The Oral History Project

We continue our series of excerpts from OPERA America’s Oral History Project — an initiative to record the recollections of key figures who have shaped American opera over the past 50 years. New oral histories will be released periodically through early 2023 at operaamerica.org/OralHistory.

The Oral History Project is supported by the Arthur F. and Alice E. Adams Charitable Foundation.

Denyce Graves

Denyce Graves is a mezzo-soprano, cultural ambassador, and voice instructor. She made her stage directing debut this year with Carmen at Minnesota Opera and The Glimmerglass Festival.

Her first opera

“When I was 13 years old, and a student at the Duke Ellington High School in Washington D.C., we were taken to the final dress rehearsal of Beethoven’s Fidelio at Washington Opera. We had the opportunity to go behind the scenes and meet the artists, and that was incredibly imprinting. But for me, it was listening to a recording of Leontyne Price that really seared into me a love of opera and pointed me in the direction I’ve taken in life.”

Church songs

“I grew up in the church, going seven days a week, and other kids teased us for having to do that. But in that teeny little Pentecostal church we used to belong to, all these songs were being poured into me. I had no idea that was going to give me my life and inform every piece of music that I pick up to this day. That became the foundation on which I built my career.”

Her Carmen breakthrough

“The first Carmen I did, in 1991 with Minnesota Opera, was my first real big opportunity. Keith Warner did this new avant-garde telling of the story. Stephen O’Mara was my Don José, and Elizabeth Knighton Printy was the Micaëla — spectacular artists who were engaged singing actors. Because of the work that we did together, and my colleagues who also lifted me up, my managers and people in the industry could see me not only as a singer, but a stage animal. And I began to be offered roles that were really meaty acting parts.”

The Denyce Graves Foundation

“The Denyce Graves Foundation was born out of me wanting to help my students and find a way to empower them. And then I learned about this incredible woman, Mary Cardwell Dawson [founder of the National Negro Opera Company], and discovered in our research about her that there were so many others like her — like Sissieretta Jones, who decided 20 years after being a slave that she wanted to be an opera singer. We might know Lily Pons, Enrico Caruso, and Maria Callas, but we don’t know some of these other wonderful, great artists. And so the foundation is sitting at the intersection of social justice, American history, and vocal artists. We’re supporting and telling the stories of artists from the past, present, and future.”

Michael Ching

Michael Ching is a composer, librettist, conductor, and songwriter. He is composer in residence at the Savannah VOICE Festival and previously served as artistic and general director of Opera Memphis (1992–2010) and as music director of both Nickel City Opera (2012–2017) and Amarillo Opera (2016–2020).

Studying with Carlisle Floyd at Houston Grand Opera Studio

“My year with Carlisle [from 1980–1981] was very, very challenging. He basically wouldn’t let me write a note of music, and we really concentrated on libretto writing and creating good outlines. He would see me at a lesson and say, ‘Well, Michael, this is riddled with clichés. Don’t you think you can do better than that?’ It was very hard on my ego, but great training. I will say that my work may not be brilliant, but it always works, and I owe much of that to Carlisle.”

Sequels to the canon

“I learned from what I consider to be the best — the Marriage of Figaros, the Carmens, the Butterflies. The idea for Buoso’s Ghost [my sequel to Gianni Schicci] came about during joint auditions in New York in the mid-1990s. It was Willie Anthony Waters of Miami Opera, Linda Jackson of Chautauqua Opera, myself, and a few other people. We were sitting around just shooting the breeze about what happens to Madam Butterfly’s kid, or what happens to the Germont family. Do they actually speak after Violetta dies? Do they kiss and make up? And so, Buoso’s Ghost developed as a result of a breakfast conversation speculating on opera.”

Comic operas

“In a comic opera, the lyrics just need to come through 90 to 95 percent. In a tragic opera, it’s possible to get away with 40, 50, or 60 percent comprehension in the audience. But jokes are so quick that you really need almost full comprehension. And that means writing a fundamentally different style of music than, say, large orchestral forces. So, it just has different challenges.”

