Equity at Center Stage

The racial justice movement of 2020 has provoked an industry-wide assessment of equity, diversity, and inclusion policies.

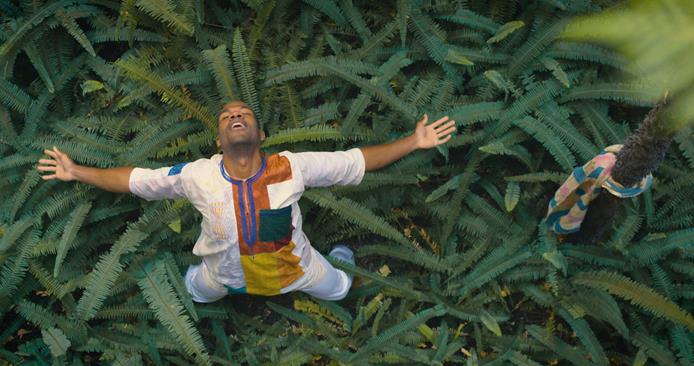

Toronto’s Against the Grain Theatre has a tradition of offering innovative theatrical stagings of Handel’s Messiah each holiday season. But its 2020 production was perhaps its most significant departure from tradition yet. Like so many pandemic-era productions, it streamed as an online video piece. But its most unusual aspect was the way Against the Grain tailored the Messiah to respond to our historical moment. Messiah/Complex, co-directed by Reneltta Arluk and ATG Artistic Director Joel Ivany, featured 12 soloists of color. Members of the multicultural ensemble translated the oratorio’s biblical text into Arabic, French, and Indigenous Canadian languages.

Messiah/Complex was in its planning stages on May 25, the day George Floyd was murdered, and during the subsequent Black Lives Matter protests. Those events had a decisive influence on ATG’s bold approach. “We wanted to see change within our company, and one way we could do that was by casting the entire production with Indigenous and Black people, and other people of color,” says Ivany. In one of the production’s most expressly political interpretations, Black mezzo-soprano Catherine Daniel performed “Why Do the Nations So Furiously Rage Together?” while walking through Toronto’s Graffiti Alley, a walkway transformed by street artists into a memorial for black victims of police violence.

The racial justice protests of 2020 have been felt in innumerable areas of American life, opera included. In their immediate wake, opera companies released a slew of statements avowing their commitments to racial equity. But in the months since, companies have faced the more complicated task of following through on those ideals. The work has taken many forms, from repertory choices and production decisions, to internal equity planning and the development of new fellowships and employment opportunities specifically for opera professionals of color.

The Black Opera Alliance, an organization made up of Black opera professionals, grew out of the BLM movement. The group was founded by bass-baritone Derrell Acon, director of engagement and equity at Long Beach Opera, and it hopes to hold the industry accountable to the anti-racist ideals of last spring. “We have two very specific goals,” says Acon “The first is community healing and fellowship. The second is outward-facing, watchdog-type action.”

“There are all of these racial justice, EDI roundtables and panels and conversations, where Black people and other marginalized groups are expressing these pains as a way for white people to understand better, to become more sympathetic, and to maybe change,” Acon says. “But rarely is the conversation centered in, ‘How do we substantively build the system in order to make sure that a better diversity of voices is introduced into the uppermost folds of leadership in the industry?’”

The group made its presence felt quickly. After David Tucker, a board member of the Richard Tucker Music Foundation and the son of Richard Tucker himself, had posted racist comments on soprano Julia Bullock’s Facebook page, BOA published an open letter in protest. Within two days, Tucker was removed from the foundation’s board. Then in September, BOA released its eight-point “Pledge for Racial Equity and Systemic Change in Opera,” with the aim of providing a framework for racial justice within the industry (see “A Framework for Change").

The BOA pledge is collecting signatories among American opera companies. Portland Opera has been one of the first. “We signed it as-is,” says General Director Sue Dixon. “We should be able to do all of the things that they’re asking for. It may not be in the next year or two, but we’re going to work really hard to make sure that all of these bullet points are in some way achievable.” After working with equity consultants, Portland Opera has assembled a staff and board committee and is currently drafting a “cultural equity plan.”

Opera Philadelphia is another company that has assembled an equity and inclusion committee, after bringing in equity consultants to conduct an analysis of the company’s operations. The idea, says committee member Derren Mangum, OP’s director of institutional giving, is to “help us set some benchmarks and understand what we really need to be focused on.” Since the summer, the committee has met nearly weekly and has hosted monthly all-staff meetings on topics like micro-aggressions and unconscious bias.

