realistic about all of this. Once that transition happens in whatever way that it does, how might I still make a contribution to the field? My interest hasn't lessened at all. My engagement with the mechanics of how to keep a company going, that has reduced. I'm tired of asking for money. I'm tired of trying to deal with the logistics sometimes of all of that. But that doesn't mean that I don't have anything else to offer.

Marc A. Scorca: I should say. You are our go-to person for insight and such articulate explanations of your core values. And I just find it inspiring. It is why you are always a featured speaker at our New Works Forum and our annual conferences. You have so much to say it and say it so beautifully. So I just want to thank you for taking time once again out of your schedule to allow me to at least capture a couple of snapshots in the last 50 years through your eyes. I'm tremendously grateful.

Ben Krywosz: Well, I'm happy to do it. Of course. I am still on a mission from God...

Marc A. Scorca: Absolutely. Oh, keep going. Keep going. Thank you, Ben.