Joseph Volpe

Beginning in 1964, Joseph Volpe served in various capacities at the Metropolitan Opera, finishing with his tenure as general manager from 1990 to 2006. He is currently executive director of the Sarasota Ballet.

The “Old” Met

“It was a thrill to be there. I’ve seen many theaters in my career now, but the old Met was a very special place, and that’s why there was great resistance to it being torn down. But the atmosphere, just the smell — you were in a different world when you went into the Met at 39th Street.”

Working with performers

“Dealing with personnel issues probably was the most difficult [part of the job]. Believe it or not, the easiest part for me was dealing with the performers. Mirella Freni would talk to me like I was her brother. I wasn’t prepared for that, but it was one of the best parts of being the general manager. There are general managers that have no relationship with the performers, but that was not me.”

Rudolf Bing, general manager of the Met (1950–1972)

“Rudolf Bing would mentor me. We were in Atlanta for my first tour with the company, in 1967, and his assistant came over at the end of the performance and said, ‘Mr. Bing wishes to see you in the morning at 10 o’clock.’ So we discussed my job, and then he said to me, ‘Well, how did Franco Corelli behave last night backstage?’ I said, ‘I’m sorry, Mr. Bing, I wasn’t paying attention.’ He said, ‘I’m going to give you a piece of advice: Pay attention to everything from now on, because that’s what this company is about. And you will learn if you pay attention.’”

Herbert von Karajan

“When we did Karajan’s Ring, I must have spent a month in Salzburg every time they opened one of the operas. To watch him work, not as a conductor, but just his involvement — upstage, he’s up on apparatus to do flying; he’s here, he’s there. He was really hands-on, incredible in a sense.”

Proudest moments

“I’m proud of what we did with expanding the repertoire — the world premieres and Met premieres. I’m particularly proud of the relationship I had with singers when they had difficulties, because I can recall many incidences where a soprano was having trouble with a director and stormed off the stage at a rehearsal and said, ‘I’m not going on; I’m not going to work with him.’ And I was able to convince both parties to understand the pressures and issues that the other party was having. It’s always nice to hear from a fabulous singer, ‘Oh, I love you; you saved my life.’

Harolyn Blackwell

Soprano Harolyn Blackwell has sung roles like Lucia di Lammermoor, Gilda in Rigolettoand Marie in La fille du régimentwith the world’s leading opera companies. She currently teaches voice at Manhattan School of Music, NYU Steinhardt, and Barnard College.

Discovering her voice

“My fourth-grade teacher was the first person to plant the seed that I was born to sing. I was a very shy child, and she helped me discover Harolyn the person and Harolyn the voice. I was always a child who said, ‘I can’t,’ and one day at a lesson, she said to me, ‘Can’t is not a word in our vocabulary,’ and I have taken that with me from nine years of age to today.”

Broadway debut in 1980

“It was my first Broadway audition, and I thought, ‘What are my chances of getting West Side Story on Broadway, on my first audition?’ But I felt, I’ll do this audition and learn something from it, and if I don’t get it, that’s fine. Well, I was fortunate, and they called me to understudy the role of Maria and to sing ‘Somewhere.’”

Musical theater versus opera

“I have always felt that whatever repertoire I sing, I need to have a good vocal technique, and that’s what I tell my students. The style changes — singing musical theater is totally different than singing the style of opera — but the basic technique of how to take a good breath and project the voice doesn’t change across the board.”