With its Cardwell-Dawson Resident Artist Program (a recipient of an OA Innovation Grant), Washington D.C.’s IN Series has become the first U.S. company to launch a residency program solely for artists of color. The program was conceived before 2020’s racial justice uprising, and originally Timothy Nelson, IN Series’ artistic director, was in charge of its design. But the pandemic delayed its launch, and then the BLM movement changed its very shape. “Floyd’s murder and the protest focused the whole conversation,” says Nelson. “I realized that as a white male, I’m not the right person to be planning this.” As a result, IN Series opted to have the four resident artists themselves, working with a group of outside arts leaders, design the contours of the program.

Cardwell-Dawson is not a standard young artist program. The participants are already engaged in the field as performers and activists. The program, instead of offering training, provides resources for their professional development. “For white singers, there’s a real pipeline from a performing career to being the head, whether executive or artistic, of a company,” says Nelson. “I would say that most of the leadership of America’s opera companies are former singers, and most of them are white, and most of them are male. That pipeline doesn’t seem to exist for singers of color. We can create a space where artists can tell us about their larger interests, and hopefully nurture the next generation of leaders.”

Opera Theatre of Saint Louis’ new Clayco Future Leaders Fellowship grew out of staff brainstorming sessions in the wake of George Floyd’s murder. Created to serve emerging arts administrators, the program draws its participants from historically underrepresented communities. The fellows will work full-time in either the advancement, marketing, or artistic departments at OTSL, while also gaining exposure to the full range of company operations.

“Our crews, backstage teams, and administrative staff are still overwhelmingly white,” says Andrew Jorgensen, OTSL’s general director. “That’s not a recipe for what success looks like in the future. You can’t authentically serve a community that is more than 40 percent Black when your staff and company don’t look like that and don’t have those lived experiences.”

OTSL has also replaced its planned spring production of Porgy and Bess with Highway 1, U.S.A. by William Grant Still and Verna Arvey. “Porgy is incredibly problematic,” says Jorgensen. “As the Black Lives Matter movement came to the fore last summer, it became immediately clear to me that this was not the moment to tell a story by white creators about Black people in caricatured form.”

Floyd was killed in Minneapolis, which made his death a matter of local impact for Minnesota Opera. In the immediate aftermath of the 2020 BLM uprisings, the company’s staff spent a day of service in the community, with some staff members attending a protest, while others helped damaged local businesses or brought donations to communities in which essential businesses had closed. Since then, the company has released a series of four eight- to ten-minute digital operas, called “MNiatures,” created largely by people of color that includes Kashimana Ahua and Khary Jackson’s Don’t Tread on Me: A Century of Racism. At its February virtual benefit, the company debuted Art Is a Verb by B.E. Boykin and Harrison David Rivers, with a passage about the Floyd murder. (“Is there a more accurate picture/Of how Black people are treated in America/Than a white man with a knee on his neck?”)

Fort Worth Opera’s “A Night of Black Excellence,” a streaming gala with an entirely Black roster of performers, was conceived in the wake of the summer’s racial justice movement. The concert was the brainchild of FWO’s recently appointed general director, Afton Battle: the first Black person and first woman to hold that position. “It was celebrating Black arts and culture and history,” Battle says. “The murders of George Floyd, Breonna Taylor, and Ahmaud Arbery are part of this history now, and ‘A Night of Black Excellence’ was most definitely in response to that. The response from the community was one of ‘Finally! We want this, we need this as way of healing and representation.’”

“Some folks felt it was exclusionary and racist,” Battle says of the concert. “But this industry and this company have neglected to celebrate the Black community. I thought, ‘We can do this to uplift this community.’” The concert was one night only — but this is ongoing work.”

One prominent response to the BLM movement has come from New York City’s Heartbeat Opera. Breathing Free, a visual album that debuted in February, features a majority-Black cast in excerpts from Fidelio alongside Negro spirituals and works by Black composers. Acon is among the performers featured in the work, and much of the behind-the-scenes talent is also Black.

“There’s a graphic where it shows all of the participants on that project, and it’s just amazing to see that about 60 percent if not more of them are Black,” says Acon. “Those are not the demographics of that opera company, so that took some real intentional work. They made sure that this was really a Black project. That kind of intentionality is what I want to see industry-wide.”

A Framework for Change

The Black Opera Alliance’s “Pledge for Racial Equity and Systemic Change in Opera”

This article was published in the Spring 2021 issue of Opera America Magazine.

Gabrielle Bruney

Gabrielle Bruney is a New York-based arts and culture writer whose work has appeared in Esquire, Vice, and Jezebel.