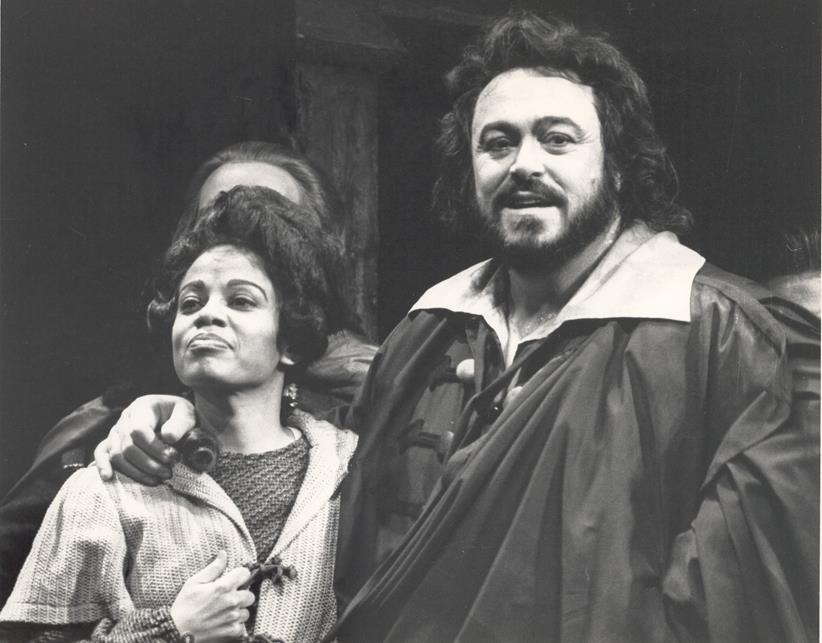

Working with Pavarotti

“It was a lesson every night being on stage with him. I learned so much about the voice, where to place the text, the phrasing, the style. I remember my first time working with him. I was in Chicago, and it was the final dress rehearsal [of Un ballo in maschera]. I was kneeling at his feet when he began to sing, and I thought: ‘Oh my God, this is the most beautiful voice I have ever heard in my life.’ The sound surrounded me to the point where I missed my entrance, and I heard the conductor go, ‘Oscar, Oscar, you’re late.’”

Practice and patience

“I tell my students that [this career] is a process, and it never stops. You will take four steps forward and then four steps backward. But I always had this goal of where I wanted to go, and I knew I would get there if I was willing to do the work. I remember one day when I was doing La fille, a journalist asked me, ‘So where does your success come from, Harolyn?’ Out of nowhere, I said, ‘My four Ps: patience, practice, perseverance, and prayers.’”

Peter Sellars

Stage director Peter Sellars has gained international renown for his groundbreaking productions at companies including Dutch National Opera, English National Opera, Lyric Opera of Chicago, Opéra national de Paris, Salzburg Festival, and San Francisco Opera.

First records

“I first heard opera on records. I imagined these incredible things from the early records that I had, like Thomas Beecham’s version of Abduction from the Seraglio, and I was staging it all in my mind. When I finally got to an opera, it was a little boring by comparison. But later, when I was going to school in Massachusetts, Sarah Caldwell was making these incredible, crazy productions [at Opera Company of Boston]. And so early on, the repertoire I was exposed to was very progressive and revolutionary. She was the first person in the U.S. to do Les Troyens, Nono’s Intolleranza, Lulu...”

A unique Ring cycle in 1978

“I used to work in the summer at a children’s theater in Denver, Colorado — the Elitch Theater for Children. We were three blocks from what was billed as the largest Woolworth’s in the world, and so we thought we had to do something grand for this situation. I suggested we do the Ring cycle [with puppets]. The rainbow bridge came out of the fourth-floor men’s room of an adjacent office building. We set downtown Denver alive, and people came from all over to see this Ring cycle in the streets.”

From Handel to Adams

“Staging 18th-century operas was foundational work that made [John Adams and Alice Goodman’s] Nixon in China make sense, because I was doing Handel’s Julius Caesar in Egypt at the same time. What happens when a Western leader visits the Middle East? So, from Julius Caesar in Egypt to Nixon in China was not a big step. And of course, Handel’s gift was to make these things very amusing, very strange, very delicious, and devastating and profound.”

Mozart’s relevance

“Mozart of course lived in a period of great social upheaval and unbelievable violence. And so his big project is forgiveness. How do we reach across the lines? How do we acknowledge abuses and move forward and actually forgive each other? Mozart wrote the soundtrack for forgiveness.”

Opera’s power

“Opera is where all the art forms meet. It’s a logical meeting place for working with painters, architects, great writers, musicians, and dancers. Opera is a place that is so deep for what it means to be alive and be human, and at the same time, be trying to touch the edges of infinity and the universe.”

This article was published in the Fall 2022 issue of Opera America Magazine.